Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Responses Monitoring Offenders on Conditional Release Page 2

Overview of Community Supervision

Correctional supervision in the community is a contract between the offender and the court: The individual’s freedom is conditional, meaning that any behavior that violates certain rules can result in the revocation of community release and a return to incarceration. An offender can be conditionally released to community supervision for three reasons: pre-trial release/bail, probation, or parole (either mandatory or discretionary). Each of these groups is subject to different supervision conditions, and as such, the police can use different strategies to prevent reoffending among these different offenders.

Prior to detailing these strategies, it is imperative to first describe the problem. Importantly, changes in legislature and judicial practices have greatly impacted corrections populations. Many jurisdictions have removed the possibility for prisoners to earn their release, and many more offenders are being sentenced to incarceration (see Figure 2); this directly increases the number of offenders who will ultimately be supervised in the community, either through diversion or post-release supervision. With so many probationers and parolees, the communities absorbing these offenders must develop strategies to effectively prevent more crime.

Although criminal justice spending has grown over time, it has not matched the increased number of offenders being monitored in the community. Police and community corrections agencies are being required to do more with less; even though caseloads have risen and support for reentry services has diminished, the public still demands community safety. These constraints must be balanced by using practices that are demonstrated to be useful. Given the context the police must work in, the need for effective monitoring practices is greater now than ever.

Descriptive Statistics

Though there is no way to know how many actively offending individuals are on conditional release, we know that the number of people on probation or parole at any one time is quite high. At the end of 2010, nearly five million offenders (about 1 in 48 adults in the United States) were under conditional release (see Figure 3). Of the 1.6 million offenders in American prisons, the overwhelming majority (around 95 percent) will be returned to the community, at the rate of approximately 700,000 individuals per year.

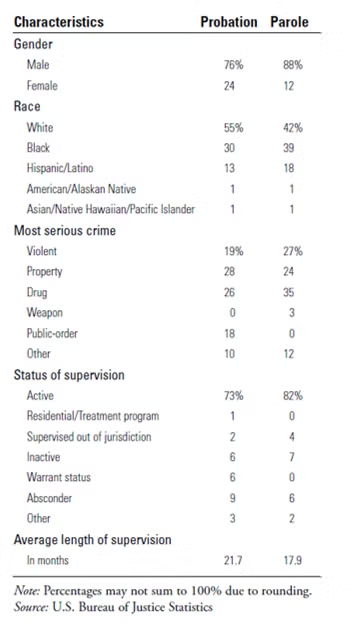

In 2010, the number of offenders under community supervision declined, following 30 years of increases. Of the 4,887,900 offenders on conditional release, probationers account for 83 percent of this total (see Table 1). Property offenders receive probation more often, while violent and drug offenders are a larger proportion of parolees. The average community supervision term is 22 months for probation, and 18 months for parole.

Table 1. Characteristics of offenders under community supervision, 2010

Rates of failure in probation supervision are much lower than for parole, although the raw number of offenders not completing the supervision term is higher for probationers. In 2010, nearly two-thirds of probationers satisfactorily completed the terms of their community sentence, while only 35 percent of parolees successfully completed their supervision. There is certainly room for growth, and some strategies are more effective than others; research consistently reports that recidivism is reduced when the emphasis of supervision is on service (risk reduction) as opposed to surveillance (risk control).1 Criminal justice agents can contribute to crime prevention by understanding and altering the characteristics that place offenders at a high risk for reoffending.

