Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Responses Using Civil Actions Against Property Page 2

Types of Property-Related Civil Remedies

Real-property rights relate to land and land uses. These can include such diverse rights as: (a) ownership, (b) the ability to transfer the property or to build on it, (c) the enjoyment of particular aspects related to it (such as a certain amount of relief from noise), and (d) the possession of it for business or residential purposes. Each of these rights is constrained, regulated, and protected in a variety of ways, and these differ across jurisdictions. Four general sources of authority for civil remedies have been identified: statute, subordinate legislation, contract, and tort.7 Here, statutory and other legislative and regulatory sources of authority (such as local ordinances and codes) and leasehold agreements (generally the right to occupy property) are highlighted.

The civil protections of these property rights provide legal remedies for their breach. Civil remedies do not necessarily include recovering money damages following a legal judgment favoring one party over another. Instead, they can force someone to correct a breach of a law, legal agreement, or a legally recognized right. Actual legislation in this area, however, may contain criminal law penalty components as well as civil remedies. These criminal penalties are often used when third parties fail to respond to the civil-remedy incentives for altering criminal-opportunity places and situations (see, e.g., “Anti-Slum Packet” in the box on page 26).

This section describes some basic terms that are used in property-related civil remedies, provides some examples,† and sets out some of the advantages and disadvantages of their use. These descriptions are purposely general, as the exact meaning of the regulatory scheme or civil action will be determined by the law in a particular jurisdiction. Because the law in your jurisdiction needs to guide your decision making, you should include government attorneys in the planning process when you are considering using civil remedies to address crime and disorder problems.

Civil remedies can be difficult to understand because, unlike penal codes, they do not easily fit within a strict hierarchical structure. Table 1 on page 10 gives short-hand descriptions of the civil remedies discussed in this section as a simple guide to the basic remedies each action provides.‡

† Additional examples are provided in the table in Appendixes C and D.

‡ Table B1 is set out in Appendix B to guide you in setting out the particular features of each of these civil remedies in your jurisdiction.

Table 1. Shorthand descriptions of some property-related civil remedies

| Code enforcement | Landlord/owner | Enforces health and safety rules |

| Zoning | Landlord/owner | Limits activities and structures to particular areas or locations |

| Nuisance abatement | Landlord/owner (usually) | Returns to (or seeks to achieve) quiet enjoyment |

| Eviction | Tenant | Removes the tenant |

| Trespass | Uninvited persons | Removes the non-tenant |

| Civil injunction | Various | Orders someone to do or stop doing something immediately |

| Receivership | Landlord/owner | Gets someone else to manage the property |

| Condemnation | Landlord/owner | Locks it up and tears it down |

Code Enforcement

Code enforcement is one of the most common civil prevention incentives used to address crime and disorder. It refers to the legal action taken by an enforcement body in response to a violation of one or more municipal health and safety codes, such as those related to building construction, building conditions (e.g., fire and safety and nuisance-control), and the operation of a business (e.g., a liquor store). Different agencies often control the enforcement of different regulatory codes; hence, the need for cooperation and coordinated responses among these agencies. For example, police and code inspectors may cooperate to inspect and issue breach notices for derelict or abandoned buildings suspected of being used as drug houses or providing a place for noisy parties for teens. One of the advantages of code enforcement is that it is based on statutes or ordinances that can be printed and distributed to those whose property is being regulated or inspected.

When there is a violation or breach, it often relates to noise, rubbish, or safety. Owners can be compelled to act to make their premises comply with the standards set out in the code. A civil injunction may be issued that requires them to deal with these problems (see “Civil Injunction” on page 22).8 Owners can be called on to secure their buildings, clean up litter, improve the physical environment, and evict tenants suspected of drug involvement (or other violations of the terms of their leases). The code enforcement aspect is the “stick,” but the “carrots” can vary from continued operation to increased revenues and safety for employees, as well as patrons and local residents. The ultimate stick for enforcement of licensed premises that sell alcohol, for example, is license revocation,9 in effect “capital punishment” for alcohol-sales outlets.10

Code enforcement initiatives against alcohol-related crime and disorder often focus on one aspect of the problem, such as excessive alcohol consumption, overcrowding, high noise levels, or lack of control over entry and exit to the venue or the vicinity. The police and code enforcement agencies often develop these initiatives in cooperation with the local club and bar owners.

