Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Problems Retaliatory Violent Disputes Page 3

Responses to Retaliatory Violent Disputes

General Considerations for Responding to Retaliatory Disputes

Identifying disputes early provides a basis for preventing the next violent incident from occurring. Preventing retaliatory violence might well require prioritizing the investigation of an incident and arresting one or other of the offenders. But a quick arrest is not always possible and violent events relating to a dispute may continue. Making the prevention of further violence the goal can open a wider range of response strategies than just criminal law enforcement.

Assessing the Risks That Disputes Will Become Violent

Reducing retaliatory violence requires first assessing the risk that disputes will become violent. Some disputes pose higher likelihoods of becoming violent than do others. Before assessing risk, however, you must establish a protocol to determine how and when risk assessments occur.†

† Risk assessment in criminal justice has played a prominent role in a number of areas, including pretrial release, probation and parole. For more on risk assessment and criminal justice see Andrews, Bonta, and Wormith (2006).

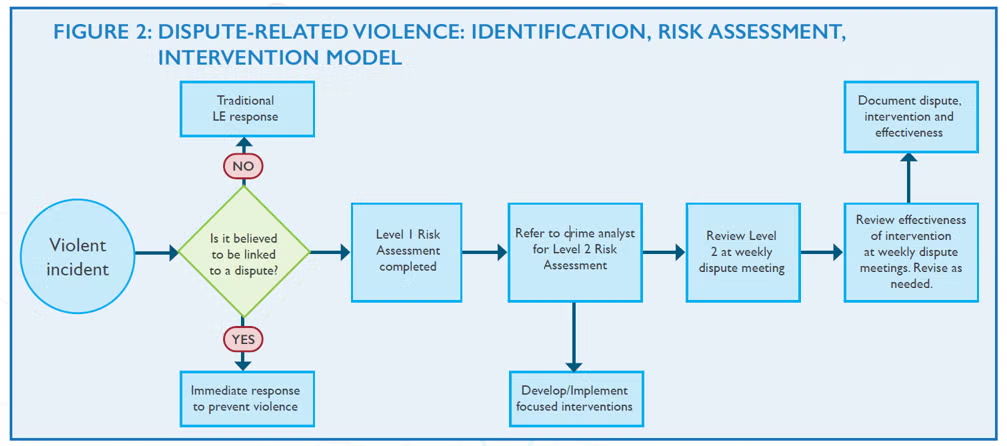

You should establish protocols for when risk assessments are performed. The exact mechanism should consider the unique needs and nature of your police department, but should establish a clear procedure for at least two levels of risk assessment. Any police officer, detective, or analyst who receives credible information about a possible violent retaliatory dispute should complete a level-1 risk assessment form (ideally electronically) documenting the concern, which is quickly routed to a supervisory officer for review. Upon the supervisory officer’s authorization, a level-2 risk assessment should be conducted to gather more thorough information about the history of the dispute and its risks for future violence. See Appendices A and B for sample dispute-risk-assessment forms. A level-1 risk assessment can be conducted either at the discretionary judgment of an officer, detective or analyst, or it can be required whenever certain dispute activities occur (e.g., an assault or shooting, or a credible threat of violence).

A thorough (level 2) violent-retaliatory-dispute risk assessment should consider the following information:

- Violence in the current event

- Linked past violent events

- Involvement of weapons in this dispute

- Participants’ prior violence

- Participants’ reputation for violence

- Participants’ gang, drug, gun, and recent-incarceration history

- Friend or family connections that might instigate violence

- Associates’ gang-, gun-, and drug histories

- Physical proximity of parties’ residences or workplaces

- Other aggravating or mitigating factors

Taking into account the factors above, you need to make two key judgments: First, is the event that caught your attention one of a series of linked violent events suggesting that a dispute is likely to continue, or is it merely a single isolated event? Second, does the incident pose a substantial risk of continuing violence? If you conclude there is a substantial threat of retaliatory violence, you should implement and document preventative strategies.

You should also consider whether the obligation to respond to retaliatory violence will be the responsibility of the entire department or a specialized unit. A department-wide approach makes it possible to leverage all department resources toward reducing retaliatory violence. However, coordination of all departmental resources may be difficult, and competing demands faced by department staff may distract from efforts to focus on retaliatory violence. Designating a specialized unit of officers allows for the sustained prioritization on retaliatory violence. The unit’s success, however, will be contingent upon its cooperation with other sections within the department and with outside agencies. Both of these approaches have been shown to be effective.‡ The option that you choose should depend on your department’s needs.

‡ See El Paso Police Department (2002) and Boston Police Department (2012) Safe Street Teams for examples of programs that designated specialized groups to respond to retaliatory violence. See Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (2008) for a broader approach.

