Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Patterns of Repeat Victimization

This guide begins by describing the concept of repeat victimization (RV) and its relationship to other patterns in public safety problems, such as hot spots and repeat offenders. The guide then describes sources of information, and ways to determine the amount and characteristics of repeat victimization in your jurisdiction. Finally the guide reviews responses to repeat victimization from evaluative research and police practice.

This guide is intended as a tool to help police identify and understand patterns of repeat victimization for a range of crime and disorder problems. The guide focuses on techniques for determining the amount of RV for specific public safety problems and how analysis of RV generally may be used to develop more effective responses. This publication is not a guide to specific problems, such as burglary, domestic violence, or vehicle theft. You are encouraged to refer to other guides for an in-depth understanding of these problems.

For decades, much effort by police and citizens has been invested in crime prevention—such as marking property, establishing a Neighborhood Watch, conducting crime prevention surveys, hardening targets, increasing lighting, and installing electronic security systems.

While numerous crime prevention efforts are effective, many are adopted by persons, households, and institutions least at risk of being victimized. Crime prevention strategies are most effective when directed at those most likely to be victimized.

Linking crime prevention strategies with likely victims is a challenge because of the difficulty in predicting the most likely victims of crime. Taking steps to prevent that offense from occurring would be easier, if only police knew…

- What stores will be robbed?

- Whose homes will be burglarized?

- Which college students will be sexually assaulted?

It is often painfully obvious that some individuals, households, or businesses are particularly vulnerable to crime. Such vulnerability may be related to factors such as abusing alcohol, failing to secure property, being physically isolated, engaging in risky behaviors, or being in close proximity to pools of likely offenders.

While most people and places do not get victimized by crime, those who are victimized consistently face the highest risk of being victimized again. Previous victimization is the single best predictor of victimization. It is a better predictor of future victimization than any other characteristic of crime.†

† Lynch, Berbaum, and Planty (1998) disagree. Using data from the NCVS, the authors found that housing location, age, and marital status of the head of household, size, and changes in household composition were stronger predictors of repeat victimization for burglary than initial victimization in the United States. In addition, the authors found that the best predictor of repeat victimization for assault was the reporting of an initial assault to the police.

Not only is repeat victimization predictable, the time period of likely revictimization can be calculated since subsequent offenses are consistently characterized by their rapidity. Much repeat victimization occurs within a week of an initial offense, and some repeat victimization even occurs within 24 hours. Across all crime types, the greatest risk of revictimization is immediately after the initial offense, and this period of heightened risk declines steadily in the following weeks and months.

The predictability of repeat victimization and the short time period of heightened risk after the first victimization provide a very specific opportunity for police to intervene quickly to prevent subsequent offenses. Strategies to reduce revictimization can substantially increase the effectiveness of police. Reducing repeat victimization can result in lower crime, improved efficiency of crime prevention resources, and the apprehension of offenders. It can also conserve both patrol and investigative resources.

Defining Repeat Victimization

In basic terms, repeat victimization is a type of crime pattern. There are several types of well-known crime patterns including hot spots, crime series, and repeat offenders. While repeat victimization is a distinct crime pattern, some offenses feature multiple crime patterns; these patterns are discussed later in this guide.

By most definitions, repeat victimization, or revictimization, occurs when the same type of crime incident is experienced by the same—or virtually the same—victim or target within a specific period of time such as a year. Repeat victimization refers to the total number of offenses experienced by a victim or target including the initial and subsequent offenses. A person's house may be burglarized twice in a year or 10 times, and both examples are considered repeats.

The amount of repeat victimization is usually reported as the percentage of victims (persons or addresses) who are victimized more than once during a time period for a specific crime type, such as burglary or robbery. Repeat victimization is also calculated as the proportion of offenses that are suffered by repeat victims; this figure is usually called repeat offenses. While both figures are important, they are not interchangeable and care should be taken in the reading of such numbers. In this guide, we report both proportions of repeat victims and repeat offenses when the data are available.

For example, the first row in Table 1 would be stated as:

- 46% of all sexual assaults were experienced by persons suffering two or more victimizations during the data period

Similarly, the second row in Table 2 would read:

- 11% of assault victims suffered 25% of all assaults over the 25-year period

And the first row in Table 3 would read:

- 40% of all burglaries were experienced by the 19% of victims who were victimized twice or more during the data period

The term "victimization" usually refers to people, such as a person who has been victimized by domestic violence. But repeat victimization can best be understood as repeat targets since a victim may be an individual, a dwelling unit, a business at a specific address, or even a business chain with multiple locations. Even motor vehicles may be repeat victims. Later in this guide, we discuss how to distinguish repeat victims in police data by address, victim's name, and other identifiers.