A comprehensive review of aggression-prevention schemes in bars and pubs failed to find that there was one set of implementation approaches—or one set of measures—that succeeded in all situations.11 Nevertheless, code enforcement has been found to be part of an effective set of measures, reducing crime or aggression—at least in the shorter term (see Table D1 on page 55)12—although not uniformly so.13 The researchers who carried out the comprehensive review stressed, however, that enhanced enforcement (by police and regulatory agencies) has to continue past the lifetime of particular initiatives.14 This highlights the need for patience and a continued commitment by those involved in an initiative to make sure that success is not short-lived.

Effective code enforcement does not just involve having officials conduct code inspections. For example, regular police enforcement and a variety of code enforcement inspections (i.e., fire code and alcohol and gaming checks) of a nightclub were used initially in Burlington, Ontario (Canada).15 These had little effect on the crime problems at the site. It was only after two major disorder events by unruly patrons occurred that these problems were adequately addressed. The community (including police, regulators, adjoining businesses, and local residents) set up a number of different measures to control movement of cars and people within and around the club venue, including enforcement of health, safety, and licensing codes (see Table D1, Appendix D, on page 55).

Street Sweeping, Broadway Style: Revitalizing a Business District from the Inside Out

Place: Fort Howard District, Green Bay, Wisconsin

Civil remedies used: Liquor license regulations, municipal ordinances, and trespass law

Scanning:

- An inner-city business area had high crime, litter, and broken bottles.

- People were living on the streets, often drunk and disorderly.

Analysis:

- Police analysis identified 20 individuals as being involved in most of the complaints.

- Police found that neighborhood residents and business leaders had lost faith in the police to manage the problems.

Response:

Police spearheaded a community effort, strongly enforcing public ordinances on open

intoxicants and gaining the cooperation of liquor store and bar owners in denying alcohol to habitually intoxicated people (among a range of other tactics).

Assessment:

Four years after introduction of the POP initiative and introduction of community police officers, there was a 65 percent reduction in total police calls and a 91 percent decrease in demand for rescue services to handle injuries resulting from assaults.

Business in the area boomed.

Source: Green Bay Police Department (1999)

Zoning

Zoning refers to the governmental regulation of property uses on a long-range basis, particularly as part of long-term land-use planning.16 These regulations—which can apply to general areas (hence “zones”) or to location-specific land uses—include limits to the sizes and types of structures built on land and whether the property can be used for residential, commercial, industrial, or other particular kinds of purposes. Zoning is also used to limit when businesses in an area can be open. One type of exception to a zoning restriction is a conditional use permit, which is given by the regulatory body when certain conditions are met; this type of permit is generally limited in scope to a particular property.17 Mixed-use zones permit several different uses to occur in the same zone.

Zoning laws can be used to prevent a range of illegal activities by limiting the types of legal (and potentially illegal) activities—from alcohol consumption and sales, to dancing and having rave parties—that are permitted in particular areas. Some communities have restrictions on the number or types of businesses in a given block. Other communities restrict certain business types to one well-defined area to allow for concentrated police surveillance and enforcement. Many localities, including Boston, Massachusetts; Seattle, Washington; and Dallas, Texas, have passed zoning laws to restrict the location of adult-oriented activities considered to be generators of crime and neighborhood disorder.18

Both zoning ordinances and conditional use permits are commonly used to control alcohol sales. In California in the mid-1980s, zoning and conditional use permits were used to limit the placement and operation of alcohol-sales outlets following research evidence of a relationship between sales (and use) and public nuisances and crime.19 They have also been used to require alcohol establishments to be a certain distance from public places, such as parks or schools. The rationale for these types of restrictions is that there exists a causal link between alcohol availability and traffic crashes and assaults in particular settings.20

In Scottsdale, Arizona, zoning, liquor licensing, and security plans are explicitly linked. The online “Liquor License Packet” explains that liquor licensing and conditional use permit requests for the property (if needed) are to be submitted at the same time—and the body that reviews conditional use permits (the city council) can make recommendations to the state liquor licensing authority.21 This packet also details a series of rules related to different types of licensed premises. For example, bars, cocktail lounges, and after-hours establishments must have a management and security plan that is “created, approved, implemented, maintained, and enforced” for that business at the same time that the business applies for the liquor license.22 Thus, the suitability of the location is assessed in a public hearing and the rules of operation are linked to the granting of the license.

A discussion of factors to consider when developing new zoning regulations to address crime and disorder problems is beyond the scope of this guide. However, zoning changes (even those meant to stimulate business investment and help revitalize a local area) can lead to crime and disorder problems for that local community.23

Zoning & Liquor Licensing Regulations

Places: One community in northern California, one in southern California, and another in South Carolina

Problem identified through research on links between alcohol outlet location and crime problems. No single problem place was identified nor were particular cities or towns identified.

