Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Tools Understanding Theft of 'Hot Products' Page 5

Analyzing Hot Products Problems

Factors Affecting Which Products Are Hot

Once you have detected a theft-related problem, think about theft from the perspective of what is stolen rather than from simply where it is taken. Consider the variation in risk for particular types of products and think about your particular local context and how that is likely to affect what is available, what is hot, and what is not. Within general product types, there is considerable variation across the following factors, which are discussed below:

- Product life-cycles

- Specific product types and models

- Types of crime committed

- Theft methods

- Historical time periods

- Countries or regions

Product Life-Cycles

Considering the life-cycle stage of a product and the theft volume of it will help you anticipate whether there is likely to be a surge or a decline in the theft of that item (and indeed, more generally). For example, if an item that is currently frequently stolen is entering the market-saturation phase of the product life-cycle then it is likely that the theft of this item will soon decrease, regardless of efforts to reduce the theft of this type of item. In contrast, if a frequently stolen product is at an early stage of the product life-cycle, then you should consider what might be done to prevent the theft of this type of item.

Note that it is dangerous to assume that product life-cycles will follow the same trend at the same time in different places. For example, 1990s car models in the United States were being stolen to be resold in Mexico in the 2000s where they were still desirable. There might also be a delay between a peak in sales of a new product and a peak in levels of theft.† Moreover, life-cycle time scales vary across products. For example, while changes to “white” goods may be slow, updates to the specifications of tablet computers and mobile phones occur on an annual basis, which rejuvenates the legitimate (and stolen-goods) market.

† Unfortunately, a lack of freely available systematic sales data makes detailed analysis of this delay difficult to undertake. However, there is evidence of a delay between increases in the market price of copper and subsequent levels of theft which confirms that such delays are highly possible (see Sidebottom et al. 2011).

Specific Product Types and Models

Not all mobile phones, for example, will carry the same risk of being stolen. Similarly, there will be large variation in the types of cars that are commonly stolen. Certain makes or models of a particular product might be more or less appealing to a thief in a variety of ways. For example, newer high-value cars might be particularly valuable and enjoyable. However, such vehicles may be less available (both in terms of sheer numbers and levels of security) and less concealable (a high-value new vehicle model will be more likely to be noticed) than older, ordinary vehicles.

Types of Crime Committed

Different crime types tend to have different associated hot products. Consider the following examples:

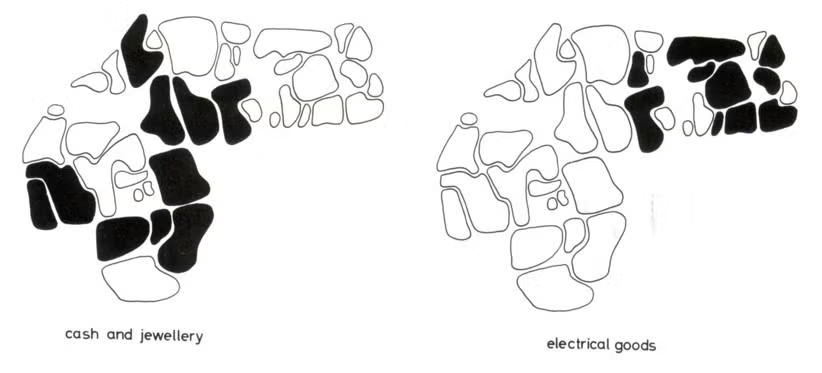

- For thefts from residences, such as burglary, household items are most at risk, but patterns can vary. As an illustration, in two bordering areas of Northampton, United Kingdom, different items were targeted, with cash and jewelry taken downtown and electrical goods targeted in the suburbs.32 Furthermore, in the downtown area, burglars tended to be on foot and burgled older homes, whereas in the suburban area they travelled by car and targeted newer homes.

- For theft from retailers such as shoplifting, the most targeted items are consumable goods. Analysis can identify which stores are driving the problem and where within the store problem items are located.

- For thefts from person such as street robbery, thieves tend to target the contents of handbags and wallets. The time of day can also affect what products are targeted in street robberies: for example, laptop computers might be targeted in the early evening as people leave work, while handbags and wallets may be targeted at later hours when people are out for the evening.

- For theft from vehicle, both personal items and car parts can go missing. One local crime wave targeted headlights from Nissan cars: the headlights were of high quality, easily removable, and easily installed in older Nissans. Also for this crime, laptops and handbags left in view, and satellite navigation systems are common targets.

