Responses to the Problem of Juvenile Runaways

Your analysis of your local problem should give you a better understanding of the factors contributing to it. Once you have analyzed your local problem and established a baseline for measuring effectiveness, you should consider possible responses to address the problem.

The following response strategies provide a foundation of ideas for addressing your particular problem. These strategies are drawn from a variety of research studies and police reports. Several of these strategies may apply to your community's problem. It is critical that you tailor responses to local circumstances, and that you can justify each response based on reliable analysis. In most cases, an effective strategy will involve implementing several different responses. Law enforcement responses alone are seldom effective in reducing or solving the problem. Do not limit yourself to considering what police can do: carefully consider whether others in your community share responsibility for the problem and can help police better respond to it.

General Considerations for an Effective Response Strategy

Although more likely to focus on minimizing the harms that come to or are caused by runaways while they are absent from home, police can also be effective advocates in efforts to address the reasons juveniles run away (e.g., physical and sexual abuse) and to improve the quality of services designed to respond to juveniles upon their return (e.g., family mediation and preservation). Most researchers and practitioners agree that social service providers, rather than police, are primarily responsible for addressing this issue. Therefore, part of the police response may be to shift responsibility to other agencies better equipped to render services to runaways and their families.§

§ Refer to Response Guide No. 3, Shifting and Sharing Responsibility for Public Safety Problems for more information.

That said, police have a legitimate role in locating juveniles reported missing and in ensuring runaways' safety when they spend time on the street.[66] Police receive missing persons reports from parents, foster care providers, and group home staff. Further, their 24-hour street presence means they are most likely to encounter runaways, whether reported missing or not. Police should partner with other agencies to address the issue effectively, and a variety of agency-level responses will be required.

Agency-Level Responses

1. Appointing a local runaway coordinator. Given the overlap in responsibility between the police department and social service providers, some state and local jurisdictions have found it helpful to appoint a runaway coordinator. The coordinator convenes interagency meetings, plans and coordinates services, manages service delivery contracts, and monitors outcomes. Although they may or may not craft formal interagency protocols, the coordinators build bridges for these agreements to evolve.§ The Phoenix Police Department and the Tumbleweed Center initiated an outreach program designed to reduce police time spent managing runaways and to provide immediate and long-term assistance to runaways. When police come in contact with runaways, they connect with Tumbleweed staff using a crisis line, pager, or special police radio call received by staff monitoring the radio channel. Tumbleweed staff meet juveniles at the precinct and provide emergency shelter, transportation home, and follow-up services with the family. See http://www.tumbleweed.org and Posner (1994) for more information.

§§ See Posner (1994) for a more complete discussion of the many forms, benefits, and considerations for police-social service collaborations.

These agreements should be formalized into memorandums of understanding between police and social service agencies. In addition to specific protocols for transporting youth and providing services, these agreements can also create specific protections for confidentiality and privacy, when appropriate. Formalizing these agreements will also promote sustainability so the interagency relationships and protocols are not dependent on the individuals who created them.

3. Developing joint protocols with foster care providers and group homes. Those providing substitute care are sometimes quick to contact police when juveniles have not returned to the facility by a specified time.§§§ Many times, juveniles are simply late, rather than missing. Further, staff may not assess juveniles' level of risk before identifying the event as an emergency. To avoid overwhelming police resources, some jurisdictions use protocols specifying a threshold for police contact when juveniles do not return to the facility as expected (e.g., call police only after midnight, only when juveniles have left the center without permission, or only after staff have failed to locate the juveniles). The protocol should categorize the various types of absences and state required procedures for each situation.[67] The circumstances surrounding the absences should be monitored and re-categorized as necessary.§§§ Through an analysis of calls-for-service data, the Fresno Police Department found that 40 substitute care providers made a total of 1,024 calls in a single year. Five providers were responsible for 50 percent of the calls. Joint protocols and training from centers who manage juveniles' absences without police contact were employed to reduce the high utilization rates of the five providers (Fresno Police Department 1996).

Linking foster care providers and group home staff with community police officers also has benefits: [68]

- Police get to know the juveniles informally and may have more leverage in discouraging them from running away.

- Police develop a greater appreciation for the types of problems juveniles and staff face.

- Police respond to requests for assistance more consistently and follow up more meaningfully.

- Reasons why juveniles run away from home and substitute care

- Police investigative techniques and available tools

- Child abuse reporting laws

- Policies surrounding confidentiality

- Situations when secure detention may be required to protect the juveniles from harm

- Juvenile-centered treatment philosophy and advocacy

- Locally available resources and services

- Procedures for interagency communication.

§ Adapted from Florida Department of Law Enforcement and Florida Department of Children & Families (2002).