Responses/Interventions:

- Implemented zoning requirements related to distance between alcohol outlets and public places

- Reviewed licenses

- Restricted alcohol access for special events (licensing changes)

- Trained servers

- Police set up: (a) on-site stings for responsible service (no alcohol sold to the intoxicated), (b) stings for under-age drinkers, and (c) checkpoints

- Used breath-testing devices

Outcomes—Declines in:

- Hospital assault cases in experimental sites

- Rates of nighttime motor vehicle crashes (no decline in daytime vehicle crash rates)

- Monthly rates of DUI vehicle crashes

- Average quantities of alcohol consumed per occasion and average number of drinks per occasion (both self-reported measures of binge drinking)

Key factors:

- Community involvement

- Responsible serving practices

- Limiting under-age access

- Increased actual and perceived risk of enforcement of drunk driving

- Community restrictions on alcohol access

Source: Holder et al. (2000)

Nuisance Abatement

Nuisance abatement refers to a legal action to change a situation in which a person is being deprived of his or her right to “quiet enjoyment” by some existing condition, or by actions being carried out by another person, group, or business.24 Community partnerships can be particularly useful here if the law in your jurisdiction allows their direct involvement in bringing abatement actions.

Abatement statutes to discourage drug dealers were first implemented in Portland, Oregon, in 1987.25 By 1992, 24 U.S. states had passed statutes specifically designed to control drug activities on private properties.26 A number of these were based on old “bawdy house” laws designed to curb prostitution.†

† You may want to check your jurisdiction’s case law and statutes for the terms “bawdy houses,” “houses of ill repute,” and “disorderly houses” for additional prohibitions on nuisance activities, particularly if your jurisdiction has not updated or revamped its codes recently.

Abatement and eviction notices have been used hand-in-hand to address drug crimes in housing. Abatement actions focus on the property holder while eviction actions focus on the leaseholder or renter, but sometimes it is necessary to provide notice of potential abatement actions to induce the owner to act against the tenant (or, in at least one case, against the management company27).

Abating a nuisance problem often includes these steps or stages:28

- Local government becomes aware of nuisances through the activities of their own agencies (such as the police) as well as through complaints by others (such as apartment building residents or neighbors).

- Inspections may be conducted by a range of actors including building, health, electrical, plumbing, and fire inspectors.

- If the local regulatory authority is satisfied that a nuisance exists at a property, it must issue an abatement notice against the person responsible (usually the property owner), consisting of a letter or a public notice in a newspaper or a notice posted on the property.

- An abatement notice will stipulate that the nuisance is prohibited and that it needs to be rectified.

- It can specify steps that need to be taken to meet the terms of the notice together with a time limit, such as asking property owners to take action against drug dealers who are operating on their premises.

- In addition to a demand for remedial action, the notice may warn of the possible closing down, or the confiscation of properties, that are being used for the crime.

- Failure to comply with an abatement notice without being able to provide a reasonable excuse can be a criminal offense.

- However, it is up to your municipality’s prosecutor to show that the excuse is not reasonable.

The first warning is typically enough to leverage owners to take action. In fact, early research on the use of abatements in the 1990s found that civil suits were filed in fewer than 5 percent of abatement actions in cities that initiate warning letters to property owners.29

Some abatement laws permit private citizens (including property owners) to directly issue notices to the responsible party (usually the property owner) and then, if the nuisance still continues after a given time, apply to the court for relief. Private citizens may also be able to bring a nuisance complaint directly to the attention of the court and request an abatement notice. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for example, citizens themselves filed civil lawsuits against drug nuisance property owners.30

In 2007, Los Angeles County began using nuisance abatement lawsuits against both the property owners and the specific gang members who allowed or created a nuisance at a particular property.31 In these cases, both sets of parties were named in the suits, which were termed “gang property abatements.”

An intervention at an apartment complex in San Diego, California included many Section 8 U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) -sponsored units.32 When the police were unable to gain HUD’s assistance with the owner to replace what appeared to be a corrupt management company, they looked to bring an abatement action, based on a claim that the owner or the management company had facilitated the nuisance activity there. If that failed, as a last resort, the police would have asked the California Board of Realtors to revoke the management company’s business license. The police did not need to take this action, however, since the possibility of abatement was sufficient to motivate the owner to act quickly.