Theft Methods

Compared to thefts in which numerous items are stolen, certain models of phone appear to be targeted when stolen in isolation.33 Additionally, for thefts in bars, different items have been found to be stolen when an entire bag is taken compared to when single items are stolen out of the bag.34

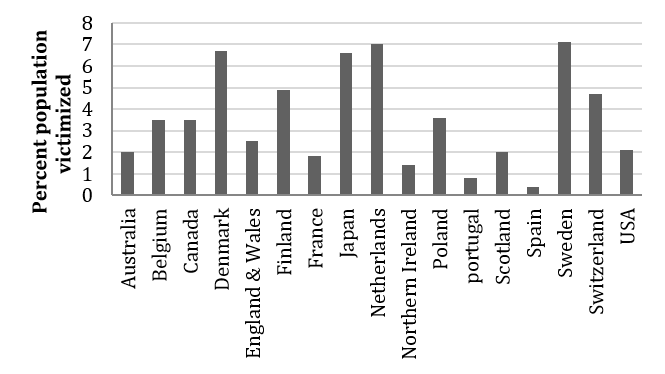

Figure 1. Prevalence of bicycle theft across selected countries

Historical Time Periods

Trends also vary over time. For example, it is unlikely that theft of domestic animals and timber, particularly rife in 19th century England, will feature in the list of the top ten items stolen in the United States in 2012.35 What is CRAVED in one time period may well not be in another. The Australian study discussed above provides an example of specific changes in hot products, but to illustrate just how quickly things can change consider that the first iPad was only introduced in 2010.

Countries or Regions

Trends vary by country or region too. For example, as shown in Figure 1 bicycle theft varies greatly by country, being particularly rife in Japan, Sweden, Denmark, and Holland. These are countries where the availability of bikes is very high and there are cultural reasons for high bike usage and, therefore, greater exposure to theft.36

When you understand the complex nature of the problem you can better develop tailored preventive actions. Example 2 on page 26 illustrates how understanding what is hot can be a powerful prevention tool.

Example 2: Using Hot Products Analysis to Tailor Prevention Efforts

During the analysis phase of a U.K. burglary reduction project (conducted in 1998) researchers established that two items were predominantly stolen: cash (49 percent of offenses) taken from the cash-operated electricity meters popular at that time, and audio-visual equipment (33 percent of offenses). As a result of this insight, the removal of pre-pay electricity meters was a significant component of the prevention strategy. The researchers estimated that, with the opportunity to steal cash reduced, burglary volume declined by more than 50 percent in the treatment area relative to the rest of the police division.37

Example 3 shows the value of examining hot products in the context of a particular theft problem, in this case theft of items from construction sites.38 Here, undertaking careful crime analysis of hot products was the key to working out the best response strategy.

Example 3: Hot Products Taken in Construction Site Thefts in Charlotte, North Carolina

A building boom in Charlotte, North Carolina, led to sharp increases in the number of kitchen appliances stolen from houses under construction. A long-term POP project was undertaken by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department to address this. A detailed analysis of security practices and risks of theft was made for 25 builders operating in one of the police service districts north of the city. This led to the recommendation that the installation of appliances should be delayed until home owners took up residence, effectively removing the theft targets.

Of the larger building firms, only 12 agreed to experiment with this approach for six months, though. Systematic checks by the police indicated that builder compliance varied but findings indicated that delayed installation was an effective policy. Appliance theft declined in the district and there was no evidence of displacement of thefts to surrounding districts.

Source: Clarke and Goldstein 2003 (text adapted from original source)

In some instances it might not be readily apparent why targeted products are CRAVED. To illustrate, in one study low-value items such as incense, analgesics, decongestants, baby milk, bath salts, and drinking straws were found to be frequently stolen from U.S. supermarkets. None of these are conventionally CRAVED items on their own, but it turns out that in combination they can either be used to produce a drug high, were useful in a drug production process (particularly methamphetamine), or helped users recuperate after drug use.39 When seemingly mysterious hot products appear, try searching the Internet, government databases, or consumer indexes for news accounts and further information that might explain how the product is used in some type of criminal activity.

Further, it should be recognized that it might not be the products themselves that are the only driver of crime patterns. This is why exploring the local context is important. As an example, in one community CDs and DVDs were going missing from a retailer. Further analysis revealed that this occurred between 3:30 PM and 6:00 PM, when the local school children visited the shop to play video games. The solution was to deny access to the games between these hours rather than to focus exclusively on securing the hot products themselves.

