Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Bullying in Schools

Guide No.12 (2002)

by Rana Sampson

Translation(s): O Bullying nas Escolas (Portuguese)

Hostigamientos en las escuelas (Español)

The Problem of Bullying in Schools

There is new concern about school violence, and police have assumed greater responsibility for helping school officials ensure students' safety. As pressure increases to place officers in schools, police agencies must decide how best to contribute to student safety. Will police presence on campuses most enhance safety? If police cannot or should not be on every campus, can they make other contributions to student safety? What are good approaches and practices?

Perhaps more than any other school safety problem, bullying affects students' sense of security. The most effective ways to prevent or lessen bullying require school administrators' commitment and intensive effort; police interested in increasing school safety can use their influence to encourage schools to address the problem. This guide provides police with information about bullying in schools, its extent and its causes, and enables police to steer schools away from common remedies that have proved ineffective elsewhere, and to develop ones that will work.†

† Why should police care about a safety problem when others, such as school administrators, are better equipped to address it? One can find numerous examples of safety problems regarding which the most promising part of the police role is to raise awareness and engage others to effectively manage the problems. For example, in the case of drug dealing in privately owned apartment complexes, the most effective police strategy is to educate property owners and managers in effective strategies so they can reduce their property's vulnerability to drug markets.

Bullying is widespread and perhaps the most underreported safety problem on American school campuses.1 Contrary to popular belief, bullying occurs more often at school than on the way to and from there. Once thought of as simply a rite of passage or relatively harmless behavior that helps build young people's character, bullying is now known to have long-lasting harmful effects, for both the victim and the bully. Bullying is often mistakenly viewed as a narrow range of antisocial behavior confined to elementary school recess yards. In the United States, awareness of the problem is growing, especially with reports that in two-thirds of the recent school shootings (for which the shooter was still alive to report), the attackers had previously been bullied. "In those cases, the experience of bullying appeared to play a major role in motivating the attacker."2, ‡

‡ It is important to note that while bullying may be a contributing factor in many school shootings, it is not the cause of the school shootings.

International research suggests that bullying is common at schools and occurs beyond elementary school; bullying occurs at all grade levels, although most frequently during elementary school. It occurs slightly less often in middle schools, and less so, but still frequently, in high schools.§ High school freshmen are particularly vulnerable.

§ For an excellent review of bullying research up through 1992, see Farrington (1993).

Dan Olweus, a researcher in Norway, conducted groundbreaking research in the 1970s exposing the widespread nature and harm of school bullying.3 Bullying is well documented in Europe, Canada, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand, providing an extensive body of information on the problem. Research from some countries has shown that, without intervention, bullies are much more likely to develop a criminal record than their peers,† and bullying victims suffer psychological harm long after the bullying stops.

† As young adults, former school bullies in Norway had a fourfold increase in the level of relatively serious, recidivist criminality (Olweus 1992). Dutch and Australian studies also found increased levels of criminal behavior by adults who had been bullies (Farrington 1993; Rigby and Slee 1999).

Definition of Bullying

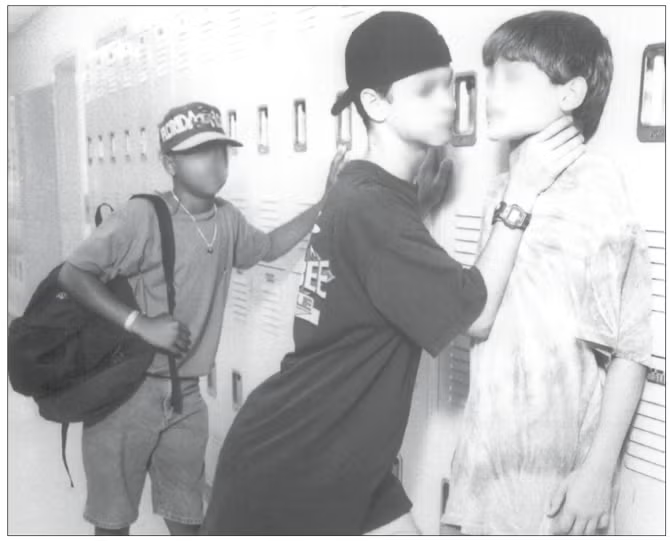

Bullying has two key components: repeated harmful acts and an imbalance of power. It involves repeated physical, verbal or psychological attacks or intimidation directed against a victim who cannot properly defend him- or herself because of size or strength, or because the victim is outnumbered or less psychologically resilient.4