Abatement measures, and the potential use of further actions consistent with the nuisance problem, can be used to pressure owners to act against crime on their properties, even if they are not the perpetrator. When used against drug crime, abatement procedures can offer property owners legal authority and support to evict drug criminals, or those holding the lease on the property if they are not themselves offenders.33 The mere threat of abatement proceedings can encourage owners to screen their prospective tenants more completely.34

In addition, abatement is much less expensive than other types of litigation, because there is little risk of having to pay the defendant’s legal costs if the claim is unsuccessful.35 Because of the complexity and effort (compared to voluntary cooperation) of nuisance abatement procedures, however, you may want to approach the landlord directly first before you bring legal action against him or her. This might also speed up the compliance process.

Turning Around a “Troubled Building”

(Known to Police for Assaults and Drug-related Activity)

Place: Seattle, Washington

Civil remedy used: Chronic Nuisance Property Ordinance

Problem place: Building with assaults and drug-related activity

Ordinance:

- Passed by the City Council in November 2009

- Defined a chronic nuisance property as one where certain crimes, drug-related activities, or gang-related activities occur three times within a 60-day period or seven times within a 12-month period

Collaboration partners:

- Police department and the city attorney’s office

Implementation:

- Building was declared a “chronic nuisance” by the city

- Police met with the owner to discuss the issues

- Owner agreed to cooperate

- Owner entered into a “correction agreement” with the city to remedy the problems on the property

Outcome:

Following the intervention, no 911 calls were logged at the building over the next year.

Source: Holmes (2012)

Eviction

An eviction is a civil action brought to remove someone from a property where the person’s possession of that property has been deemed to be illegal, such as when the tenant has violated the terms of the lease. In these situations, the tenant (and his or her possessions) can be removed and he or she can be locked out of the property. This removal action will often be the last action used when other measures have been unsuccessful in ameliorating the crime or disorder conditions. This civil action is also sometimes referred to as “an unlawful detainer action.”36

Other actions having a more limited effect on the tenancy that can be brought by landlords against tenants include waste actions (a civil action rooted in the common law). A waste action asserts that the tenant is doing something to destroy the current or future use of the property.37

In parts of the United Kingdom additional measures, other than eviction, are used as a way of monitoring tenant behavior to help deal with nuisance and disorder in public housing. Demotion is a short-term measure used in England and Wales that changes the conditions of the tenancy. It gives tenants a less secure tenancy (in terms of its protections against possession proceedings), normally lasting for a year.38 It can be used against tenants for anti-social behavior (essentially nuisance behavior). Closure refers to the action of locking out tenants for a period of three months following nuisance or disorder behavior that results from drug use or drug supplying.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988 was passed by the U.S. Congress, allowing civil remedies (and other, criminal penalties) to be used to address drug crimes. In 1990, the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development made funds available to public housing authorities to combat drug and crime problems. Drug Elimination Programs (DEP) combined police enforcement, drug treatment, drug prevention, youth and gang outreach, community organizing, integrated health and social service agencies, and tenant mobilization projects in an ambitious and complex intervention to control drug use and drug selling in public housing.39

Note however, that other programs in New York City40 and Knoxville, Tennessee,41 were not found by the evaluators to be successful (see description of these programs in Appendix C).

As part of a partnership approach, police can use private security, the public housing administrators and property managers, local government authorities, real estate agents, and community members (such as other residents of the building or complex) to assist in identifying problem tenants and providing information about illegal activities.42 Administrators can enforce tenancy agreements and evict tenants who are involved with, or providing housing to those involved with drug manufacturing, sales, or use.

The New York Narcotics Eviction Program allowed for the leaseholders to be evicted if evidence could be produced that they were aware that their rented premise was being used for drug dealing, even where the drug dealers were not the official tenants.43 This tenancy situation was often the case, and the eviction was possible even if the dealers were using the tenant’s property without their consent. The crucial element was that the tenant was aware of the use. In Los Angeles and other locations in California, there was a pilot program to address drug crime using an unlawful detainer statute. Under this California law, property owners were able to assign their rights to file unlawful detainer actions to city attorneys. Due to funding and reporting issues, however, this pilot program was inconclusive.44

The possibility of eviction provides landlords and administrators (tenancy place managers) with a powerful incentive to use to gain tenants’ compliance with regulations. Eviction can be used as part of a range of measures and is usually the most severe civil consequence for a tenant. However, it is not always part of a successful campaign. It may move the problem elsewhere or affect the innocent.