Assessing the Risk Potential of Products

A useful starting point is a scoring system that scores the risk associated with products prior to their launch, or indeed at any point during the product’s lifespan. Tools to do this were developed as part of a project for the U.K. Department of Trade and Industry.40 These checklists (see Appendix A) help analyze how hot or secure a product is likely to be. Checklist 1 uses the CRAVED framework and provides a simple scoring system to assess how hot a product is likely to be. Checklist 2 flips the analysis and can be used to assess the strengths of the product’s security features. Bearing in mind that most products have at least one element which is CRAVED, the advantage of this numeric scoring component is that it can help distinguish those that are particularly at risk from those that are moderately so.

Measuring the Theft Risk of Hot Products

It is important to consider whether a product should be considered as hot if it has a high volume of theft, a high rate of theft, or both. For example, it should not be surprising that mobile phones are stolen in high volumes given their general availability. However, a high theft volume does not necessarily indicate a high rate per item at risk. The theft rate of a particular product may be low even if that product is frequently stolen. For example, the theft risk per items in circulation may be lower for mobile phones than for 3D televisions.

It would be ideal to calculate theft rates routinely for every product considered, but in reality this is difficult as data on product sales are commercially sensitive and hence difficult to obtain.

Determining the number of products available (the denominator in the theft rate) is therefore often difficult and may require some creativity in assessing product theft rates. For example, to estimate the potential numbers of opportunities for bag theft in bars, the number of seats in an establishment has previously been used to estimate capacity.41 To properly assess mobile phone theft risk, you should treat thefts for which multiple items are stolen as special cases because for these crimes the phone may just have been an incidental theft target rather than a deliberate one.42

Some additional methods for assessing the risk associated with particular products suggested

include the following:

- Determine whether some products are more likely to be stolen on their own than with other products. Products stolen on their own are hotter products.

- Approximate denominators using national or regional product data (e.g., aggregated data on car sales or vehicle registrations may exist for the state).

- Use survey or observation data that you have collected yourself or that has been collected for other purposes (e.g., a bicycle user survey to estimate the number of different bicycle types).

- For analyses that examine patterns for specific crimes at particular places, use proxy denominators such as the number of people passing through an area for thefts from persons, or the percentage of all burglaries in which a certain type of item was taken.

- Determine the contribution of hot products to the percentage of total thefts. This can be done on a product-by-product basis. This will give an idea of the impact of that product on theft in the community.

Using Police Data

There are two basic approaches to analyzing hot products: 1) product-led analysis involves searching the data for occurrences of a particular product believed to be targeted; and 2) data-led analysis where no assumptions are made about which products are hot and the aim of the analysis is to establish which ones are.

Police crime records include what was stolen during an offense either in a fixed-field (multiple-choice) format or as free text. How difficult, precise, and reliable your data analysis will be is affected by a number of factors, including the following:

- Whether the data is computerized

- Whether the relevant data can be searched by computer

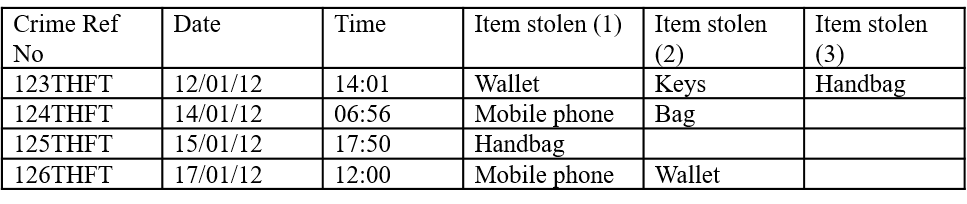

- The level of detail required in the police report (e.g., product type, make, model, serial number, value, quantity, and/or description) (see Figure 2)