Two types of regular meetings are important for an effective retaliatory-violent-disputes initiative: dispute meetings and incident reviews.

Relevant command staff should discuss at least weekly the status of known violent retaliatory disputes. These dispute meetings provide a forum for intra- and interagency information sharing.56 The meeting should be chaired by police department command staff and include representatives from all local law enforcement agencies, crime analysis centers, community stakeholders, and research partners, if so engaged. The meeting should include reviews of new high-risk disputes, actions taken on existing disputes, and ideas for improving response tactics. A dispute analyst should present case summaries, disputant backgrounds, known vulnerabilities, and assessments of current response tactics.§ These dispute meetings could be integrated into other operational meetings, such as Compstat- style meetings, so long as the focus on disputes, rather than incidents, is not lost.

§ See Gangs Action Group (2011) for an example of the critical role that crime analysts can play in a retaliatory violence intervention.

Conducting formal incident reviews has become an important way of sharing information across agency partners addressing violence problems. They provide a forum for exchanging and analyzing information, and for gaining a shared understanding of cases.57 Incident reviews can provide a foundation for the command reviews, but bear in mind the differences in purpose for these reviews. The goal of dispute meetings is to generate strategies specifically intended to prevent further violence associated with the particular dispute being discussed.

The dispute analyst should develop dispute bulletins to help command staff track violence associated with particular disputes.§§ Dispute bulletins are analyst-generated investigative documents that link incidents believed to be connected to a retaliatory dispute. These bulletins include information about the transgressor and retaliator, and their respective allies, as well as the circumstances of each incident tied to the dispute. Each bulletin should include investigative documentation connecting the incidents. Examining bulletins can help police identify the key characteristics of violent retaliatory disputes and tailor dispute-specific response strategies.

§§ See Appendix C for a sample dispute bulletin.

Once command staff determines that additional follow- up processes are no longer needed, the dispute analyst will complete an assessment of the status of the situation, the impact of any strategies that were implemented and any additional information that came forward in the response to the events. All intervention strategies, responsibilities, and outcomes should be entered into a dispute database. Figure 2 outlines the dispute assessment and intervention process.

Monitoring and Tracking Retaliatory Violent Disputes

You should develop a database to track retaliatory violence and dispute interventions. This database should capture dispute- level processes that are important for understanding the nature of retaliatory violence and how interventions influence outcomes for retaliatory disputes. The database should capture information about field assessments, risk assessments, related cases, amounts and types of violence, and intervention strategies employed. The database should also record activities of police personnel or units that are responsible for addressing the various disputes that are being monitored. Traditional records management systems will provide useful information, but may not adequately capture this information. Ideally, a dedicated dispute-monitoring module would be integrated into the records management system.

The Importance of Strong Leadership and Feedback

Strong leadership is required for a successful retaliatory- violence-intervention project. Leaders must encourage their personnel to think differently about their role in violence reduction. Preventing retaliatory violence relies heavily on patrol officers to collect and forward street intelligence to crime analysts for risk assessment. Command staff must ensure that patrol officers are trained to be recognize, document, and forward such intelligence, and that they receive feedback on both the value of the intelligence they provide and the status of the dispute. Having street intelligence disappear into a virtual black hole is one of the surest ways of discouraging patrol officers from providing it.

Training Line Personnel

It is imperative that your staff are adequately trained to reduce retaliatory violence. Patrol officers should be trained to identify disputes and notify their superiors about them. This training could begin with an introduction to problem-oriented policing and how disputes can be understood as problems that require special police attention. The training could then transition to more specific processes that your department will use to identify, monitor, and respond to retaliatory violence. Additionally, crime analysts will need training on identifying potential disputes, linking individual incidents, and conducting risk assessments.

Specific Responses to Retaliatory Violent Disputes

A wide range of interventions can be used to prevent retaliatory violence. These interventions work best when they are tailored to the unique circumstances of each particular dispute. Dispute interventions are of three basic types: investigative interventions, extended-enforcement interventions, and direct- prevention interventions. It is important to note that while all of the interventions suggested below have been used by police, not all of them have been proven to reduce retaliatory violence. Your selection of responses should be driven by the dispute circumstances and resources available to your department. Additionally, you should consult with your local legal counsel on the legal requirements of some responses.

Investigative Interventions

Investigative interventions prioritize criminal arrest as an objective. Custodial arrests can prevent subsequent violence by incapacitating dispute participants and deterring other dispute participants from engaging in subsequent retaliatory violence. Moreover, the filing of criminal charges can provide leverage that might be helpful with regard to other preventive measures.