Manhattan District Attorney’s Narcotics Eviction Program

Place: New York, New York

Civil remedy used: N.Y.S. Real Property Actions and Proceedings Law §715 (from 1987)*

Problem places: Public housing with problems related to drug sales and use

Measures used:

- Tenants were evicted by landlords who were provided with proof of illegal drug activity in their premises and were given legal support.

- Witnesses were able to tip off police anonymously, without having to testify in court.

- Landowners who did not comply with a notice to evict a tenant could face $5,000 in fines.

Outcome:

Between June 1988 and August 1994, the program evicted drug dealers from 2,005 apartments and retail stores.

* Originally, this law was enacted in 1868 to abate “bawdy house” activity, with §715 amended in 1947 to include “any illegal trade, business or manufacture.”

Source: Finn (1995)

Trespass

In its simplest form, civil trespass “involves an infringement on the use of one person’s property by another person who has no authority or legitimate right to infringe on such person’s use”45 and is enforced by the wronged party, while criminal trespass involves the violation of a statutory prohibition and is enforced by the police. Civil law rights are set out by statute or may be incorporated in tenancy agreements.

Trespass Program for Use in Housing Common Areas

Place: Portland, Oregon

The Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) contracted with the county sheriff’s office to implement a trespass strategy (involving both civil and criminal components) as part of a multi-pronged approach to managing “gang activity” on a public housing estate.

Problem place: Public housing estate with “gang activity”

Measures used:

- The county sheriff dedicated special patrol officers (“Safety Action Team” or SAT) to the housing estate.

- SAT officers were made the agents of the property owners so the officers could enter private property to enforce rules even when violations were not crimes. This allowed the officers to expel non-tenant gang members (as trespassers) and arrest any who returned.

- HAP also began strictly enforcing its leases and evicting girlfriends (of the gang members) who had unauthorized gang member guests.

Problem with the initial scheme:

The prosecutor’s office could not prosecute its initial criminal trespass cases due to problems with the terms of the existing leases.

Changes in the program structure suggested by the prosecutor’s office:

- Obtain lease addenda putting HAP in charge of common areas for the purposes of enforcing trespass laws.

- Agree upon rules non-tenants had to follow in common areas.

- Delegate exclusion authority to the SAT.

Outcome:

Letters permitting the SAT and Portland police officers to enforce trespass laws were signed. Officers were then able, under the law, to enforce exclusion of non-tenants violating behavior codes and arrest gang members who returned, prosecuting them for criminal trespass.

The strategy was considered a success because gang members were eliminated from the estate common areas within 18 months.

Source: Hayden (2007)

Unlike civil remedies that seek to change landlords’ or tenants’ behavior, anti-trespass provisions of tenancies or statutes have the advantage of targeting the controls on those present on the property that may be creating crime opportunities or carrying out illegal activities but who are not subject to tenancy controls. A 1996 study reported that an estimated 70–90 percent of those arrested in public housing communities were intruders or trespassers, not residents.46 This same research found that trespass prevention programs had been successfully conducted in Denison, Texas; Greensboro, Georgia; Clearwater, Florida; and Tampa, Florida.47

Two main pathways for assertion of civil trespass rights in residential situations have been and can be used. First, police can encourage landlords and others to assert their rights to bring a civil action themselves.48 Second, landlords can use an affidavit to authorize others (e.g., police) to enforce these rights for them. In addition to allowing law enforcement officers to ask trespassers to leave an area, this last pathway can also result in a criminal prosecution if those asked to leave return. Criminal prosecutions can also occur if police find contraband on trespassers.

In the case of civil trespass in public housing, the police can encourage stakeholders, such as public housing management, private security, resident patrols, and resident groups, to use their rights against non-tenant trespassers, depending on the tenancy agreements in place. These trespass law initiatives may be reinforced through the creation of resident “passes” and identification programs for authorized tenants. This approach is most effective when access to the property is controlled by the presence of on-site security guards and access control points, because trespassing rules are difficult to enforce in an open or open-access community.49

Another program that involves having the police act as agents for the landlords is the Trespass Affidavit Program (TAP) in New York City. In New York County (Manhattan), TAP requires landlords to register for the program, post signs throughout the buildings that say “Tenants and Their Guests ONLY,” provide the police with an up-to-date list of all tenants and keys to the buildings, and allow the police to conduct “vertical patrols” in the building.50 Not only is there a possibility of a stiffer enforcement mechanism with these transferal of rights agreements, but they may also increase the likelihood that any actual enforcement will occur.