Goal Conflict

Police, courts, and corrections officials may have very different ideas of what success looks like for offenders on conditional release. These differences are important, because they reflect diversity in the goals that each agency has. Simply, interventions are usually judged by their ability to lower rates of recidivism; not so simply, how recidivism is measured affects what results are observed. There are two important and related points that readers should be aware of:

- First, there is a murky distinction between technical violations and official recidivism. Technical violations refer to when offenders break the rules of the supervision term (such as failing to seek employment or associating with a known gang member), while recidivism formally refers to those instances where offenders under community corrections sentences commit a new crime. Both can result in an arrest, although for different reasons. Technical violations of parole conditions accounted for more than one-third of all prison admissions in 2003, while only 10 percent of parolees returned to prison due to a new conviction.2 Similarly, nearly half of all jail inmates are on probation or parole at the time of their arrest.3 Thus, readers should appreciate the difference between the types of rearrest for community supervised offenders; one is due to a technical violation (like consistently showing up late for an Alcoholics Anonymous course) and one is due to committing a new crime (a breach of law regardless of the offender’s supervision status). It is important to note that many technical violations are unrelated to criminal propensity, especially when generic rules of supervision are broken.

- Second, like other patterns of behavior, small relapses are not a total failure (e.g., cheating on a diet or smoking one cigarette while trying to quit). The revocation of a probation or parole sentence may not be a good reflection of persistence in crime, as the rules that were violated may be inconsequential to offending. This is important, because short-term compliance may be a necessary precursor to more lasting behavioral change, especially when the conditions of supervision are carefully designed to address the factors that cause that individual to commit crime. Yet, desisting from crime is a gradual and cumulative process, so many outcomes should be used to measure success. The effectiveness of community supervision should be assessed by “intermediate” measures (such as stable employment and participation in treatment) in addition to “hard” outcomes (like convictions for new crimes). Though an individual may remain involved in crime, their level of offending may decrease substantially while under supervision. This can be used to promote additional change within the offender, until their criminal identity is entirely eliminated and full desistance is observed.

When criminal justice agencies define success and measure outcomes very differently, this can mean that the goals of different agencies conflict with one another. Police have the immediate goal of reducing a crime problem of interest, preferably in a period of months. Community corrections officials have the more distant goal of reducing offending; rehabilitation takes many months, and the time to success is often measured in years, as relapses in progress are expected. These goals may sound similar, yet evaluating whether these goals are being met is different for each agency: Police look for absolute, definitive signs of success (e.g., thefts from auto in the target area have decreased by half), while correctional authorities look for comparative, subtle signs of success (e.g., the offender reports less anger since drug use has decreased).

These differences in what police and probation/parole authorities are trying to achieve may make partnerships difficult. With this kind of goal conflict there is unfortunately no global solution, yet importantly, the goal of enhancing public safety is shared. Police and community corrections agencies are encouraged to exploit the leadership and resources of local administrative and community networks. By soliciting many partners, conflicting goals are more likely to each be represented in the collaboration. Though no specific solution to this conflict exists, we can provide seven useful points to consider based on successful interventions:

- The more specific problem solvers are in defining their problem, and the more information that is known about the problem, the more likely it is that a leverage point can be located and exploited for a solution. A failure to create clearly-outlined goals will make it more difficult to resolve the goal conflict.

- The goals of a problem-solving effort should be expanded to include short-term and long-term solutions. When the immediate goal of resolving a crime problem is met and maintained, efforts can shift toward improving offender monitoring and treatment over time.

- Partners should set clear and measurable goals for offender monitoring that are directly tied to community safety (e.g., increase the median time between relapse). This commitment can be built into solutions that will reduce chances for offenders to recidivate.

- Problem solvers should isolate a small group of offenders whose behavior they are trying to change. In this way, recidivism is better understood and more easily corrected. Moreover, police will be able to identify the offenders that need to be removed from the community.

- By creating a specific definition of the crime problem and identifying a specific group of offenders to be targeted, police–community partnerships can provide precise assistance to the offender desistance process. This intensive focus will reduce the number of relapses, increase the time between relapses, and decrease the seriousness of relapses.

- Problem solvers should identify the factors that contribute to offender failure, locating the situations that cause recidivism. To improve offender outcomes, probation and parole authorities will likely need police partnerships to help solve specific problems.

- Offenders may be consulted in classifying the crime problem and developing solutions. Incorporating this expertise will help solve that crime problem, and will add to the rehabilitation of that individual by expanding his/her pro-social network and attitudes.