5. Sharing information. Agencies must share relevant information about the juveniles, precipitating factors, associates, and companions for an effective response. Interagency agreements should specify the types of information needed to ensure the safety of juveniles who have run away and should develop procedures for efficient interagency communication.These interagency agreements can be difficult to negotiate when agency partners have different confidentiality standards.Parents are important partners in information sharing. They have the right to access information that agency staff may not be able to obtain. Some jurisdictions obtain parents' written consent to access records from schools, social services, and other agencies.§

§ Takas and Bass (1996) provide a sample parental consent form that features clear, simple language and specifies the types of records police may use. Police should work with local agencies to ensure the form meets their requirements for accessing information. Guidelines for approaching agency staff to request information are also provided.

6. Assessing risk. If the primary role of police is to reduce the harm that comes to or is caused by runaways, they need a reliable way to assess the risks facing juveniles who are absent from home or substitute care. Cases should not be classified based solely on age or where the juvenile stays, but rather using a set of locally defined conditions that, when met, will trigger a priority police response. Common risk factors include:§§§§ Refer to National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (2005) for a sample policy incorporating these risk factors.

- Ages 13 and younger. Children ages 13 and younger have less sophisticated decision-making skills and cannot protect themselves from exploitation and older juveniles.[69]

- Out of safety zone for age, physical, or mental condition. This zone will vary depending on the juveniles' characteristics. Juveniles with cognitive impairments may have difficulty communicating their needs and providing information required to access help. They are particularly at risk of exploitation.

- Alcohol or drug dependent. Substance use compromises judgment and the ability to protect oneself from harm.

- At risk of foul play or sexual exploitation. The risk level will depend on the types of illegal activity occurring in the community, where the juveniles are believed to be staying, and the juveniles' past experiences and maturity level.

- Believed to be in life-threatening situation. This assessment will vary depending on the places the juveniles frequent and their experiences during past runaway episodes.

- Absent more than 24 hours before reported to police. A delay in reporting may indicate parental neglect, but could simply be a misunderstanding of the law. Many parents believe missing persons reports require a waiting period.

- In the company of dangerous companions. Some juveniles stay with older adults who may exploit their vulnerability; others associate with peers who use drugs or are involved in criminal activity.

- Inconsistent with normal behavior patterns. An out-of-character departure may signal acute distress or the possibility of foul play.

Classifying juveniles accordingly enables police to focus their resources on those juveniles at highest risk of being harmed and those most likely to commit crime while absent from home or care. Agreement from local partners about the types of cases to which police will dedicate resources also helps to promote a positive police image.

Specific Responses to Reduce Juvenile Runaways

The specific responses to juvenile runaways are organized according to time sequence—before the juveniles run away, when the juveniles depart home or care, while the juveniles are absent, and when or if the juveniles return. Many things can be done to address the reasons juveniles run away from home or care, such as offering support and guidance to parents and improving the quality of institutional care. A vast research base details the variety of family counseling, case management, and social work strategies that are effective in preventing runaway episodes, assisting juveniles and families with underlying dysfunction, and easing conflict upon return. These social service-based strategies are not reviewed at length here because police will have little direct involvement in such things.

Before They Run

7. Providing prevention materials when responding to calls for service. Analyzing local call-for-service data may reveal that certain families have high levels of parent-child conflict. Responding officers can provide these families with information on conflict resolution strategies and resources for additional parent and juvenile support.§ Referrals should include parent support services, advice and counseling programs and school-based support for juveniles, and family preservation and mediation services. The officer who responds to missing persons reports can provide similar information, along with guidance to help parents locate their children. Police efforts to generate awareness can be supplemented by school-based information campaigns designed to reach the larger audience of families whose children may run away but for whom police contact is not initiated.§§§ See National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (2004), New York State, Missing and Exploited Children Clearinghouse (2001) for examples of brochures that police could offer when responding to calls for service or to a missing person report. See http://www.ontario.childfind.ca for an additional example. Click "Programs & Services" and then click the "Teen Runaway Prevention Program" link.

§§ The National Runaway Switchboard has developed a prevention curriculum for use in schools that covers coping strategies and a frank discussion of the risks juveniles commonly face when they run away. See www.nrscrisisline.org and click the “Training & Prevention” link. Then click the “Runaway Prevention Curriculum” link to download the full curriculum.

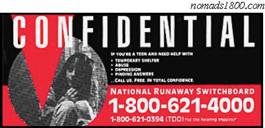

Hotlines refer juveniles to social services to

shield them from the harms involved in living on

the street. If desired, they also help runaways

to contact their parents.

When They Run

9. Using "Missing From Care" forms. When local protocols dictate that juveniles' absences from care should be reported to police (see response No. 3 above), substitute care staff can provide police with information designed to help locate the juveniles and to highlight relevant risk factors. Relevant information includes: [72]- physical description

- recent photograph

- distinguishing marks, tattoos, or piercings

- date and time last seen

- suspected destination and companions

- address of family and other known contacts

- pertinent details from previous runaway episodes

- other relevant risk factors.

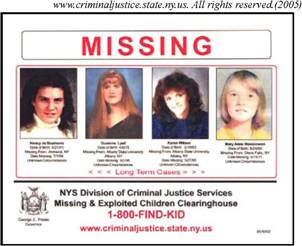

Missing persons posters can help to locate juveniles.