One major disadvantage of the use of trespass enforcement can be the lack of support from the local community. This can occur if there is not adequate notice of the program or when there is a perception of over-enforcement. Legal challenges to trespass affidavit programs may be based on claims of disparate enforcement on the basis of race or ethnicity or assertions that police are conducting stop-and-frisk procedures without an adequate legal basis or adequate oversight.51

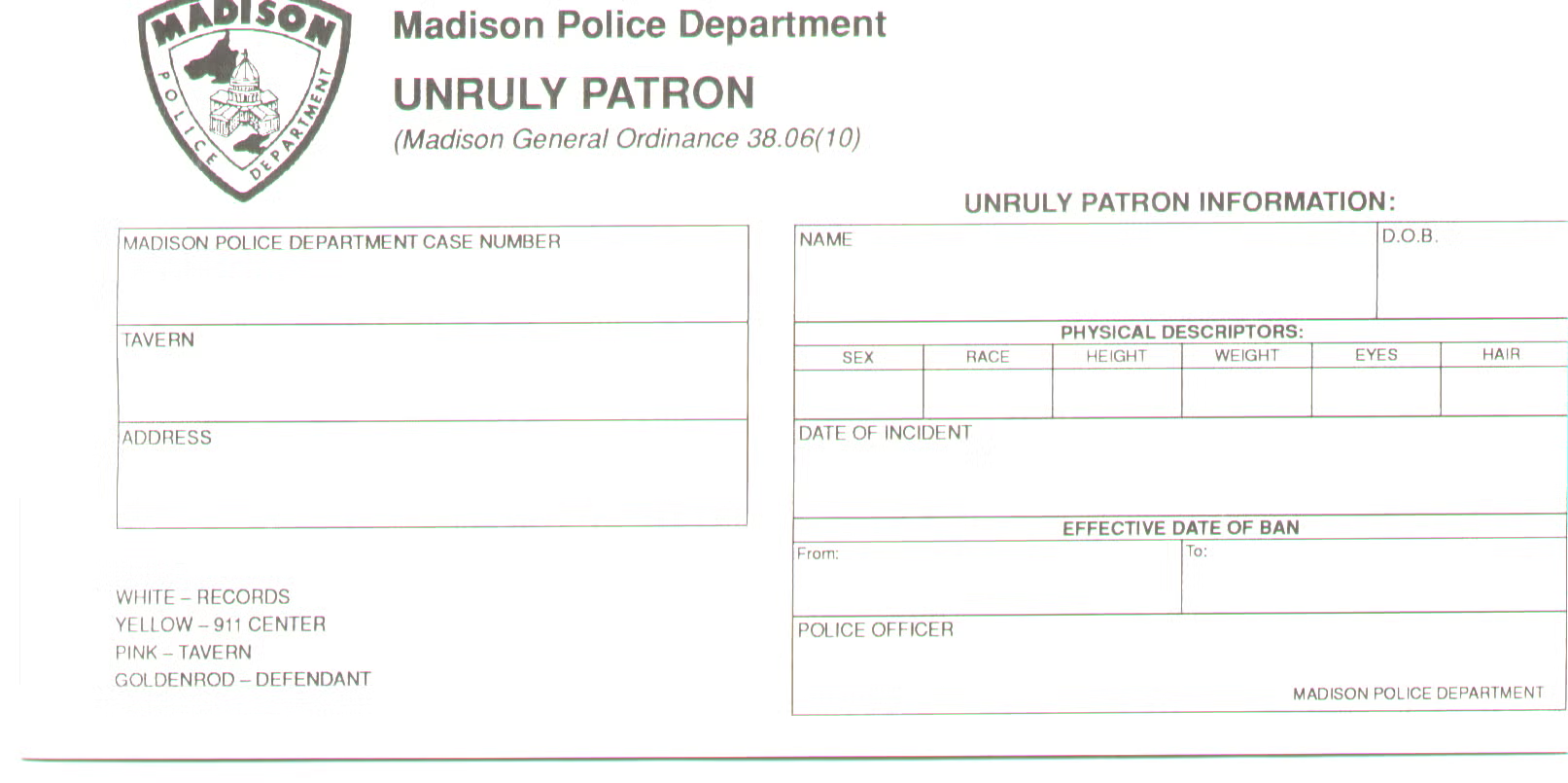

Criminal trespass actions have also been used to address alcohol-related crime and disorder problems. For example, criminal trespass warnings have been used to keep troublemakers away from a late-night venue after they have been arrested there. Criminal trespass was used to help control assaultive behavior in a particular country-western nightclub in Texas that had been experiencing a high volume of police activity for alcohol-related disorder and crime. Texas law allowed a person to be arrested for criminal trespass if they had been “warned away” from a location in the presence of a peace officer.52 A similar practice is used in Madison, Wisconsin, in which persons deemed “unruly patrons” can be temporarily banished from a licensed establishment (see Figure 1).53

Example of an "Unruly Patron" form from Madison (Wisconsin) Police Department. It has boxes for the case number, the tavern and address as well as information about the unruly patron including name, date of birth, physical descriptors, the date of the incident, effective date of ban and the police officer's name.

