Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

The Problem of Chronic Public Inebriation

This guide begins by describing the problem of chronic public inebriation and reviewing factors that increase its risks. It then identifies a series of questions to help you analyze your local chronic public inebriation problem. Finally, it reviews responses to the problem and what is known about these from evaluative research and police practice.

What This Guide Does and Does Not Cover

The problem of chronic public inebriation takes many forms and has numerous negative social consequences.† While chronic inebriation occurs in many different settings, such as the home, workplace, and bars, this guide focuses on chronic inebriation in outdoor public spaces, with a particular emphasis on chronic inebriation among those who spend a good portion of their daily lives on the street.

As used in this guide, "chronic inebriation," "chronic inebriate," or "alcoholic" refer to individuals whose lives are dominated by the use or abuse of alcoholic beverages such that they have substantially withdrawn from conventional society.1, ‡

Chronic public inebriation is but one aspect of the larger set of problems related to alcohol abuse and street disorder. This guide is limited to addressing the particular harms created by chronic public inebriation. Related problems not directly addressed in this guide, each of which requires separate analysis, include:

† Multiple sources confirm the frequently conjoined issues of mental illness, homelessness, alcoholism and other substance abuse. See Bahr (1973), Finn (1985), Finn and Sullivan (1987), Snow and Anderson (1993), and Wiseman (1979).

‡ According to the World Health Organization, a person is alcohol dependent if he or she has three or more of the following six manifestations, occurring together for at least one month or repeatedly within one year: compulsion to drink, lack of control, withdrawal state, tolerance, salience, and persistent use (WHO 1992). The city of San Diego, California, employs a simple measure to classify an individual as a "chronic inebriate." Their criterion is whether the individual in question has been admitted five or more times to the city's sobering center within a 30-day period.

Problems Associated with Street Disorder

- Panhandling

- Disorderly behavior by mentally ill persons

- Homeless encampments

- Day laborer sites

- Student party riots

- Disorder in entertainment districts

- Disorderly youth in public places

- Indecent exposure

- Open intoxicants in public

Problems Associated With Chronic Inebriation in Private Places

- Domestic violence

- Child abuse and neglect

- Suicide

- Accidental death and injury

- Accidental fires

- Underage drinking

Other Problems Associated with Chronic Inebriation in Public Places

- Drunken driving

- Pedestrian injuries and fatalities

- Disorder in public libraries

- Disorder in public transportation systems

- Assaults in and around bars

Some of these related problems are covered in other guides in this series, all of which are listed at the end of this guide. For the most up-to-date listing of current and future guides, see www.popcenter.org.

General Description of the Problem

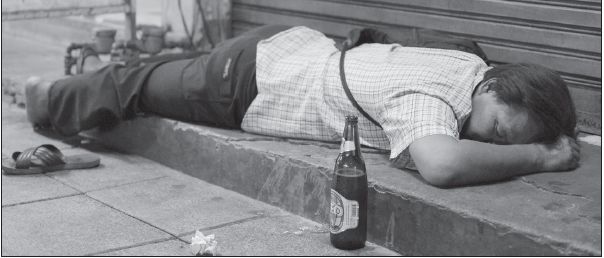

When chronically inebriated individuals disruptively or persistently violate community standards by being intoxicated, panhandling, acting aggressively, or passing out in places not "approved" for such behaviors, the police may be called to intervene. As is also the case in dealing with mentally ill and homeless populations, it is important to recognize that chronic public inebriation is not, in and of itself, solely a police problem. It is also a medical and social services problem. That said, a number of the problems caused by, associated with, or resulting from chronically inebriated individuals often manifest themselves as police problems, such as disorderly conduct, threats, public urination and defecation, passing out in public, thefts, and assaults.

Chronic public inebriates are nearly as likely to be victims of crime and other hazards as they are to be offenders, and some of that victimization will not be reported to police. Their inebriation leaves them less capable of defending and caring for themselves and their property. From a moral, legal, and professional standpoint, it is important to acknowledge that chronic inebriates do not forfeit the rights and expectations afforded all other members of the community just because they are caught up in a harmful or negative dynamic.