§ See Simons and Willie (2000) and Steidel (2000) for detailed discussions of investigation techniques useful for making this determination.

While They Are Absent From Home or Care

12. Referring juveniles to appropriate social service providers. Police encounter juveniles who have run away from home or care under many conditions. Those living on the street are at particular risk of harm and should be encouraged to access a variety of services to address their immediate and long-term needs. Outreach efforts should inform juveniles about the range of available services, which should include:- Short-term shelter programs that provide safe overnight accommodations

- Drop-in services that provide food, clothing, crisis counseling, and medical attention

- Services that help juveniles contact their parents, if desired

- Counseling services for special issues such as sexual orientation, pregnancy, substance abuse, and mental illness

- Long-term counseling for family mediation and reunification

- Independent living programs for juveniles who cannot return home.

Juveniles who have run away from home or care often do not trust adults and authority figures and are easily deterred from seeking the services they need. Therefore, program credibility is essential and can be enhanced by: [75]

- Involving juveniles in the design and operation of programs

- Ensuring staff honor their commitments to juveniles

- Confronting juveniles with the consequences of running away and challenging them to take responsibility

- Ensuring confidentiality

- Avoiding labeling and blaming juveniles.

§ The Port Authority Police's Youth Services Unit patrols New York City's bus terminal in search of runaways traveling by bus (Elique 1984). The team includes a plainclothes officer is supported by a uniformed officer and a social worker who connect juveniles with a variety of services operated by social services and community-based organizations. In 2004, the Youth Services Unit made over 4,500 contacts with juveniles found loitering in the bus terminal, 225 of whom were determined to be runaways (Port Authority Youth Services Unit 2004). Rather than tying up police time to transport the juvenile, the Youth Services Unit works in cooperation with Childrens Services staff who provide transportation as needed.

§§ The YMCA's Project Safe Place is a national network of businesses and agencies committed to providing a comfortable and secure place for juveniles to make contact with runaway service providers. Juveniles walk into a location displaying the "Safe Place" logo and are immediately put in contact with Safe Place volunteers who come to the location and help juveniles plan their next steps. Nearly 14,000 Safe Place locations nationwide have provided services to nearly 80,000 juveniles since 1983. See http://www.safeplaceservices.org/index.shtml for more information.

15. Using secure placement when appropriate. In a limited number of circumstances, secure placement may be needed to protect juveniles at immediate risk of serious harm. Suicidal juveniles or those engaging in high-risk behaviors (e.g., prostitution, reckless drug use, etc.) may benefit from short-term secure placements until appropriate long-term services can be mobilized. Secure placements can be found in the juvenile justice (e.g., juvenile detention center) and mental health (e.g., hospital) systems and should be extremely time limited.When or If They Return

16. Using transportation aides and free transportation services. Police can conserve valuable time and resources by using civilian volunteers to transport juveniles to runaway shelters and other services. These resources are most useful when volunteers are on call 24 hours a day and when multiple volunteers located throughout the jurisdiction are on call at any given time.[77] A few national airlines and bus companies offer free tickets to runaways from out of state who want to return home but cannot afford to do so.§§ Greyhound's Home Free program operates in partnership with the National Runaway Switchboard. Juveniles access the services by calling the toll-free switchboard, where staff coordinate issuing the ticket.

17. Referring to aftercare services as needed. Despite the likelihood that family problems triggered the runaway episode, most juveniles and families do not use any services when the juveniles return home.[78] When police transport juveniles home or back to care, active referrals for follow-up services can help to resolve family problems and prevent subsequent runaway episodes. Rather than depending on the families to initiate contact, police can submit families' names to a local service provider who makes contact with families and offers services.§§ Parents who receive such contacts often express relief and gratitude for the offer of help.[79]Sample Questions for Follow-Up Interviews with Runaways

- How many times have you run away? (ask for details of events, experiences, interactions, and relationships while absent from home or care)

- What has gone on at home that contributed to your running away?

- Does anyone drink or use drugs?

- Does anyone fight?

- What is a good day for the family? What is a bad day?

- Does anyone ever hurt you? (carefully question about physical and sexual abuse)

- How much control do you or other people have over the things that made you run away? (ask how predictable this type of behavior is, who is responsible for the situation, how changeable those behaviors or events are)

- On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest, how safe is it for you to return home?

- What would have to be different for you to want to stay home? (ask if things have always been this way at home and if not, when they changed and what made them change)

- What would you need to do to make this change happen?

- What would other people have to do to make this change happen?

- How possible are these changes?

- What do you want most for yourself?

- What do you think you need first to get what you want?

- If you were in my place, what is the most important thing to say or do for a juvenile like you?

Adapted from Janus et al. (1987)

Responses With Limited Effectiveness

19. Handling cases over the telephone. An accurate assessment of the risks involved in juveniles' absences is required for a sound response. This assessment is best made in person, where access to juveniles' parents, siblings, and personal effects can help police discover the nuances of each situation.Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Juvenile Runaways

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

- To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

- Your E-mail *

Copy me

- Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.