The Extent of Repeat Victimization

Repeat victimization is substantial and accounts for a large portion of all crime. While revictimization occurs for virtually all crime problems, the precise amount of crime associated with revictimization varies between crime problems, over time, and across places.† These variations reflect the local nature of crime and important differences in the type and amount of data used for computing repeat victimization. Three primary sources of information demonstrate that repeat victimization is prevalent across the world: surveys of victims, interviews with offenders, and crime reports. Although each of these sources has limitations, the prevalence of revictimization is consistent across these different sources.

† With the exception of Lynch, Berbaum, and Planty (1998), most estimates of repeat victimization are produced outside the United States and are drawn from the British Crime Survey, International Victims Survey, and other surveys. A few American studies in the early 1980s used the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) to examine repeat victimization but the NCVS is not designed to detect RV as it excludes crime "series," collects data only for incidents occurring in the preceding six months and uses a sample based on address that cannot control for people moving over time.

Table 1: Estimates of Repeat Victimization—International Victimization Survey1

Offenses | Repeat offenses |

|---|---|

| Sexual assault | 46% |

| Assault | 41% |

| Robbery | 27% |

| Vandalism to vehicle | 25% |

| Theft from vehicle | 21% |

| Vehicle theft | 20% |

| Burglary | 17% |

| Offense | Repeat Offenses | Repeat Victims | Data Source and Time Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assault | 25% | 11.4% | Emergency room reports, 25 years, Netherlands2 |

| Sexual assault | 85% | 67% | Victim surveys, adult experience, Los Angeles, California3 |

| Domestic violence | n/a | 44% | Victimization survey, one year, Great Britain4 |

| Assaults of youth | 90% | 59% | National Youth Survey, one year, United States5 |

| Offense | Repeat Offenses | Repeat Victims |

|---|---|---|

| Residential burglary6 | 40% | 19% |

| Vehicle crime (thefts of/from)7 | 46% | 24% |

| Vandalism8 | n/a | 30% |

| Offense | Repeat Offenses | Repeat Victims | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic violence | 62% | 28% | Merseyside, England9 |

| 42% | 31% | West Yorkshire, England10 | |

| Commercial robbery | 65% | 32% | Indianapolis, Indiana11 |

| Gas station robbery | 62% | 37% | Australia12 |

| Bank robbery | 58% | 36% | England13 |

| Residential burglary | 32% | 15% | Nottinghamshire, England14 |

| 13% | 7% | Merseyside, England15 | |

| 32% | 16% | Beenleigh, Australia16 | |

| 25% | 9% | Enschede, Netherlands17 | |

| Commercial burglary | 66% | 36% | Austin, Texas18 |

| 33% | 14% | Merseyside, England19 | |

| Residential and commercial burglary | 39% | 18% | Charlotte, North Carolina20 |

| Burglary | Vehicle Crime (Theft of/from) | Domestic Violence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| One offense | 81% | 76% | 56% |

| Two offenses | 13% | 17% | 21% |

| Three or more | 7% | 7% | 23% |

| Offense | Victims | Proportion of Offenses |

|---|---|---|

| One burglary | 81% | 60% |

| Two burglaries | 13% | 19% |

| Three or more burglaries | 7% | 21% |

| Offense | Proportion of Repeats by Time Period | Where/Study |

|---|---|---|

| Domestic violence | 15% within 24 hours 35% within five weeks | Merseyside, England25 |

| Bank robbery | 33% within three months | England26 |

| Residential burglary | 25% within a week 51% within a month | Tallahassee, Florida27 |

11% within one week 33% within one month | Merseyside, England28 | |

| Non-residential burglary | 17% within one week 43% within one month | Merseyside, England29 |

| Property crime at schools | 70% within a month | Merseyside, England30 |

Comparison data from international victimization surveys show that repeat victimization is more common for violent crime such as assaults and robbery than for property crime (see Table 1). Assault victims routinely feature a high rate of revictimization (see Table 2), and domestic violence is among the most predictable crimes for which a repeat will occur.