Figure 1. Example of “Unruly Patron” form from Madison (Wisconsin) Police Department

Civil Injunction

A civil injunction is the general term for a court order that seeks to force someone to perform an action or to stop someone from doing something that causes harm (or has the potential to cause harm). Property-related injunctions can be focused on stopping a person, group, or organization from carrying out behavior that prevents others from enjoying a property-related right they have, or can order an owner to remedy nuisance conditions. These injunctions can be either temporary or permanent, with permanent injunctions usually being issued following a court hearing in which both parties receive notice of the hearing and have an opportunity to respond. The issuing of a civil injunction can be part of a larger civil proceeding, such as nuisance abatement, where it can be used to stop a business from operating in a way that contributes to the alleged nuisance activities.

Courts may grant injunctions in nuisance abatement cases if the nuisance is severe enough or the harm needs to be addressed more quickly.54 Breaches of court orders can result in a contempt ruling, which can be a criminal offense and result in a jail term or a fine. Courts may also order property closed—the most common sanction—and sometimes they may order the property sold at auction.

Temporary injunctions, depending on their breadth, can gain the attention of the targeted party and induce them to act to prevent the loss of income or some further civil action.

As with any civil remedy used against a party who is allowing crime or disorder conditions to exist on their property, these orders can be ignored by the targeted party unless there are further consequences to their issuance.

Receivership

Property is considered to be in receivership when a court has transferred its management to a third party, such as a bank or administrator. This may be done with severely deteriorated buildings to allow the receivers to repair the structures, and force the owners to cover the costs.55 When used as part of a crime-prevention initiative, the court may have previously found that the owner did not respond adequately to a court order following a nuisance abatement action or other civil action.

The example from Maricopa County, Arizona, in the “package of civil measures” section (see page 25) describes how receivership can be used as part of a civil-remedy crime-prevention initiative.

The potential loss of revenue to landlords who are forced to give up their profits in a receivership may be sufficient to change crime and disorder conditions, although some property targeted by police may not generate a large amount of income. This could make it difficult to find a competent receiver if the remedy is used, rather than just seen as a possibility.

Condemnation

This action is brought by a court signifying that the building on a parcel of property is not habitable—or, as in one case, the cost of repair is higher than the cost of replacement and it is no longer a place to be lived in.56 Access to the building will be restricted; it will be “boarded up” prior to, or as an alternative to, demolition. This remedy is usually seen as a last resort when addressing crime problems.

Condemnation and boarding up of properties can be highly effective in certain circumstances. In other circumstances, it can be very controversial and lead to worsened conditions in the short term—if residents are uncertain where they will live or existing social controls are disrupted.

Chicago Housing Authorities (CHA) Anti-Drug Initiative (ADI)

Place: Three high-rise housing developments in Chicago, Illinois

(Final phase of initiative discussed here)

Federal regulations required housing authorities to demolish public housing properties where the costs of repairs exceeded the cost of replacement.

Initial problems identified: Crime, violence, and disorder, including drug sales and use, primarily by young residents

Activities: (see also Table C1, Appendix C)

- Increased level of housing services (better security and increased cleaning and repair) related to initiative

- Redevelopment effort unrelated to ADI initiative

- Identification and demolition of severely distressed public housing (unrelated to ADI initiative)

- Prosecution of gang members (unrelated to ADI initiative)

Outcome:

- Gang wars resulted from loss of leaders in powerful gang

- In the short term, the demolition worsened conditions (e.g., changes occurred in staffing at buildings not demolished)—which were measured by resident perceptions of their quality of life

- Condemnation and demolition of scattered buildings disrupted key gang territories, causing new conflicts and rising fears among residents that they might be left homeless.

Source: Popkin et al. (1999)

Provisions requiring landlords to vacate buildings following nuisance abatement actions were used more successfully in Joliet, Illinois. In one enforcement project, after repeated attempts to gain landlord cooperation, a group of apartments were ordered closed and tenants were required to vacate the premises and move elsewhere. A new owner made the needed changes. Tenants were able to apply for an apartment.57 In another Joliet Police Department project, at the request of the police, the city council passed an ordinance requiring landlords to cooperate with police once they had been notified of criminal activity on their property (as part of a nuisance abatement effort).58 If the landlord failed to comply, then he or she would be forced to vacate the property, leaving it empty.

