Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Understanding Your Local Problem

The information provided above is only a generalized description of bicycle theft. You must combine the basic facts with a more specific understanding of your local problem. To enable you to design an effective response, you will likely need to analyze local data carefully.

Your local bicycle theft problem can take many forms, and you will need to determine the specific nature of the problem to produce an effective response. It may be limited to, or a combination of, thefts from in or around victims' homes; thefts from public spaces; or thefts from particular areas such as university campuses or transit hubs.

Knowledge of the location, facilities available, and types of bicycles stolen will aid in identifying conditions that might contribute to the problem. Clues as to how thieves steal bikes may be apparent from locks found at the scene of thefts, CCTV footage, and related offenses.

This knowledge can also help you identify who is committing the offenses, and why. For example, where the quantity of stolen cycles recovered is high, a high proportion of offenders are probably joyriders. Preventive efforts for such offenders will differ from those for offenders who sell bicycles on (acquisitive/volume offenders). Such analyses may be possible only if you systematically collect data (for example, it may be necessary to distinguish between burglaries in which bicycles are stolen and those in which they are not). Ensuring the systematic recording of bicycle thefts will allow for better analysis and subsequently better targeted responses to your local problem. Alternatively, you may need to collect or identify new data sources. For example, alongside observational research, consulting with bicycle theft victims may help to reveal specific problems that you would not otherwise identify.

Stakeholders

In addition to criminal justice agencies, the following groups have an interest in the bicycle theft problem and should be considered for the contribution they might make to gathering information about the problem and responding to it:

- Elected and appointed local government officials

- Community planning organizations

- Traffic engineering departments

- Street-furniture designers

- Bicycle clubs and networks (including bicycle theft victims)

- Bicycle and bicycle-part retailers

- Insurance companies

- Large employers

- Transport providers

- Large educational establishments.

Asking the Right Questions

The following are some critical questions you should ask when analyzing your particular bicycle theft problem, even if the answers are not always readily available. Your answers to these and other questions will help you define your local problem and choose the most appropriate set of responses later on.

The Nature of Bicycle Theft

- Are bicycle theft data recorded in a way that aids analysis of your local problem?

- What are the type and quality of locks being used?

- Are bicycles locked when stolen? If so, how?

- Does locking practice vary by location (e.g., at home and public spaces)?

- To what are bicycles locked? Are bicycles stolen from residential locations secured to anything at all?

- What happens to bicycles once they are stolen? Are they sold illegally? If so, who is buying them? Are they stripped for parts? Are they abandoned?

- What perpetrator techniques are common? Do they differ across locations?

- What current preventive measures are ineffective? (See "Measuring Your Effectiveness" below).

- How soon are recovered bicycles found?

- How damaged are recovered bicycles?

- How many bicycle thefts are unreported, and why?

- How concerned is the local community about stolen bicycles?

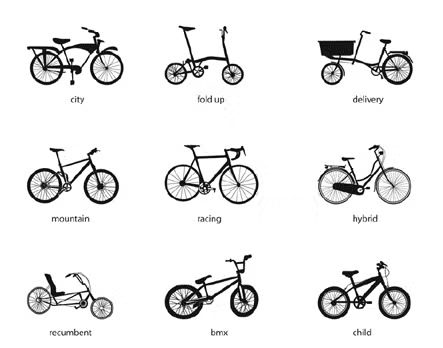

- What types of bicycles are thieves stealing (a standard typology such as the one below may help in answering this)?

Locations and Times

- Where is your local bicycle theft problem located? In the victims' homes? Workplaces? Certain streets? On-street vs. off-street parking? Risky facilities? General hot spots (such as downtown areas)?

- Where hot spots are identified, why are these locations at high risk of bicycle theft? Lack of secure parking? High levels of flyparking? A lack of capable guardians informed and empowered to act?

- Which places in particularly risky areas are at the greatest risk? On a university campus, for example, is it the gym? Library? Dormitories? Particular classroom buildings?

- How prevalent is flyparking at different locations? Are parking facilities sufficient for cyclist demand? Are parking facilities located in the wrong places?§

- What types of houses or apartment buildings do thieves target for bicycle theft? Detached or row homes? One-story, or two-story? Large or small apartment buildings? (Visual surveys of victimized houses and apartments will help you answer these and other questions.)§§

- Do theft rates vary across cycle-parking facilities? If so, how, and what factors might contribute?

- Which groups are the principal users of the facilities? Workers? Shoppers? Young people? Students?

- Is lack of natural surveillance (guardianship) a factor?

- Where are recovered bicycles found?

- When do thefts mainly occur (time of day, day of week, month)?

Are there local seasonal variations in bicycle theft?

§ For example, at London's Walthamstow train station, secure cycle-parking facilities were installed on a site on the opposite side of the train track to the ticket office. This was accessible only via a bridge and resulted in commuters' continuing to flypark their bicycles to railings outside the ticket office entrance, with the new facility being underused.

§§ Zhang, Messner, and Liu (2007) found that in the Chinese city of Tianjin, people living in row houses were less likely to be bike theft victims than those living in apartment buildings.

Offenders§

- What kinds of offenders are involved? Joyriders? Acquisitive/drug addicts? Professionals?

- What do you know about the offenders? Are they local?

- Do offenders tend to work alone? Does this differ by offender category?

- Do bike thieves know their victims?

- Do bike thieves operate in the same location?

Are stolen bicycles being sold in your local area?

§ See Problem-Solving Tool Guide No. 3, Using Offender Interviews To Inform Police Problem Solving.