- Whether victims know detailed product information

- Whether reporting officers record product data completely and accurately

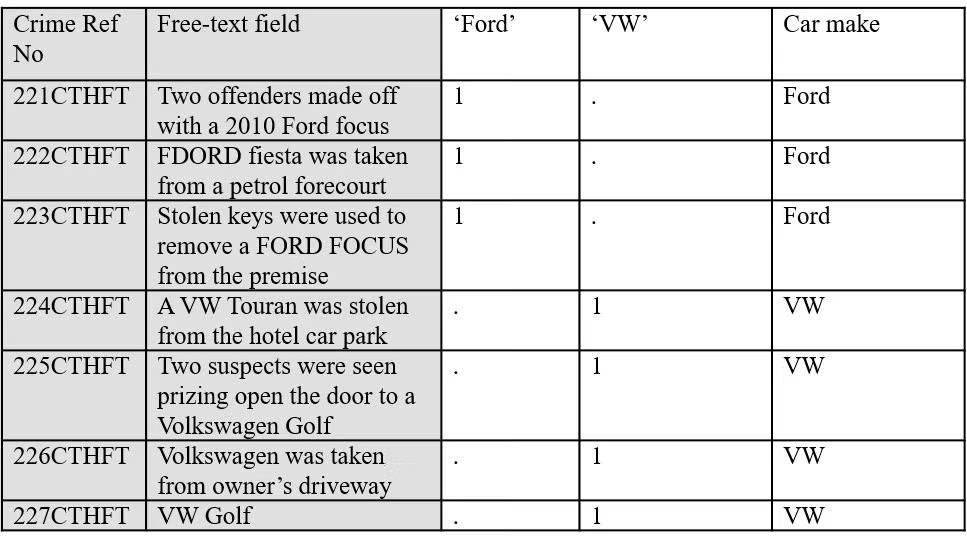

Figure 2. Sample police incident report property section

Fixed-Field Analysis

The analysis of fixed-field data is easier to undertake than for free-text data, although it still requires some effort to produce a useful analysis.

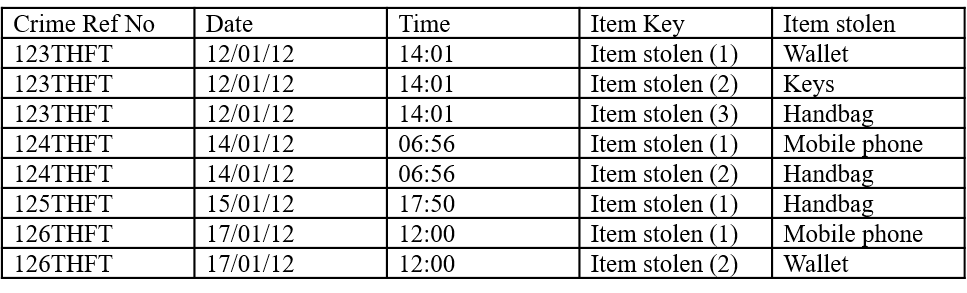

When recorded crime data are collated into a single file for the purposes of analysis, each crime incident is often stored in a single row of the file. This means that the items stolen will be listed across multiple columns, which may not make the analysis easy. The reason for this is simply that the units of interest—for which descriptive statistics are sought—will be the items stolen rather than crimes.

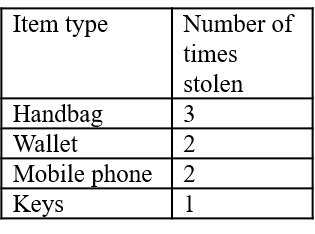

In order to do the analysis where the data are stored in this way, consider reorganizing them as shown in Figure 3.† Once transformed, simple frequency commands or pivot tables can be used to summarize the number of times that different products have been reported as stolen (see Table 5). For a data-led analysis, it is now clear which products are stolen in the highest volumes and for a product-led analysis, where the product of interest lies within the range of products stolen.

† The ‘transform’ command in SPSS, or the ‘transpose’ command in Excel® can help you do this.

Figure 3. Transforming the data for hot product analysis

Table 5. Frequency distribution of stolen items

Table 5 represents a very basic level of analysis, but provides a good idea of what is stolen. One problem with fixed-field data is that only those types of products that are included in the classification will be included in the analysis. This is problematic if a new hot product is not included in the categories available. Additionally, data recorded in a fixed format may not include information beyond a basic indication of the product type: the make, model, or other pertinent information may not be recorded.

Free-Text Analysis

You may need to conduct a more detailed analysis of what is stolen by analyzing free text, including that found in narrative reports. Even here, existing computer software can make the process more efficient. For example, there are procedures that can be used to search for the occurrence of a particular character string (e.g., a product name) within your data. In the case of car theft, you might be interested in identifying both the make (the manufacturer such as Nissan) and the model (such as Pathfinder) of vehicles taken. To do this, for each crime record that includes the loss of a car, you will probably need to create extra fixed fields of information for the make and model of vehicles stolen. It is helpful to begin this process by generating a list of the major manufacturers, makes, and models. An Internet search should facilitate this.