1. Prioritizing investigation of incidents known to be related to an active, potentially violent dispute. This calls for deviating from conventional investigative priorities that are based primarily on the seriousness of the offense and solvability factors.

2. Referring high-priority investigations to special investigative units. Special investigative tactics such as electronic or plainclothes surveillance can be useful in developing evidence sufficient to arrest dispute participants for past violence or drug or vice crimes.58 These arrests can incapacitate dispute participants, lead to the development of new intelligence related to the dispute, and provide additional investigative leverage.

3. Debriefing dispute participants and knowledgeable others. This technique can develop new intelligence related to the dispute. A key element is securing the crime scene, particularly to ensure that all witnesses are interviewed about the potential for retaliatory violence.59

4. Monitoring jail conversations/telephone calls. This can lead to the development of new intelligence that aids in the investigation of dispute-related incidents and enhancement of dispute-prevention strategies. Disputants often share important details about causes of the dispute, the principal actors, locations where dispute-related violence occurred, and the types of weapons used.60

5. Monitoring dispute participants’ social media. Social media has become an important forum for tracking dispute-related activity.61 Disputants often will brag about the victimization of rivals and make threats of subsequent violence. In some cases, dispute participants have posted pictures of the weapons and vehicles used in dispute-related assaults. There are also instances when dispute participants arrange appointments to meet for the continuation of retaliatory violence.

6. Canvassing neighborhoods. Neighborhood canvasses can provide street intelligence on dispute characteristics relevant to the investigation and access to witnesses who, while reluctant to testify in court, can provide important street intelligence about disputes.

7. Referring retaliatory disputes to school resource officers (SRO) for additional information. SROs often know the history and social networks of school-aged disputants. This helps investigators understand dispute motives and identify others who may be able to provide information about the dispute. SROs are particularly helpful gathering intelligence on school-aged disputants who are affiliated with gangs or other problem groups.

8. Referring retaliatory disputes to mental health agencies. In cases where disputants have a documented mental illness, police may consult with mental health agencies to determine the best strategies to effectively reduce levels of violence. In some cases, a disputant’s underlying mental disorder may be contributing to the dispute and may be treatable.

Extended-Enforcement Interventions

Extended-enforcement interventions are those that address behavior and conditions outside the most recent dispute incidents.

9. Targeting enforcement on key individuals. Targeted enforcement of key individuals can interrupt dispute- related violence by incapacitating the most violent disputants.62 However, incapacitating key individuals may not end the dispute if known associates are willing and able to carry out further violence.

10. Saturating high-risk areas with patrol. This strategy can temporarily deter dispute participants from engaging in retaliatory violence. Saturation patrol can also increase opportunities to collect intelligence relevant to the investigation.

11. Searching homes for weapons and dispute intelligence. Often, at least some of the disputants are on either probation or parole. In cases where suspected disputants are on parole or probation, and probable cause is established, the property of probationers and parolees can be searched as a condition of their supervision.¶ These searches can sometimes generate important intelligence related to the dispute, including weapons. Furthermore, probation or parole violations that lead to incarceration can temporarily incapacitate probationers/parolees that are engaged in a dispute, thereby reducing the risk for retaliatory violence.

¶ As laws and policies governing police searches vary significantly across countries, states, and police agencies, you should consult your agency’s legal counsel for advice before adopting this strategy.

Parents, spouses, and roommates of disputants may wish to cooperate with law enforcement, particularly when they believe the continued dispute will result in their child, spouse, roommate, or themselves being harmed incarcerated. Consent searches can help find guns or other weapons and can provide useful intelligence for the investigation of dispute-related violence.63

12. Conducting warrant checks and checks of unresolved driving infractions and violations. Dispute participants sometimes have outstanding cases, active warrants, or license and moving violations. These can provide leverage for law enforcement and may even lead to the temporary incapacitation of dispute participants, thereby reducing the likelihood of subsequent retaliatory violence.

13. Tracking probationers and parolees via electronic monitoring. Electronic monitoring of probationers, parolees, or defendants on bail release can help authorities track high-risk actors who may be involved in retaliatory disputes. Access to GPS monitoring can help authorities determine if actors were in the vicinity of particular dispute incidents. This can help police determine if particular subjects should receive special attention or be ruled out as suspects in the investigation.

14. Conducting social service checks and enforcing related violations. Police can work with social service agencies to investigate services for disputants and their families to avoid violence.

15. Conducting knock-and-talk home visits. Police, perhaps accompanied by social-service providers or clergy can visit the homes of youth believed to be engaged in retaliatory violence.64 This can also yield new intelligence about the dispute.