Victims

- Whom does bicycle theft harm (e.g., cyclists, business owners)?

- What is known about bicycle theft victims (e.g., their routine activities, demographics, cycle use, prior victimization)? What forums are available to glean this information and engage with victims?

- What form of transportation do victims use after thieves steal their bicycles? Do they buy a new bicycle? Use a different form of transportation?

- Does victimization change a victim's cycle-related behavior? Locking practice? Parking location?

- Do cyclists see publicity regarding secure cycle practice? If so, where? Do they think current publicity is useful?

- Under what circumstances do thefts occur? Is victim behavior a contributory factor, such as leaving bicycles unsecured and visible/accessible?

Current Responses

- What types of bicycle-parking facilities are available? Are they maintained?

- Is there an active bicycle registration scheme? What percentage of reported stolen bicycles are registered?

- Is anything being done about abandoned bicycles (the "broken bike effect")?

- Is anything being done about flyparked bicycles?

- What proportion of stolen bicycles are recovered?

- What proportion of recovered bicycles are returned to their rightful owners?

- What proportion of offenses result in an arrest?

- What are the typical legal consequences for convicted bicycle thieves?

Measuring Your Effectiveness

Measurement allows you to determine to what degree your efforts have succeeded, and suggests how you might modify your responses if they are not producing the intended results. You should take measures of your problem before you implement responses, to determine how serious the problem is, and after you implement them, to determine whether they have been effective. All measures should be taken in both the target area and the surrounding area to provide you with control data against which to compare your intervention data. For more detailed guidance on measuring effectiveness, see the Problem-Solving Tools guide, Assessing Responses to Problems.

The types of measures considered will depend on the particular problem to be tackled and the type of intervention to be implemented. For example, if part of the aim of an intervention is to change cyclists' locking practices, then in addition to measuring what was implemented (process measures) and any changes in bike theft rates (outcome measures), a useful intermediate measure would be the degree to which cyclists' locking practices have changed as a result of intervention. If the locking practices do not change over time, then you cannot attribute any reduction in crime observed to locking practices. Only by measuring changes in this type of behavior would you be able to come to such conclusions and understand what it was that led to the (un)desired outcomes.

To measure potential success, you should establish the following measures.

Process Measures

- What was implemented?

- Where was it implemented?

- When was it implemented, and with what intensity (e.g., how many stands were installed, or how many bicycles registered with a registration scheme)?

- Which stakeholders were involved in implementation? Did they achieve their specified objectives?

- If publicity was used (e.g., to encourage cyclists to lock their bikes more securely), then how was the information communicated (e.g., posters, news articles, radio broadcasts)? How widely was it distributed?

Intermediate Outcome Measures

- Increased use of bike-parking facilities

- Degree to which any publicity used reached the target audience (e.g., measured by a cyclist survey relating to the implemented response)

- Improvements in cyclists' locking practices

- Reductions in flyparking

- Reductions in the number of unoccupied stands in public places

- Reductions in the number of abandoned bikes found in parking facilities

- Reductions in the number of calls to remove damaged or abandoned bikes

- Reductions in the number of damaged, abandoned locks

- Increased reporting of thefts to police (if bicycle theft is heavily underreported)

- Changes in perpetrator techniques

Some types of intervention may encourage cycle retailers to report useful information, and so you should consider changes in information flow when relevant. Although there may be no legal duty for retailers to contact the police about damaged or stolen cycles, they may be able to provide a rich source of data concerning your local problem, including who is stealing the bicycles or why they may be targeting particular types of bike.

Ultimate Outcome Measures

- Reduced theft reports to police

- Reduced theft reports to place managers (e.g., university officials or apartment managers)

- More favorable perceptions of safety/security among bike users

- Reductions in repeat victimization

- Increases in the number of bicycles recovered

- Increases in the number of recovered bicycles that are returned to their rightful owners

- Increases or reductions in the number of bicycles stolen in nearby areas (Bicycle theft may be displaced, causing a rise in nearby areas or facilities or, conversely, a diffusion of benefits may occur, whereby bicycle theft is reduced in surrounding areas or facilities)

- Improvements in victim perception of police handling of bicycle theft (measured by victim surveys in relation to implemented responses)

- Reduced value of reported stolen bicycles (which might indicate that more-valuable bicycles are being better protected).

One potential problem with using crimes reported to the police as a measure of the effectiveness of interventions concerns the underreporting discussed earlier. For example, it is possible that following police intervention or a publicity campaign, victims will be more likely to report crimes to the police. On the one hand, this is a good thing and will facilitate a better understanding of the crime problem. On the other, it may create the illusion that bicycle theft has increased, when the reality may be that it has not (it may even have decreased). Instead, the intervention activity has led to an increase in victims' willingness and likelihood to report crimes to the police. Two ways of examining this issue are as follows:

- Ask victims who report bicycle theft if they are aware of any interventions. If they are, ask if they would have reported the crime if they had not been. While imperfect, this approach may provide some indication of the extent to which an intervention has influenced reporting levels.

- Try to identify potential parallel reporting measures. For example, for some time before intervention (to establish a baseline reporting rate), it may be possible to conduct surveys in local bicycle shops to find out how frequently customers have mentioned that their bicycles (or cycle components) have been stolen. If you ask bicycle shop staff to record such information, then you may persuade them to keep details of reports made. Such an exercise may be beneficial for reasons other than the evaluation of interventions. For instance, it may provide useful intelligence on related criminal activity and, by demonstrating that police consider bike theft an important issue, enhance community relations.

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Bicycle Theft

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.