Repeat victimization is also common for property crime as evidenced in data from the British Crime Survey (see Table 3).

Although many studies of repeat victimization are based on surveys of victims, police records also show strong evidence of revictimization for problems ranging from bank robberies to domestic violence and burglaries (see Table 4). As with the victimization surveys, crime reports show the largest amount of repeat victimization for domestic violence.

While many repeat victims suffer two victimizations during a reporting period, some repeat offenses are associated with chronic victims who are victimized more often, experiencing three or more offenses during a period of time. The British Crime Survey reveals that 7 percent of burglary and vehicle crime victims are victimized three or more times during a year (see Table 5) while 23 percent of domestic violence victims suffer this concentration of repeat victimization.

The more numerous offenses reported by these chronic victims contribute disproportionately to overall victimization. For example, 7 percent of burglary victims comprise 21 percent of all burglaries (see Table 6).

Despite strong evidence of repeat victimization, virtually all estimates of repeat victimization are conservative because of data limitations. Victimization surveys show the most repeat victimization, because they capture offenses unreported to police. But longitudinal surveys lose respondents over time, as victims are likely to move, and panel surveys depend on a victim’s recall of multiple events. Interviews with offenders support repeat victimization but such studies have been limited and the veracity of offenders is questionable. Unreported crime reduces police estimates of repeat victimization and evidence even suggests that repeat victims are less likely to call the police again.[i] Police estimates of repeats may further exclude revictimization of the same individual at different locations, such as offenses reported from hospitals or at police stations while jurisdictional boundaries, recording practices for series offenses, the use of short-time periods such as a single year, and a small number of offenses may also mask repeats that can be identified by police.

When Repeat Victimization Occurs

A critical and consistent feature of repeat victimization is that repeat offenses occur quickly—many repeats occur within a week of the initial offense, and some even occur within 24 hours. An early study of RV showed the highest risk of a repeat burglary was during the first week after an initial burglary.[i]

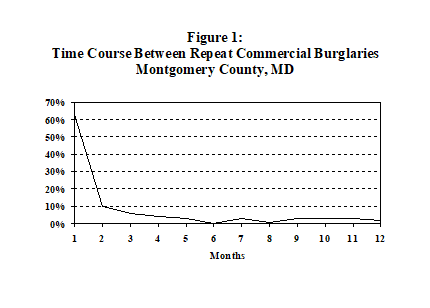

After the initial period of heightened risk, the risk of a repeat offense declines rapidly until the victim once again has about the same victimization risk as persons or properties that have never been victimized. This common pattern is displayed in Figure 1 and shows that 60 percent of repeat burglaries occurred within one month of the initial offense; about 10 percent occurred during the second month. After the second month, the likelihood of a repeat offense is quite low.

RV consistently demonstrates a predictable pattern known as time course: a relatively short high-risk period is followed by a rapid decline and then a leveling off of risk. The length of the time period of heightened victimization risk varies based on local crime problems. Determining the time period of heightened risk is critical because any preventive actions must be taken during the high risk period to prevent subsequent offenses. For offenses with a short high-risk time course, the preventive actions must be taken very quickly. The delay of two days or a week may miss the opportunity to prevent a repeat from occurring.

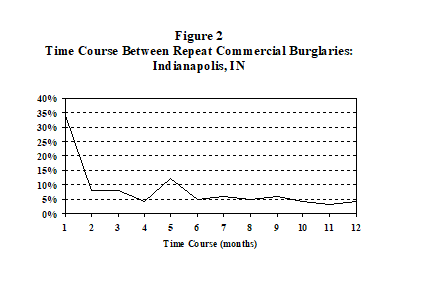

Some research suggests that the predictable time course of repeat victimization may be punctuated by a “bounce”—a slight resurgence in the proportion of revictimization occurring after the risk appears to be steadily declining (see Figure 2). The bounce in the time course may be associated with the replacement of property with insurance money. It seems likely that some repeat offenders may employ a “cool down” period, perceiving victims to be on high alert immediately after an offense but relaxing their vigilance within a few months.

Evidence suggests that the time period between an initial and subsequent offense varies by the type of crime. The time course of domestic violence appears short (see Table 7) with 15% of repeat offenses occurring within a day. The time course of RV may be calculated by hours, days, weeks or months, or even years between offenses, depending upon the temporal distribution of data.