Table 6. Producing a ‘car make’ variable from free-text field data

Next, you can use software searching functions to identify those records in which the names of these makes and models occur. Keep in mind that names may be misspelled (e.g., ‘FORD,’ ‘ford,’ or ‘Frod’) and that some vehicle names might actually refer to something other than the vehicle (e.g., “Ford” is a common last name; and names such as “Dispatch,” “Modus,” “Partner,” and “Cruiser” also commonly appear in police reports with no reference to the cars). Table 6 is one example of how you might go about the process. The first two new variables flag the presence of a particular make of car and the final column shows a combined “car make” variable.

The first two columns can be created using software searching functions.† For instance, we may search for the word ‘Ford’ in our free-text fields and return a ‘1’ in a new variable labeled ‘Ford’ if that word is found. The final ‘car make’ column can be produced using ‘if’ statements. So, we add the word ‘Ford’ in our new ‘car make’ variable if there is a ‘1’ in the individual ‘Ford’ variable, and ‘VW’ if there is a ‘1’ in the ‘VW’ variable. At this point, we might sort the cases according to our new ‘car make’ variable. Scrolling to the end of the file is likely to reveal cases where the car manufacturer has not been identified using these search procedures. Often the best way to deal with these is to code them manually and then re-sort the data.

† For example, the ‘CHAR.INDEX’ command in SPSS.

Other Data Sets

In lieu of or in addition to using your own police data, existing research studies can provide information on which products are hot. These include the car theft index† and the mobile phone theft index which identifies the makes and models most frequently stolen. While useful, they are updated sporadically, which means that they can become out of date, are only available for certain intervals of time, and typically reflect national level trends that might not match local ones.

† The most up-to-date published versions of the U.K. car theft index can be found at the U.K. Home Office website (www.homeoffice.gov.uk). The Highway Loss Data Institute website is a useful source of data on car theft in the United States.

If addressing theft from retailers, loss-prevention data is a useful information source. Many retailers do not report theft under a certain dollar amount to police because they just consider it shrinkage. Therefore, if using reported crime data alone, take care because numbers may be very skewed.

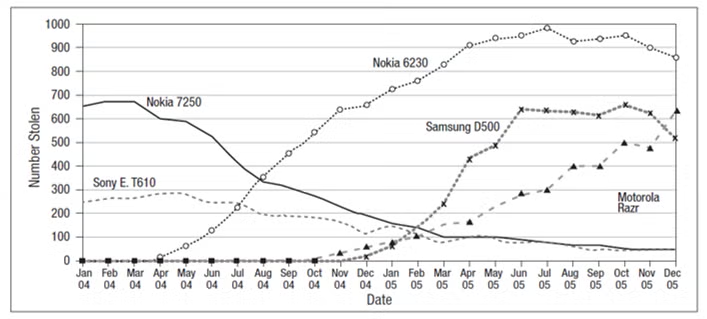

Analyzing Variations in Theft of Hot Products

Once data have been coded, you can examine how the theft of particular products varies over time, space, by type of offense, or modus operandi. Useful analyses would perhaps begin by examining variations over time. For example, you might examine monthly variation in the theft of a particular product over the last few years, and see how such variation compares to other similar products. Figure 4 illustrates the value of such analysis for the theft of mobile phones.43 The figure illustrates how this can help identify at which product life-cycle stage a particular product is.

Figure 4.Theft careers of mobile phones

Figure 5. Using hot products to tailor preventive efforts

The maps below depict the neighborhoods in Northampton, United Kingdom, that were particularly affected by thefts of different product types in burglaries: cash and jewelry were targeted in one area; electrical goods in the other.44

There will also be value in examining spatial patterns. Particular products may be stolen in some neighborhoods more than others. For example, one testable hypothesis is whether the theft of certain products is more common around second-hand goods markets. Figure 5 provides an example of how patterns may vary geographically. Profiling spatial patterns by time of day or year may also be useful. Understanding such patterns will help you distinguish between theft problems that might appear on the surface to be related, but which in fact are not. Usually, different problems call for different responses.

Measuring the Effectiveness of Responses to Hot Products Theft Problems

Hot-products data can also be used to measure the effectiveness of responses to theft problems. For example, if tamper-proof bicycle stands are placed in an area to control bicycle theft, then relative to another area without them, bicycle theft in this area should decline, even if other theft types in the area are unaffected. If cafés or bars provide secure storage facilities for customers’ personal property, this should lead to a reduction in snatch thefts, thefts out of bags, and thefts of bags from under tables. Measuring product-specific theft reductions, as opposed to overall theft reductions, increases confidence in understanding and demonstrating what it was that caused the reduction.