16. Communicating directly with disputants. This could include a range of strategies from formal letters from police or prosecution officials to home visits in order to personally deliver messages dealing with dispute resolution strategies, services and, deterrence.†

† See Focused Deterrence of High-risk Individuals, Response Guide No. 13 for further information.

17. Executing emergency detentions of mentally ill, violent disputants. Some disputants may have mental health issues. Making a mental health detention can temporarily incapacitate dispute participants and may provide access to treatment which reduces the likelihood of further violence in the dispute.

Direct-Prevention Interventions

Direct-prevention interventions involve direct preventive action other than arrest.

18. Enforcing property and business codes. Property code enforcement reduces the likelihood that disputants congregate in or around problem areas. Vacant houses and commercial buildings can sometimes become magnets for dispute-related violence because the lack of social control in such settings can lead to the promotion of vice and violence.65 Cincinnati police were able to reduce violent crime significantly by improving control over networked places where violence—including retaliatory dispute violence—occurred or was staged.66

19. Referring disputants to street outreach workers. Police can refer disputes to street outreach workers when disputants are not amenable to police intervention. The street outreach workers can develop a plan to deter subsequent retaliatory violence.67

20. Referring disputants to local community, legal, or religious organizations that specialize in mediation or dispute resolution. Many cities have non-profit entities that offer free dispute-resolution services to reduce violence. Police can actively refer disputants to such services. These services can be used in isolation, or in combination with some other approach.

21. Engaging significant others in exercising informal social control. Significant others often cooperate with law enforcement and provide important intelligence on the dispute. Engaging significant others can help alert them concerning the serious nature dispute. This may lead them to engage their significant other in a manner that reduces the likelihood of subsequent retaliatory violence. Examples of significant others that can be engaged include romantic partners, family members, and friends.

22. Having police officers actively mediate disputes. Police can meet with dispute parties to discourage retaliation and mediate or negotiate settlements when serious crimes have not yet occurred. The police department could establish a cadre of trained negotiators.

23. Assisting disputants in relocating to avoid disputes. Disputants often wish to end the violence, but have no place of refuge that can shield them from potential retaliation. Providing relocation assistance can remove disputants from the theatre of operations and decrease the likelihood of subsequent retaliatory violence.‡

‡ For further information, see Problem-Specific Guide No. 42, Witness Intimidation.

24. Assisting disputants in negotiating or settling debts. A significant number of the disputes begin as a result of conflicts over money or property. Negotiating debt between disputants can help resolve the dispute and reduce the likelihood of subsequent retaliatory violence.

25. Linking disputants to social services. Provision of social services can help to divert dispute participants to a conventional lifestyle by (re)connecting them to prosocial others and institutions.§

§ See Focused Deterrence of High-risk Individuals, Response Guide No. 13 for further information.

26. Linking disputants to recreational activities. Recreation centers such as Boys and Girls Clubs can provide a safe space for children living in high-crime areas. Unfortunately, these centers can also sometimes serve as incubators of criminal activity. Police can work closely with administrators of such centers to ensure that dispute-related activity is not carried out on the premises of recreational centers. Recreation center staff may also possess important intelligence on dispute-related activity.

27. Conducting focused-deterrence call-ins and custom notifications with disputants. Focused-deterrence call- ins can be utilized to deter disputants and associates from engaging in subsequent retaliatory violence.§§ The extent to which call-ins can aid in reduction of retaliatory violence in your jurisdiction will be contingent upon your ability to implement an effective call-in program that can be incorporated within a broader strategy to reduce retaliatory violence. Custom notifications can be sent directly to disputants and the message can be tailored to particular individuals. This approach is particularly useful when there is not enough time to schedule a focused-deterrence call-in.

§§ See Focused Deterrence of High-risk Individuals, Response Guide No. 13 for further information.

How to Start a Retaliatory Violence Reduction Program

If your jurisdiction is interested in starting an initiative to reduce retaliatory violence, you should take the following major steps:

- Understand the nature of retaliatory violence in your community. To accomplish this task, it may be necessary to solicit support from a research partner. Collecting and analyzing local data can provide insight on the most appropriate ways to respond to the problem in your jurisdiction.

- Develop a clear set of protocols to determine when and how your department will respond to retaliatory disputes. This protocol should establish when risk assessment is warranted, a process for reviewing disputes, a process for responding to disputes, and a mechanism to track and monitor the strategies used and their effects.

- Implement a robust training regimen for officers, crime analysts, and law enforcement partners that will be working on this project. This training should provide clear guidelines on the roles and responsibilities of all actors, including: patrol officers, command staff, crime analysts, and other law enforcement personnel.

- Establish a mechanism to assess the implementation of the project and determine what is going well and changes that need to be made to fit the unique needs of your jurisdiction.