Photo Credit: © 1000 Words/Shutterstock No.81784615

Evolution of Chronic Inebriation Law and Policy

As far back as ancient Egypt, public policymakers battled problems associated with chronic public inebriation.2 Public intoxication was first criminalized by the English in 1606.3 By 1619, criminalization of public drunkenness reached the American colonies, but it took until 1810 before treatment of public inebriates began with Benjamin Rush's "sober houses."4

In the United States, beginning in the mid-1960s, law and public policy began shifting away from criminalizing public inebriation to treating it as a medical and public health problem,5, † a shift that helped foster the idea that effective responses to chronic public inebriation would not be solely a police responsibility but would require broader community action. In 1970, the Comprehensive Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Prevention, Treatment and Rehabilitation Act went into effect. This act provided state and local governments with financial resources to support alcohol-abuse reduction programs. It also created the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. By 1973, states were being pressed to decriminalize public drunkenness in favor of a social model based in treatment.6 In 1987, the federal government began funding alcohol-dependency treatment programs for homeless people.7

† U.S. courts have considered whether a homeless person might successfully invoke constitutional protections, such as the Eighth Amendment's prohibition against "cruel and unusual punishment," because they lacked a private place to drink. See, for example, Robinson v. California, 370 US 660 (1962) and Powell v. Texas, 392 US 514 (1968) for leading cases on this issue. See also McMorris (2006).

Harms Caused by Chronic Public Inebriation

Chronic public inebriation is commonly entwined with a number of specific behavioral problems and conditions, including the following:

- Sleeping in public‡

- Undiagnosed, untreated, or inconsistently treated mental illness8

- Disorderly conduct (noise, fighting, obstreperous behavior, etc.)

- Inappropriate use of public places (e.g., public libraries, sidewalks, benches, parks)

- Other substance abuse (e.g., use of or addiction to drugs)

- Public urination and defecation

- Panhandling, harassment, or intimidation of others

- Illegal lodging (e.g., sleeping or passing out in public places, or homeless encampments)

- Thefts and robbery (e.g., pickpocketing, robbery at ATMs, thefts from vehicles)

- Trash picking (for food or to salvage cans and bottles)

- Litter and increased public sanitation burdens

- Blocking pedestrian traffic (which can disrupt business and access to public transportation systems)

- Drug dealing

- Intimidation of other citizens (which can cause some to avoid or retreat from parks and other places where chronic inebriates gather)

‡ The likelihood of rehabilitation among individuals who are both alcoholics and homeless is exceedingly low (Argeriou and McCarty 1993; Podymow et al. 2006; Castaneda et al. 1992; Richman and Smart 1981; Richman and Neuman 1984; Cox et al. 1998). Another body of research, however, observes success among strategies predicated on stabilizing residency as an element of substance abuse counseling (Larimer et al. 2009; Grella 1993; Coffler and Hadley 1973).

Beyond street-level consequences, chronic inebriates pose a significant and disproportionate drain on public resources. In Anchorage, Alaska, almost 2,000 chronic inebriates accounted for approximately 19,000 visits to that city's sobering center in a single year.† Moreover, a mere 200 individuals accounted for 56 percent of all visits to the center during 2007.9 A study in San Diego, California, reached similar conclusions,‡ noting that the episodic emergency care demands created by chronic inebriates have a significant cumulative impact on the community's safety-response system through emergency room overcrowding, ambulance diversion, and a shortage of available bed space.10, § Roanoke, Virginia, provides a similar example: an analysis of that city's drunk-in-public arrests revealed that 2,642 different individuals were responsible for 4,099 incidents during 1997. Within this group, 45 individuals (1.7 percent) were responsible for 919 incidents (22.4 percent).11, ¶

† Throughout this document, the terms "sobering center" and "detoxification center" are used interchangeably to indicate a short-term facility where inebriated individuals can sober up in a protected environment.

‡ The City of San Diego studied the impact of 529 homeless alcoholics, many of whom also had other medical or mental illness issues, on public resources. From 2003 to 2005, 308 individuals (58 percent) were transported by emergency medical personnel 2,335 times, 409 individuals (77 percent) accounted for 3,318 emergency-room visits, and 217 individuals (41 percent) required 652 hospital admissions, resulting in 3,361 inpatient days. Health care charges totaled $17.7 million. Payment for only 18 percent of charges was received.

§ A study in the United Kingdom found that an alcoholic patient's use of health care services before getting treatment for alcohol abuse is up to 15 times greater than that of the general population, but after alcohol treatment these costs decline significantly (Malone and Friedman 2005).

