Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Responses to the Problem of Street Racing

Your analysis of your local problem should give you a better understanding of the factors contributing to it. Once you have analyzed your local problem and established a baseline for measuring effectiveness, you should consider possible responses to address the problem.

The following response strategies provide a foundation of ideas for addressing your particular problem. These strategies are drawn from a variety of research studies and police reports. There is little published research about street racing; most of what is known is drawn from police practice. Several of these strategies may apply to your community's problem. It is critical that you tailor responses to local circumstances, and that you can justify each response based on reliable analysis. In most cases, an effective strategy will involve implementing several different responses. Law enforcement responses alone are seldom effective in reducing or solving the problem. Do not limit yourself to considering what police can do: give careful consideration to who in your community shares responsibility for the problem and can help police better respond to it.

General Considerations for an Effective Strategy

1. Enlisting community support for addressing the problem. Broad-based coalitions that incorporate the interests of the community are recommended. A combined effort will maximize the effects of responses and enhance the likelihood of success. The involvement and support of public officials, citizens, and business owners will be essential for the success of most, if not all, of the specific responses listed below.

Enlisting community support might include using members of a police Explorer post, citizens' police academy, senior citizens' groups, merchant association, and so on to report racers' activities to police.29 Community support might also come from those who provide racers with their equipment, including shops selling high-performance car parts, and who are at risk for being burglarized for these parts. Although these shop owners may not wish to cooperate, if so inclined, they can be of considerable assistance in informing the police about racers' illegal activities.

2. Educating and warning street racers. Street racers can be informed about the dangers and legal consequences of racing, as well as police enforcement intentions. Among the media you can use are street racing websites (on which they commonly announce past and future events, host chat rooms, and have message boards), police agency websites, newspapers, television, radio, and personal contacts with street racers. A publicity campaign about the problem and enforcement actions has been central to many efforts to combat street racing problems. Performance shop owners also might be asked to provide customers information about existing laws and potential penalties for racing.

4. Encouraging others to exercise informal control over street racing participants. You may identify certain groups, organizations, or individuals who have the potential to exert significant influence over the behavior of street racing participants. For example, if street racing participants are high school students, school administrators might be persuaded to suspend or revoke the parking privileges of students identified as participants in or spectators of street racing incidents. Insurance companies, which also have an interest in the problem, may be persuaded not to pay claims for damages if the claimant was participating in racing.† Parents of street racing participants, properly educated about the dangers of street racing, may be encouraged to get more involved in controlling their children's behavior.

† The San Diego Police Department trains insurance investigators in matters concerning racing (Sloan, 2004) .

Specific Responses to Street Racing

Enforcement

5. Enforcing ordinances and statutes. You should review existing ordinances and statutes to determine whether police have adequate enforcement authority. Laws likely to be enforced against drivers include racing/reckless driving, driving under the influence of alcohol or drugs, and driving with suspended/revoked licenses. In some jurisdictions police officers and vehicle emission enforcement agents jointly conduct smog equipment inspections on street racing vehicles, issue the owner a citation if the equipment was disconnected or modified, and even order the vehicle removed from the street until it is brought into compliance with the law.32 Officers might also attempt to identify people in the emissions testing industry who issue fraudulent emission certificates for the illegally modified vehicles.33 Drivers should be checked for proof of insurance and vehicle registration. Officers can work with automotive experts to identify street racing vehicles that have been illegally enhanced or altered, or have mechanical defects. Enforcement against non-drivers might include violations for trespassing on private property of adjacent businesses, obstructing traffic (if standing in the roadway), or aiding in a speed contest (for people acting as starters for races). Dedicated race patrol teams may be necessary for concentrated enforcement during peak racing times.34 Enforcement of curfew laws might also reduce the numbers of juveniles present at racing venues.

Following are some examples of how many police agencies have been aided with newly enacted ordinances and statutes in their attempts to prevent and address street racing:

- In California, a conviction for engaging in a "speed contest" (defined as a motor vehicle racing against another vehicle or being timed by a clock or other device) consists of a fine up to $1,000 plus penalty assessments, up to 90 days in jail, or both. The perpetrator's license may be suspended or restricted for up to six months, and a police officer may impound a vehicle when the driver is arrested for engaging in a speed contest, for reckless driving, or for demonstrating exhibit of speed (for example, peeling or screeching of tires due to hard acceleration). A vehicle can be impounded for up to 30 days, and it costs the offender $1,500 to retrieve it. Persons who aid or abet any speed contest (such as a person who flags the start of the race or places a barricade on the highway) can be charged with a misdemeanor.35

- The State of Texas enacted harsher penalties for street racing in 2003. The new law made street racing a more serious violation, punishable by up to six months in jail and a $2,000 fine for both drivers and passengers; and up to a $4,000 fine and one year in jail if the driver was intoxicated, had an open container of alcohol in the vehicle, or had previously been convicted of the same offense. Spectators can be cited and fined up to $500 as well.

- Street racers can be charged with engaging in a speed contest and reckless driving, fined up to $1,000, and sentenced to six months in jail in Reno, Nevada. Spectators within 200 feet of an illegal street race can also be arrested and fined up to $200. The driver's vehicle can be impounded and storage fees assessed at $50 per day.36

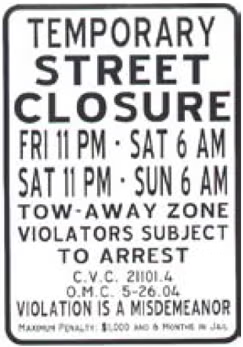

- The City of Fremont, California banned all traffic between 10 PM and 6 AM on 10 roads popular with street racers and allowed police to impound the vehicles of both drivers and spectators.37

- The City of Santee, California made it unlawful for any individual to be a spectator (within 200 feet) at an illegal speed contest, or where preparations are being made for an illegal speed contest; violators are subject to fines of up to $1,000 and six months in jail.

