Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Tools Assessing Responses to Problem, 2nd Ed Page 1

Assessing Responses to Problems: Did It Work?

An Introduction for Police Problem-Solvers, 2nd Edition

Tool Guide No. 1 (2017)

by John E. Eck

Translations: Revisando las Respuestas a los Problemas, 2da Edición

Introduction

The purpose of assessing problem-solving efforts is to help police managers make better decisions. Assessments answer two specific questions: Did the problem decline? If so, did the planned response cause this decline? Answering the first question helps decision-makers determine whether a problem-solving effort can be ended, and whether resources can be redeployed to other problems. Answering the second helps decision-makers determine whether the response should be used again to address other, similar problems.

What This Guide is About

This guide is meant to help the reader design evaluations that can answer these two questions. It was written for police officials and others who are responsible for evaluating the effectiveness of responses to problems. It assumes that the reader has a basic understanding of problem-oriented policing and the problem-solving process, including the SARA (Scanning, Analysis, Response, and Assessment) process. It is designed to be useful to readers who have no experience with evaluation and no background in evaluation and research methods.

This guide also assumes that the reader has no outside assistance. Nevertheless, the reader should seek the advice and help of researchers with training and experience in evaluation, particularly if the problem being addressed is large and complex. An independent outside evaluator can be particularly useful if there is controversy over the usefulness of the response.

Throughout, this guide refers to the importance of distinguishing between these two questions:

- Has the problem declined following the response?

- Did the response cause the decline?

It is likely that answering the first question is more critical to you than answering the second.

This guide complements the guides in the Problem-Specific Guides and Response Guides series of the Problem-Oriented Guides for Police. Each problem-specific guide describes responses to a specific problem and suggests ways of measuring the problem. Each response guide describes how and whether that response works in addressing various problem types. Though this guide is designed to work with these problem-specific and response guides, readers should be able to apply the principles of evaluation in any problem-solving project.

Because this guide is an introduction to a complex subject, it omits much that would be found in an advanced text on evaluation.† Readers who wish to explore the topic of evaluation in greater detail should consult the list of recommended readings at the end of this guide.

† Specifically excluded from this discussion are mentions of measurement theory, significance testing, and statistical estimation. A monograph of this length cannot describe those issues in enough detail for them to be useful to the reader.

Related Guides in the Problem-Solving Tools Series

This guidebook complements others in the Problem-Solving Tools series. These guidebooks address various aspects of the four phases of problem solving.‡

‡ Some guidebooks address aspects of more than one phase of the problem-solving model.

Scanning phase:

- Identifying and Defining Policing Problems (Guide No. 13)

Analysis phase:

- Researching a Problem (Guide No. 2)

- Using Offender Interviews to Inform Police Problem Solving (Guide No. 3)

- Analyzing Repeat Victimization (Guide No. 4)

- Partnering with Businesses to Address Public Safety Problems (Guide No. 5)

- Understanding Risky Facilities (Guide No. 6)

- Using Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design in Problem Solving (Guide No. 8)

- Enhancing the Problem-Solving Capacity of Crime Analysis Units (Guide No. 9)

- Analyzing and Responding to Repeat Offending (Guide No. 11)

- Understanding Theft of ‘Hot Products’ (Guide No. 12)

Response Phase:

- Analyzing Repeat Victimization (Guide No. 4)

- Partnering with Businesses to Address Public Safety Problems (Guide No. 5)

- Understanding Risky Facilities (Guide No. 6)

- Implementing Responses to Problems (Guide No. 7)

- Using Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design in Problem Solving (Guide No. 8)

- Analyzing and Responding to Repeat Offending (Guide No. 11)

- Understanding Theft of ‘Hot Products’ (Guide No. 12)

Assessment Phase:

- Analyzing Repeat Victimization (Guide No. 4)

- Using Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design in Problem Solving (Guide No. 8)

- Analyzing Crime Displacement and Diffusion (Guide No. 10)

- Analyzing and Responding to Repeat Offending (Guide No. 11)/li>

- Understanding Theft of ‘Hot Products’ (Guide No. 12)

How Assessment Aids Police Decision Making

In any problem-solving effort, two key decisions must be made. First, did the problem decrease enough that the problem-solving effort can be scaled back and the police resources applied somewhere else? If the problem did not decrease substantially, the job is not over. In such a case, the most appropriate decision may be to re-analyze the problem and develop a new response. Further, future problem solvers should be alerted so that they can develop better responses to similar problems. If the problem has declined substantially, there may be limited need to continue the problem-solving effort beyond monitoring the problem and keeping track of any response maintenance that might be required. This first decision—deciding when the problem-solving effort is done—is this guide’s primary focus.

Second, if the problem did decline substantially, did the planned response cause the decline? If this decline is at least partially due to the response, it might be useful to apply a similar response to similar problems. If you cannot convincingly establish that the response caused the problem’s decline, reapplying the response to similar problems may not be useful. So, future decisions about whether to apply the response are driven in part by assessment information. In this regard, assessment is an essential part of police organizational learning. Without assessments, problem solvers may repeat their or others’ mistakes, or fail to benefit from their or other’ successes.