¶ While a dated statistic, Bahr (1973:228) recounts that just six "alcoholic" individuals in the mid-1960s had been arrested in Washington, D.C., 1,409 times and had been incarcerated a combined total of 125 years. Figures like this are common even today.

The traditional police approach to the management of chronic inebriates has been characterized as "a rare mixture of almost paternal indulgence, strictness and an ad hoc decision-making not found elsewhere."12 Dealing with chronically inebriated individuals also exacts an emotional toll on police officers.13 It can lead, for example, to the following:

- Increased frustration stemming from officers' inability to render meaningful help, while at the same time knowing that the public demands they "do something."14

- Increased stress as a result of being thrust into situations for which they have little or no specialized training (e.g., resolving situations where a person is behaving irrationally or is mentally ill or under the influence of alcohol or other drugs).15

- Increased stress because they feel they are being asked to handle situations that aren't really "police problems."16

- Feeling overburdened at having to locate appropriate resources for or facilities willing to accept individuals in need of specialized accommodations or treatment.17

Taken together, chronic inebriates create a demand for service widely disproportionate to their numbers. Moreover, chronic inebriation (and its companion offenses) is often processed rapidly through criminal courts. Because individuals charged under public drunkenness statutes typically spend little time in custody, this creates a "revolving door" system in which all stakeholders suffer and service demands stay high.Beyond this, the prospect of reintegration into mainstream society is a daunting proposition for many chronic inebriates. Those individuals, who have spent so much of their lives on the streets, must relearn the basics of normal daily living. Many chronic inebriates have long-term cognitive damage from their rough lifestyles as well as underlying mental illnesses.18, †

† Deni McLagan with Mental Health Systems in San Diego talks about the difficulties of changing decades of dysfunctional behavior among long-time chronic inebriates: "The first 30 days we're modeling social behaviors with them, such as hygiene, riding the bus, feeding themselves, taking medications. We're just trying to get the guy to shave and bathe in the first month. In the second or third, we'll get them employment."

Factors Contributing to Chronic Public Inebriation

The level and degree of harm caused by chronic public inebriation is affected by a number of contributing factors, which may include the following:

Lack of adequate alcohol treatment, rehabilitation, and counseling services

This can compel police to deal with the problem solely as a criminal issue, with less than optimal results.

High concentrations of businesses that sell inexpensive alcohol

An area with many retailers of alcoholic beverages may attract chronic inebriates to the area and facilitate their problem behavior. However, hot spots—places where inebriates tend to concentrate and cause problems (e.g., parks, transit stations, the periphery of shelters, near liquor stores)—near businesses that sell alcohol do not necessarily coincide with dense clusters of the establishments themselves, nor do they coincide with areas in which general crime levels are high or with areas with a high level of lethal violence related to alcohol use.19

Densely populated areas

These areas are more likely to attract chronic inebriates, because they often are accompanied by better opportunities for procuring alcohol and the money needed to purchase it, as well as providing some measure of anonymity for inebriates.

Public transit stations, trains, and buses

Public areas tend to often serve as points of congregation for chronic inebriates, and poorly designed and managed ones facilitate problem behavior.

Laws and regulations

While normally designed to eliminate problems, sometimes laws and regulations that facilitate the sale of single-serving containers, fortified wines, malt liquor, and other low cost/higher alcohol-content beverages are likely to increase chronic inebriates' consumption and intoxication levels, and, thereby, their problem behavior.

Laws and public drunkenness

The existence of laws that criminalize—and the absence of laws that decriminalize—public inebriation provide resources for a medical-treatment response will shape how police and others are able to address the problem.

A high rate of homelessness

Whatever its cause, homelessness is likely to coincide with a high level of chronic public inebriation, because residential stability is an important predicate for effective substance abuse treatment.20

Predominant local standards for and sensibilities about public order

Each community usually has its local standards and sensibilities about public order. Some communities are considerably more tolerant than others of deviant or disorderly behavior in public. General community attitudes are usually then reflected in elected officials' attitudes towards the problem.

Police department operational priorities

Like individual communities, police departments also vary. Some police agencies can afford to devote personnel to the careful management of chronic public inebriation; others cannot.

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Chronic Public Inebriation

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.