6. Impounding and/or forfeiting vehicles used for street racing. Vehicles may be impounded and a fee assessed in order for the owner to retrieve the vehicle under an ordinance when the driver is arrested for engaging in a speed contest, for reckless driving, or for demonstrating exhibit of speed (e.g., peeling or screeching of tires due to hard acceleration). A vehicle forfeiture ordinance may be enacted to declare a vehicle a nuisance and it can be permanently seized if it was used in a race or exhibition of speed and the driver has a prior conviction for certain serious driving offenses (such as reckless driving or evading officers).

- The City of San Diego was among the first to pass a vehicle forfeiture ordinance, in 2003. A vehicle will be declared a nuisance and permanently seized if it was used in a race or exhibition of speed and the driver has a prior conviction for certain serious driving offenses (such as reckless driving or evading officers).38

- The City Council of Los Angeles soon followed San Diego's example, also approving vehicle-forfeiture legislation. The vehicles are auctioned off and the money deposited into the city's general fund. Furthermore, police in both the City of Los Angeles and Los Angeles County can arrest spectators on a misdemeanor. In July 2003, the first man to be convicted under the Los Angeles law was sentenced to 18 months' probation and 10 days community service.39 The city uses state Bureau of Automotive Repair investigators to inspect vehicles suspected of being illegally modified by their owners; a city ordinance prohibits disconnection, modification, or alteration of pollution control devices, and cited drivers must return their vehicles to their original factory specifications.40

- The City of Stockton, California, also targeted offenders' vehicles rather than the drivers, relying on the aforementioned state statute allowing the police to seize for 30 days vehicles that were used in reckless driving incidents.41

7. Encouraging private businesses to adopt measures that will help address the problem. Owners and managers of popular street racing gathering places (where street racers meet and plan their activities, show off their cars, socialize, and the problems begin to occur) must be enlisted in efforts to discourage street racing activity. Among the helpful measures are: posting "no trespassing" signs and authorizing police to enforce them, limiting after-hours access, employing private security during weekends, and closing earlier.

Providing a Safe Alternative

9. Creating or encouraging racers' legal alternatives, such as relocating to a legal racing area. Several cities and counties have successfully addressed their illegal street racing problem by creating, either on their own or in collaboration with other organizations, a legal racing venue. This is intended to divert people to a safer racing environment, which allows racers to experience some of the positive aspects of legal drag racing—the fun, camaraderie, and excitement. Police can either align with an existing national program (for example, Beat the Heat, Racers Against Street Racing, the National Hot Rod Association) that encourages safe, legal, on-track racing, or implement their own local program.† Participant rules should be in place, such as racers must possess a valid drivers license and vehicle insurance, submit to vehicle safety inspections, and refrain from any use of alcohol at the event.44

† See the Redding ( California) Police Department street racing web page at www.reddingpolice.org/StreetLegalDrags/

Following are examples of such efforts:

- Beat the Heat is a national Cops and Kids community policing drag race program, which involves police officers in 30 states and two Canadian provinces. As an example, a police officer in Wewoka, Oklahoma (population 4,000) initiated the program. The officer races local men and women in his 1972 Chevrolet Camaro (with a 545-horsepower engine) at a local track. Teens can serve as honorary pit crew members for the Camaro.45 The program originated in 1984 with the Jacksonville, Florida, Sheriff's Department and has grown rapidly; in 1999, more than 1 million young people were given the message that they should go to tracks to race their cars instead of racing in the street.46

- Concerned about illegal street racing and the dearth of legal racing venues, automobile manufacturers, police officials, racetrack owners, racers, automobile parts manufacturers, and the media met in California in early 2001 and formed Racers Against Street Racing (RASR); this organization is becoming a countrywide phenomenon that is being tested in driver's education classrooms and consists of a curriculum and video. RASR addresses the realities of street racing, and informs students about local street racing laws and legal alternatives in local areas.47

- An officer in Redding, California obtained $4,000 from local businesses to help start a racing program, "Street Legal Drags," at a local drag strip in mid-2002. Soon there were more than 200 cars (drivers paying $10 to race) and more than 2,500 spectators (assessed $5 per carload). Signs are posted informing racers how to register their vehicles, proceed to the starting line, and leave the track after the race. The Redding police website explains the program and provides detailed instructions for participants. Participants must have a registered, insured, safety-inspected vehicle and a valid driver's license; and no alcohol is allowed on the premises.48

- Las Vegas, Nevada has Midnight Mayhem, Friday night amateur drag races from 10:00 PM to 2:00 AM at the local speedway's drag strip. The cost is $10 for drivers and $5 for spectators, and each night's activities include music, car shows, and other events for the 2,500 spectators and 400 drivers.49

Responses With Limited Effectiveness

10. Installing speed bumps. The installation of speed bumps can reduce or halt street racing, but they are hazardous to emergency vehicles and large trucks. Speed humps, on the other hand, which are more gradual than speed bumps, permit vehicles to cross them safely at the speed limit and create less risk to trucks and emergency vehicles.

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Street Racing

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.