Bullying includes assault, tripping, intimidation, rumor-spreading and isolation, demands for money, destruction of property, theft of valued possessions, destruction of another's work, and name-calling. In the United States, several other school behaviors (some of which are illegal) are recognized as forms of bullying, such as:

- Sexual harassment (e.g., repeated exhibitionism, voyeurism, sexual propositioning, and sexual abuse involving unwanted physical contact)

- Ostracism based on perceived sexual orientation

- Hazing (e.g., upper-level high school athletes' imposing painfully embarrassing initiation rituals on their new freshmen teammates)5

Not all taunting, teasing and fighting among schoolchildren constitutes bullying.6 "Two persons of approximately the same strength (physical or psychological)…fighting or quarreling" is not bullying. Rather, bullying entails repeated acts by someone perceived as physically or psychologically more powerful.

Related Problems

Bullying in schools shares some similarities to the related problems listed below, each of which requires its own analysis and response. This guide does not directly address these problems:

- Bullying of teachers by students

- Bullying among inmates in juvenile detention facilities

- Bullying as a means of gaining and retaining youth gang members and compelling them to commit crimes.

Extent of the Bullying Problem

Extensive studies in other countries during the 1980s and 1990s generally found that between 8 and 38 percent of students are bullied with some regularity,† and that between five and nine percent of students bully others with some regularity. Chronic victims of bullying, bullied once a week or more, generally constitute between 8 and 20 percent of the student population.7

† A South Carolina study found that 20 percent of students bully others with some regularity (Limber et al. 1998). In an English study involving 25 schools and nearly 3,500 students, 9 percent of the students admitted to having bullied others by sexual touching [Glover and Cartwright, with Gleeson (1998)].

In the United States, fewer studies have been done. A recent study of a nationally representative sample of students found higher levels of bullying in America than in some other countries. Thirteen percent of sixth- through tenth-grade students bully, 10 percent reported being victims, and an additional six percent are victim-bullies.8 This study excluded elementary-age students (who often experience high levels of bullying) and did not limit bullying to school grounds. Several smaller studies from different parts of the country confirm high levels of bullying behaviors, with 10 to 29 percent of students reported to be either bullies or victims.9, ‡

‡ In some of the studies, lack of a common definition of bullying potentially distorts the estimates of the problem (Harachi, Catalano and Hawkins 1999). In addition, in the United States, the lack of a galvanized focus on bullying has resulted in a lack of large-scale school research efforts (such as those in Scandinavia, England, Japan, and Australia). Thus we have only limited insights into the problem of bullying here.

Clearly, the percentage of students who are bullies and victims varies by research study, often depending on the definition used, the time frame examined (e.g., ever, frequently, once a week)† and other factors.‡ Despite these differences, bullying appears to be widespread in schools in every country studying the problem.§

† For the first time, during the 1997-98 school year, the United States participated in an international study of young people's health, behavior and lifestyles, which included conducting surveys on school bullying. (European countries have participated in the study since 1982.) Researchers gathered data on 120,000 students from 28 countries. Upwards of 20 percent of 15-year-old U.S. students reported they had been bullied at school during the current term (see "Annual Report on School Safety." However, a 2000 U.S. Department of Education report on school crime (based on 1999 data), using a very narrow—and perhaps too limited—definition of bullying than the earlier report, showed that 5 percent of students ages 12 through 18 had reported being bullied at school in the last six months (Kaufman et al. 2000).[Full text ] [Full text ]

‡ The "Annual Report on School Safety," developed in response to a 1997 school shooting in West Paducah, Kentucky, did not until 1999 contain any data on school bullying. The 1999 school bullying data are aggregate, useful only in international comparisons, since specific types of bullying are not categorized. The report tracks thefts, weapons, injuries, threats, and physical fights, and some measures of harassment and hate crimes. However, the proportion of incidents that have their roots in bullying is not specified.

§ The words "bully" and "bullying" are used in this guide as shorthand to include all of the different forms of bullying behavior.