The condemnation process can remove buildings that are no longer habitable or are dangerous for area residents or passersby. The possibility of having to vacate a building can be used as another tool for gaining landlord cooperation and may encourage action at an early stage, so that the property does not need to be vacated, boarded up, or torn down.

It has been unclear and difficult to predict the success of a program involving the securing of abandoned buildings, due to the difficulties involved with measuring impacts and the limited evidence base.59 Also, this type of program can present other problems in the short term because of its high degree of disruption for both offenders and local residents.

Other Civil Measures

Negligence

Individuals and businesses can be held civilly liable (for damages incurred) as a result of their failure to meet a duty of care to others. These general principles of liability (and the possibility of their application) can be usefully applied in the context of property-related crime and disorder prevention if they force land owners, landlords, and businesses to alter property conditions conducive to these offenses.60 While “negligence” is the more general legal term for these types of actions, the term “civil liability” is often use to describe lawsuits brought against property owners in this context.

Dram Shop Provisions

In addition to the ordinary principles of negligence related to businesses, statutes may exist in your jurisdiction that create a special type of “civil liability” focused on a legal duty of care applicable to alcohol establishments (or “dram shops”). These provisions create a legal liability for harms caused by patrons whom the shops served after they were already intoxicated. The economic incentives and disincentives related to this liability risk have been used as part of the group of incentives behind interventions to limit alcohol-related problems, such as highlighting the need for training about responsible serving practices.61

Package of Civil Measures

As is apparent from the discussion of particular civil remedies, legislation may incorporate a number of these civil remedies into one package of possible responses. One example that demonstrated this approach was used in Maricopa County, Arizona, to persuade landlords to deal with suspected repetitive criminal activities by their tenants by focusing on nuisance abatement as the primary measure (see “Anti-Slum Packet” box on page 26).

“Anti-Slum Packet”

Place: Maricopa County, Arizona

Civil Remedy: Arizona Law (A.R.S. §§12-991-12-999)

The Maricopa County Attorney produced a set of documents to encourage local residents and neighborhood associations to use a criminal abatement statute (A.R.S. §§12-991-12-999) to eliminate suspected drug houses from their areas. The statute was broad enough, however, to include in the definition of a “nuisance” “residential property that is regularly used in the commission of a crime” (A.R.S. §12-991).

Although this was called an “anti-slum packet,” most of the material in it focused on the process and tools for bringing a civil action to address crime rather than disorder or physical deterioration. The statute requires property owners to take certain steps to deal with repetitive crime that is occurring on their property—whether used for residential or commercial purposes. If, after receiving notice of the repetitive crime problem, the owner does not take steps to rectify the problem, then the city prosecutor can seek a civil injunction requiring him or her to do so. If, after an investigation, the county attorney finds that the owner has violated the civil injunction, then the owner can be prosecuted for a felony. The statute also calls for the issuance of a temporary restraining order, which is served on the legal occupant of the property and includes a right to a hearing in court. The statute also allows the court to issue a permanent civil injunction, appoint a temporary receiver to manage or operate the property, award expenses, and impose a civil monetary penalty. The property may also be closed. Notice of the abatement action must be filed with the county recorder and the action applies to future owners.

Local residents were encouraged to assist in this process by:

1. Observing and monitoring the activities they see occurring at the rental property

2. Using standardized reporting forms to document this information

3. Searching county property records to identify who owns this property

4. Mailing a letter to the owner describing the activities, the owner’s responsibilities, and the potential consequences of a failure to act to deal with these activities

5. Sending copies of these documents to the local police department for further investigation

The statute (A.R.S. §12-991) allows not only the attorney general or any city or county attorney to sue, but any resident of the county or city affected by the nuisance can also bring the action in court.

The website packet included model letters for police departments and local residents or neighborhood associations to use, as well as guidelines and forms for recording crime incidents and newspaper clippings highlighting the potential consequences of a failure to act.

Another statute (A.R S. §§33-1901–33-1905) discussed in this packet from the Maricopa County Attorney deals with the registration of property ownership, the definition of a “slum property” as property meeting specific conditions that pose a danger to public health and safety, and the appointment of a temporary receiver to address these problems.

Source: Maricopa County Attorney (n.d.)