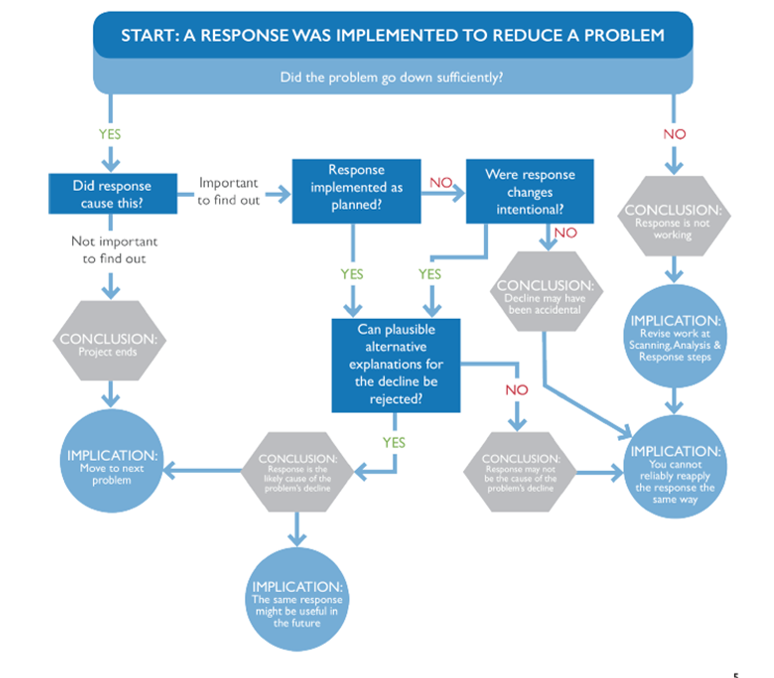

Figure 1: How Assessment Aids Police Decision-Making

The process begins with the implementation of some response intended to substantially reduce the problem. The meaning of “substantially” depends on the nature of the problem and the goals of the decision-makers. The first question is whether the problem declined substantially. If the answer is no, it is clear that the response is not working well enough. Assuming that sufficient time has elapsed that you are confident the response has had time to take effect, the implication is clear: you need to go back to earlier stages of the SARA process and make revisions. Further, you now have information indicating that this response should not be recommended in the future. Let’s assume that the problem has declined substantially. If you do not need to determine that the response was responsible for this decline, you can end the project and move on to the next problem. But if you take this course, you will not learn whether the response is a useful one to use in the future.

If it is important to find out whether the response caused the problem to decline, the next question is whether the response was implemented as planned. If it was not, and alterations to the response were unintentional, you do not know why the problem declined. Unintentional alterations include failure of a police unit to carry out its assigned role due to poor supervision, departures from the plan by partner agencies that are based on unforeseen circumstances (budget cuts, the appointment of a leader unsympathetic with the response, or administrative ineptitude). Success under these circumstances is welcome, but you cannot take credit for it, and you have insufficient grounds to recommend the response for similar problems.

If the response was implemented as planned, or the revisions to the response were deliberate, the next question is whether something outside of the response could have caused the problem’s decline. In principle, you can never be certain. In practice, this question comes down to, “Can I credibly reject all plausible specific alternative explanations for the problem’s decline?” If the answer is “no,” it is possible that something other than the response is responsible for the decline. So, you cannot definitively recommend the use of the response for future problems. Any such recommendation must be cautious. If the answer is “yes,” you have reasonably strong evidence that this response might work again.

Please note the qualifications in the language here. We can never be certain that a response will work the same way in the future. Instead, we can think of recommendations as being like bets: If I were to stake money on the outcome of my recommendation, am I more likely to win the bet or lose? Evidence helps you win more of these bets than you lose, but you will never win them all.

Coming to sensible conclusions requires a detailed understanding of three things: the nature of the problem; the manner by which the response is supposed to reduce the problem (see below); and the context within which the response has been implemented.1 For this reason, the evaluation process begins as soon as the problem is first identified during the scanning stage.

This guide discusses two simple designs: pre-post, and interrupted time series. The first is only useful in the first type of decision—whether to end a problem-solving effort. The time series design can aid in both types of decisions. Designs involving comparison (or “control”) groups are described in an appendix of this guide rather than in the main text. They can be difficult for a problem solver to implement successfully without receiving more advice than can be provided in this guide. Nevertheless, these designs can provide the information needed to help make the second type of decision—whether to use the response again in similar circumstances.

This guide is organized as follows.

- The body of the guide describes fundamental issues constructing simple but useful evaluations.

- The Recommended Readings list link this guide to more technical books on evaluation. Many of these clarify terminology.

- The appendices expand on material presented in the text and should be examined only after the text is read.

- Appendix A uses an extended example to show why evaluating responses over longer periods provides a better understanding of the effectiveness of the response.

- Appendix B describes five designs using data from a rigorous evaluation of a problem-solving project. (It includes three designs not discussed in the body of the guide: one you should never use, and two more-advanced designs.)

- Appendix C provides a checklist designed to walk a problem solver through the evaluation process, help select the most applicable design, and draw reasonable interpretations from evaluation results.

- Appendix D provides a summary of the strengths and weaknesses of the designs.

In summary, this guide explains in ordinary language those aspects of evaluation methods that are most important to police when addressing problems. In the next section, we will examine how evaluation fits within the SARA problem-solving process. We will then examine the two major types of evaluation—process and impact.