A Threshold Problem: The Reluctance to Report

Most students do not report bullying to adults. Surveys from a variety of countries confirm that many victims and witnesses fail to tell teachers or even parents.10 As a result, teachers may underestimate the extent of bullying in their school and may be able to identify only a portion of the actual bullies. Studies also suggest that children do not believe that most teachers intervene when told about bullying.11

"If the victims are as miserable as the research suggests, why don't they appeal for help? One reason may be that, historically, adults' responses have been so disappointing."12 In a survey of American middle and high school students, "66 percent of victims of bullying believed school professionals responded poorly to the bullying problems that they observed."13 Some of the reasons victims gave for not telling include:

- Fearing retaliation

- Feeling shame at not being able to stand up for themselves

- Fearing they would not be believed

- Not wanting to worry their parents

- Having no confidence that anything would change as a result

- Thinking their parents' or teacher's advice would make the problem worse

- Fearing their teacher would tell the bully who told on him or her

- Thinking it was worse to be thought of as a snitch.†

† Similarly, many sexual assault and domestic violence victims keep their abuse a secret from the police. Police in many jurisdictions see increased reporting of these crimes as an important first step to reducing the potential for future violence, while victims often see it as jeopardizing their safety. Some of the same interests and concerns are found in the area of school bullying.

The same is true of student-witnesses. Although most students agree that bullying is wrong, witnesses rarely tell teachers and only infrequently intervene on behalf of the victim. Some students worry that intervening will raise a bully's wrath and make him or her the next target. Also, there may be "diffusion of responsibility"; in other words, students may falsely believe that no one person has responsibility to stop the bullying, absent a teacher or a parent.

Student-witnesses appear to have a central role in creating opportunities for bullying. In a study of bullying in junior and senior high schools in small Midwestern towns, 88 percent of students reported having observed bullying.14 While some researchers refer to witnesses as "bystanders," others use a more refined description of the witness role. In each bullying act, there is a victim, the ringleader bully, assistant bullies (they join in), reinforcers (they provide an audience or laugh with or encourage the bully), outsiders (they stay away or take no sides), and defenders (they step in, stick up for or comfort the victim).15 Studies suggest only between 10 and 20 percent of noninvolved students provide any real help when another student is victimized.16

Bullying Behavior

Despite country and cultural differences, certain similarities by gender, age, location, and type of victimization appear in bullying in the U.S. and elsewhere.

- Bullying more often takes place at school than on the way to and from school.17

- Boy bullies tend to rely on physical aggression more than girl bullies, who often use teasing, rumor-spreading, exclusion, and social isolation. These latter forms of bullying are referred to as "indirect bullying." Physical bullying (a form of "direct bullying") is the least common form of bullying, and verbal bullying (which may be "direct" or "indirect") the most common.18 Some researchers speculate that girls value social relationships more than boys do, so girl bullies set out to disrupt social relationships with gossip, isolation, silent treatment, and exclusion. Girls tend to bully girls, while boys bully both boys and girls.

- Consistently, studies indicate that boys are more likely to bully than girls.

- Some studies show that boys are more often victimized, at least during elementary school years; others show that bullies victimize girls and boys in near equal proportions.19

- Bullies often do not operate alone. In the United Kingdom, two different studies found that almost half the incidents of bullying are one-on-one, while the other half involves additional youngsters.20

- Bullying does not end in elementary school. Middle school seems to provide ample opportunities for bullying, although at lesser rates. The same is true of the beginning years of high school.

Bullying by boys declines substantially after age 15. Bullying by girls begins declining significantly at age 14. 21, † So interventions in middle and early high school years are also important.

† Results from several countries, including Australia and England, indicate that as students progress through the middle to upper grades in school, they become more desensitized to bullying. High school seniors are the exception: they show greater alarm about the problem, just at the point when they will be leaving the environment (O'Moore 1999).

- Studies in Europe and Scandinavia show that some schools seem to have higher bullying rates than others. Researchers generally believe that bullying rates are unrelated to school or class size, or to whether a school is in a city or suburb (although one study found that reporting was higher in inner-city schools). Schools in socially disadvantaged areas seem to have higher bullying rates,22 and classes with students with behavioral, emotional or learning problems have more bullies and victims than classes without such students.23

- There is a strong belief that the degree of the school principal's involvement (discussed later in this guide) helps determine the level of bullying.