In addition to variation by crime type, it is likely that the time course may also vary by the location of the study. For example, a study in Florida showed 25% of repeat burglaries took place within a week while a study in Merseyside showed 11% of repeats occurred during a similar time period.

Although the time period for reporting repeat victimization varies, the statement of such findings is straightforward. For example, the first row in Table 7 would be stated as:

Of repeat incidents of domestic violence, 15% occurred within 24 hours of the initial incident while 35% of repeat incidents occurred within five weeks.

Table 7:

Time Course of Repeat Victimization by Offense Type:

Crime Reports

Offense | Proportion of Repeats by Time Period | Where/Study |

Domestic violence | 15% within 24 hours 35% within five weeks | Merseyside, England[i] |

Bank robbery | 33% within three months | England[ii]

|

Residential burglary | 25% within a week 51% within a month | Tallahassee, Florida[iii] |

11% within one week 33% within one month | Merseyside, England[iv] | |

Non-residential burglary | 17% within one week 43% within one month | Merseyside, England[v]

|

Property crime at schools | 70% within a month | Merseyside, England[vi] |

Why Repeat Victimization Occurs

There are two primary reasons for repeat victimization: one, known as the “boost” explanation, relates to the role of repeat offenders; the other, known as the “flag” explanation, relates to the vulnerability or attractiveness of certain victims.

In the flag explanation, some targets are unusually attractive to criminals or particularly vulnerable to crime, and these characteristics tend to remain constant over time. In such cases, the victim is repeatedly victimized by different offenders.

- Some locations, such as corner properties, may have higher victimization because offenders can easily determine if no one is home. Similarly, apartments with sliding glass doors are particularly vulnerable to break-ins.

- Some businesses, such as convenience stores, are easily accessible and open long hours, which increases exposure to crime.

- Some jobs, such as taxi driving or delivering pizzas, routinely put employees at higher risk than do other jobs. People who routinely spend time in risky places, such as bars, are at greater risk of victimization.

- Hot products, such as vehicles desirable for joyriding, are at higher risk of being stolen.

In the boost explanation, repeat victimization reflects the successful outcome of an initial offense. Specific offenders gain important knowledge about a target from their experience and use this information to reoffend.

This knowledge may include easy access to a property, times during which a target is unguarded, or techniques for overcoming security. For example, offenders who steal particular makes of vehicles may have knowledge of ways to defeat their electronic security systems or locking mechanisms. Even fraudulent victimization shows this boost pattern, as insurance fraud may explain some cases of repeat victimization.

- During initial offenses, offenders may spot but be unable to carry away all the desirable property. These offenders may return for property left behind; or the offenders may tell others about the property, leading different offenders to revictimize the same property. Since many victims will eventually replace stolen property, such as electronics, original offenders may also return after a period of time to steal the replacement property—presumably brand new.[vii]

- Some victims may be unable to protect themselves from further victimization. An unrepaired window or door may increase vulnerability and make repeat victimization even easier than an initial offense. For example, once victimized, a domestic violence victim faces a high likelihood of revictimization if no protective measures are taken to prevent subsequent offenses.

- Interviews with offenders suggest that much repeat victimization may be related to boost explanations—experienced offenders can reliably calculate both the risks and rewards of offending. Half to two-thirds of offenders report burglarizing or robbing a specific property twice or more.[viii] Among domestic violence offenders, as many as two-thirds of incidents are committed by repeat offenders.[ix]

Boost and flag explanations may overlap and vary by offense type. For example, bank robberies are most likely to recur if an initial robbery yielded a large take; when monetary losses were small, banks were less likely to be robbed again.[x] Research on repeat victimization—for banks and other targets—suggests that most offenses are highly concentrated on a small number of victims while the majority of targets are never victimized at all.

How Repeat Victimization Relates to Other Crime Patterns

Research has revealed several types of repeat victimization:

- True repeat victims are the exact same targets that were initially victimized, such as the same house and the same occupants who were burglarized three times within a year.

- Near victims are victims or targets that are physically close to the original victim and may be similar in important ways. Apartments close to a burglarized unit will tend to contain similar goods, have similar physical vulnerabilities, and a common layout.

- Virtual repeats are repeat victims that are virtually identical to the original victim in important ways. A chain of convenience stores or fast food restaurants may have identical store layouts and management practices, such as having a single clerk on duty or informal cash handling procedures. The new occupants of a dwelling that had been previously burglarized are another type of virtual repeat.