- There is some evidence that racial bullying occurs in the United States. In a nationally representative study combining data about bullying at and outside of school, 25 percent of students victimized by bullying reported they were belittled about their race or religion (eight percent of those victims were bullied frequently about it).24 The study also found that black youth reported being bullied less than their Hispanic and white peers. Racial bullying is also a problem in Canada and England. "In Toronto, one in eight children overall, and one in three of those in inner-city schools, said that racial bullying often occurred in their schools."25 In four schools—two primary, two secondary—in Liverpool and London, researchers found that Bengali and black students were disproportionately victimized.26

One of the things we do not yet know about bullying is whether certain types of bullying, for instance racial bullying or rumor spreading, are more harmful than other types. Clearly, much depends on the victim's vulnerability, yet certain types of bullying may have longer-term impact on the victim. It is also unclear what happens when a bully stops bullying. Does another student take that bully's place? Must the victim also change his or her behavior to prevent another student from stepping in? While specific studies on displacement have not been done, it appears that the more comprehensive the school approach to tackling bullying, the less opportunity there is for another bully to rise up.

Bullies

Many of the European and Scandinavian studies concur that bullies tend to be aggressive, dominant and slightly below average in intelligence and reading ability (by middle school), and most evidence suggests that bullies are at least of average popularity.27 The belief that bullies "are insecure, deep down" is probably incorrect.28 Bullies do not appear to have much empathy for their victims.29 Young bullies tend to remain bullies, without appropriate intervention. "Adolescent bullies tend to become adult bullies, and then tend to have children who are bullies."30 In one study in which researchers followed bullies as they grew up, they found that youth who were bullies at 14 tended to have children who were bullies at 32, suggesting an intergenerational link.31 They also found that "[b]ullies have some similarities with other types of offenders. Bullies tend to be drawn disproportionately from lower socioeconomic-status families with poor child-rearing techniques, tend to be impulsive, and tend to be unsuccessful in school."32

In Australia, research shows that bullies have low empathy levels, are generally uncooperative and, based on self-reports, come from dysfunctional families low on love. Their parents tend to frequently criticize them and strictly control them.33 Dutch (and other) researchers have found a correlation between harsh physical punishments such as beatings, strict disciplinarian parents and bullying.34 In U.S. studies, researchers have found higher bullying rates among boys whose parents use physical punishment or violence against them.35

Some researchers suggest that bullies have poor social skills and compensate by bullying. Others suggest that bullies have keen insight into others' mental states and take advantage of that by picking on the emotionally less resilient.36 Along this line, there is some suggestion, currently being explored in research in the United States and elsewhere, that those who bully in the early grades are initially popular and considered leaders. However, by the third grade, the aggressive behavior is less well-regarded by peers, and those who become popular are those who do not bully. Some research also suggests that "[bullies] direct aggressive behavior at a variety of targets. As they learn the reactions of their peers, their pool of victims becomes increasingly smaller, and their choice of victims more consistent."37 Thus, bullies ultimately focus on peers who become chronic victims due to how those peers respond to aggression. This indicates that identifying chronic victims early on can be important for effective intervention.

A number of researchers believe that bullying occurs due to a combination of social interactions with parents, peers and teachers.38 The history of the parent-child relationship may contribute to cultivating a bully, and low levels of peer and teacher intervention combine to create opportunities for chronic bullies to thrive (as will be discussed later).

Incidents of Bullying

Bullying most often occurs where adult supervision is low or absent: schoolyards, cafeterias, bathrooms, hallways "Olweus (1994) found that there is an inverse relationship between the number of supervising adults present and the number of bully/victim incidents."40 The design of less-supervised locations can create opportunities for bullying. For instance, if bullying occurs in a cafeteria while students vie for places in line for food, line management techniques, perhaps drawn from crime prevention through environmental design, could limit the opportunity to bully. A number of studies have found that bullying also occurs in classrooms and on school buses, although less so than in recess areas and hallways. Upon greater scrutiny, one may find that in certain classrooms, bullying thrives, and in others, it is rare. Classroom bullying may have more to do with the classroom management techniques a teacher uses than with the number of adult supervisors in the room.