- Chronic victims are repeat victims who suffer from different types of victimization over time—such as burglary, domestic violence, and robbery. This phenomenon is also known as multiple victimization.

For some crimes, repeat victimization is related to other common crime patterns:

- Hot spots are geographic areas in which crime is clustered. Hot spots may be hot because of the frequency of the same type of crime, such as burglaries, or hot spots may include different types of crimes. For many crimes, repeat victimization contributes to hot spots.

- Hot products are goods that are frequently stolen, and their desirability may underlie repeat victimization. Stores that sell CDs, beer, or gasoline may suffer repeat victimization. Some products, including vehicles, become hot products because of the product’s vulnerability—for example, vehicles with locks that are easy to defeat.

- Repeat offenders are individuals who commit multiple crimes. Some offenders specialize in a single crime type, while others commit complementary offenses—such as breaking into a house and stealing a vehicle to transport the goods, or stealing a license plate to be used in the commission of another crime, such as a commercial robbery.

- Crime series are offenses of one crime type that appear to be the work of the same offender. The offenses may be clustered in space or time, or reflect a distinctive modus operandi, such as a serial rapist who targets college students. Common series involve property crime at similar targets, such as robberies of convenience stores.

- Risky facilities are locations such as colleges or shopping areas that routinely attract or generate a disproportionate amount of crime. For example, lots where students routinely park may generate more larcenies from vehicles because the vehicles of students may routinely contain desirable electronic equipment.

These crime patterns are not mutually exclusive and may intersect or overlap; the detection of repeat victimization, however, routinely provides important clues about the reasons for recurrence and permits police to focus on avenues for prevention.

Where Repeat Victimization Occurs

For many crime problems, repeat victimization is most common in high crime areas.[1] Persons and places in high crime areas face a greater risk of initial victimization for many crimes, and they may lack the means to block a subsequent offense by improving security measures and doing so quickly.[xi]

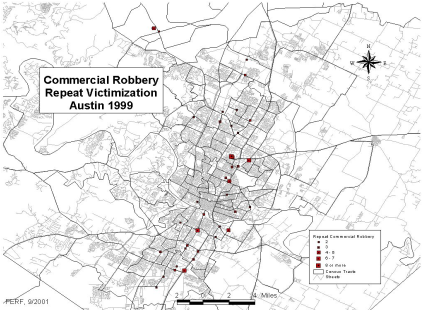

In high crime areas, crime is so concentrated among repeat victims that recurring offenses can create hot spots—relatively small geographic areas in which offenses are clustered. As a result, experts have coined the term “hot dots” because incident maps may be dominated by symbols scaled to represent the number of offenses at specific addresses.[xii] (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3

Repeat Commercial Robberies[i]

- [1] Offenses such as domestic violence and sexual assault do not usually exhibit spatial concentrations, while other targets of repeat victimization, such as convenience stores, budget motels, and banks, may be geographically dispersed.

Incident maps are often used to identify hot spots and can be used to detect repeat victimization. Icons or symbols should be used on maps that are scaled in size to reflect the number of incidents, otherwise points that overlap may not be visible, masking RV. Data decisions can also distort the amount of repeat victimization that can be detected on maps. Short time periods, such as a week or month or even a quarter—may mask repeat victimization; imprecise address information, such as a single address for incidents occurring at a large apartment complex, also mask specific locations of RV.

Incident maps may mask RV in densely populated areas because most maps demonstrate the incidence and spatial distribution of offenses, and do not account for the concentration of crimes. In densely populated areas such as those with multi-family dwellings, most maps will not differentiate between apartment units and apartment buildings that may comprise large apartment complexes.

Crime is not always geographically patterned, and this is also true for repeat victimization. For example, victims of domestic violence are unlikely to be geographically concentrated. Even repeat incidents of domestic violence may not occur at a single address; one offense may take place at a residence while the repeat offense may occur at a victim’s workplace.

Some crimes, such as burglary, are clustered geographically; repeat burglaries are even more predictably clustered.[i] Thus, citywide data on burglaries may mask the proportion of repeat burglaries occurring in smaller geographic areas. This suggests the need to use different geographic levels of analysis to examine RV. In contrast to burglary, offenses such as bank robberies and domestic violence may necessitate the use of data from the entire jurisdiction.