Other areas also offer opportunities for bullying. The Internet, still relatively new, creates opportunities for cyber-bullies, who can operate anonymously and harm a wide audience. For example, middle school, high school and college students from Los Angeles' San Fernando Valley area posted website messages that were

…full of sexual innuendo aimed at individual students and focusing on topics such as 'the weirdest people at your school.' The online bulletin boards had been accessed more than 67,000 times [in a two-week period], prompting a sense of despair among scores of teenagers disparaged on the site, and frustration among parents and school administrators…. One crying student, whose address and phone number were published on the site, was barraged with calls from people calling her a slut and a prostitute.41

A psychologist interviewed for the Los Angeles Times remarked on the harm of such Internet bullying:

It's not just a few of the kids at school; it's the whole world…."Anybody could log on and see what they said about you....What's written remains, haunting, torturing these kids.42

The imbalance of power here was not in the bully's size or strength, but in the instrument the bully chose to use, bringing worldwide publication to vicious school gossip.

Victims of Bullying

- Most bullies victimize students in the same class or year, although 30 percent of victims report that the bully was older, and approximately ten percent report that the bully was younger.43

- It is unknown the extent to which physical, mental or speech difficulties, eyeglasses, skin color, language, height, weight, hygiene, posture, and dress play a role in victim selection.44 One major study found "the only external characteristics...to be associated with victimization were that victims tended to be smaller and weaker than their peers."45 One study found that nonassertive youth who were socially incompetent had an increased likelihood of victimization.46 Having friends, especially ones who will help protect against bullying, appears to reduce the chances of victimization.47 A Dutch study found that "more than half of those who say they have no friends are being bullied (51%), vs. only 11 percent of those who say they have more than five friends."48

Consequences of Bullying

Victims of bullying suffer consequences beyond embarrassment. Some victims experience psychological and/or physical distress, are frequently absent and cannot concentrate on schoolwork. Research generally shows that victims have low self-esteem, and their victimization can lead to depression49 that can last for years after the victimization.50 In Australia, researchers found that between five and ten percent of students stayed at home to avoid being bullied. Boys and girls who were bullied at least once a week experienced poorer health, more frequently contemplated suicide, and suffered from depression, social dysfunction, anxiety, and insomnia.51 Another study found that adolescent victims, once they are adults, were more likely than nonbullied adults individuals to have children who are victims.52

Chronic Victims of Bullying

While many, if not most, students have been bullied at some point in their school career,53 chronic victims receive the brunt of the harm. It appears that a small subset of six to ten percent of school-age children are chronic victims,54 some bullied as often as several times a week.† There are more chronic victims in elementary school than in middle school, and the pool of chronic victims further shrinks as students enter high school. If a student is a chronic victim at age 15 (high school age), it would not be surprising to find that he or she has suffered through years of victimization. Because of the harm involved, anti-bullying interventions should include a component tailored to counter the abuse chronic victims suffer.

† These figures are based on studies in Dublin, Toronto and Sheffield, England (Farrington 1993). Olweus, however, in his Norwegian studies, found smaller percentages of chronic victims.

Several researchers suggest, although there is not agreement, that some chronic victims are "irritating" or "provocative" because their coping strategies include aggressively reacting to the bullying.55 The majority of chronic victims, however, are extremely passive and do not defend themselves. Provocative victims may be particularly difficult to help because their behavior must change substantially to lessen their abuse.

Both provocative and passive chronic victims tend to be anxious and insecure, "which may signal to others that they are easy targets."56 They are also less able to control their emotions, and more socially withdrawn. Tragically, chronic victims may return to bullies to try to continue the perceived relationship, which may initiate a new cycle of victimization. Chronic victims often remain victims even after switching to new classes with new students, suggesting that, without other interventions, nothing will change.57 In describing chronic victims, Olweus states: "It does not require much imagination to understand what it is to go through the school years in a state of more or less permanent anxiety and insecurity, and with poor self-esteem. It is not surprising that the victims' devaluation of themselves sometimes becomes so overwhelming that they see suicide as the only possible solution."58, †

† A handful of chronic victims make the leap from suicidal to homicidal thoughts. Clearly, access to guns is also an issue.

In the United States, courts appear open to at least hearing arguments from chronic victims of bullying who allege that schools have a duty to stop persistent victimization.59 It has yet to be decided to what extent schools have an obligation to keep students free from mistreatment by their peers. However, early and sincere attention to the problem of bullying is a school's best defense.

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Bullying in Schools

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.