Overlooking Repeat Victimization

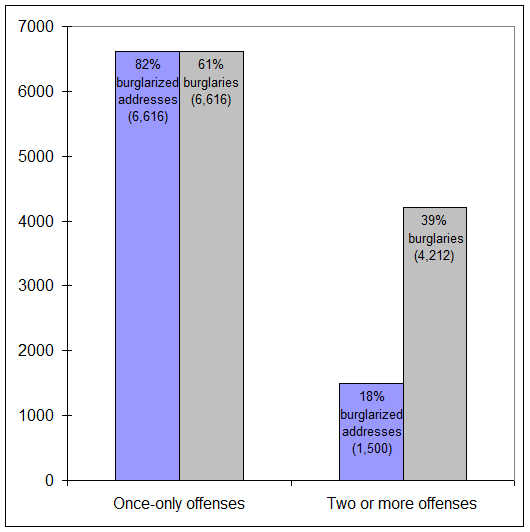

Consider a study in which 10,828 burglaries were reported to police in 1990:[ii]

- 97 percent of the city’s estimated 300,000 addresses were not burglarized

- 3 percent of the jurisdiction’s addresses (8,116) were burglarized

At first, repeat victimization appears minimal:

- 82 percent of the victims (6,616 addresses) suffered only one burglary during the year

- 18 percent of victims (1,500 addresses) suffered two or more burglaries

Analysis sheds further light on revictimization:

- 61 percent of all burglaries (6,616) occurred at addresses with only one offense

- 39 percent of all burglaries (4,212) occurred at addresses with two or more offenses

While repeat victimization may still appear minimal, Figure 4 demonstrates graphically that revictimization accounts for a disproportionately large share of all burglaries: 18 percent of victims accounted for 39 percent of burglaries. If offenses after the initial offense had been prevented, the jurisdiction would have experienced 2,712 fewer burglaries—a 25 percent reduction in burglaries.

Figure 4:

Distribution of Burglaries by Address and Frequency

In addition to its potential for crime reduction, analysis of repeat victimization provides an important analytic and management tool for police organizations by serving the following purposes:

- Provide a reliable performance measure for evaluating organizational effectiveness (as used by police forces in Great Britain).

- Serve as a catalyst for developing more effective responses for problems that generate much of the workload for police.

- Reveal limitations of existing data and police practices, and advance improvements in data quality and victim services. (See Appendix A for ways to easily improve data quality.)

- Provide insight into patterns underlying recurring crime problems.

- Prioritize the development and delivery of crime prevention and victim services.

Although recognizing repeat victimization is an important step, working out precisely what to do about revictimization will require additional effort on the part of police.

Special Concerns About Repeat Victimization

- Blaming the victim. Victims may be vulnerable because they are unable, or have failed to secure their property, or have placed themselves in high-risk settings. The behaviors of individuals—such as using poor judgment while under the influence of drugs or alcohol—may contribute to victimization. In most cases, police should provide information to the victim about the increased risk of victimization but must be careful about implying blame.

- Increasing fearfulness. For offenses such as burglary that are unlikely to be solved, the primary role of police is often to comfort victims. Warning victims about the likelihood of being revictimized may make victims more fearful.

- Violating privacy of victims. Although victimization increases the risk of revictimization to the original victim, it also increases the risks to persons and properties that are either nearby or virtually identical to the initial victim. While police may be concerned about violating the privacy of an initial victim by warning others, this information may prevent other vulnerable persons or places from being victimized.

- Displacing crime. It is often believed that thwarting one offense will result in a motivated offender simply picking another target. Unless there are virtual victims, the likelihood of displacement is low.[i] For example, preventing repeat domestic violence is unlikely to result in the displacement of violence to another victim. If there are virtual victims available—such as similar nearby houses to be burglarized or similar unsecured parking lots for vehicle theft—police should consider these as candidates for similar crime prevention strategies. Rather than causing displacement, crime prevention efforts focused on victims are just as likely to produce bonus effects. For example, reducing opportunities for vehicle theft may also reduce theft from vehicles.

- Unintended consequences. Focusing on repeat victimization to reduce offending may have unintended consequences. In a study in New York City, researchers found that follow-up visits and educational services to victims of domestic violence resulted in increased calls for police service,[ii] and mandatory arrest for some domestic violence offenders increases revictimization.