Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Home Problems Trafficked Women 2nd Ed. Page 3

Responses to the Problem of Exploiting Trafficked Women

Analyzing your local trafficking problem will give you a better understanding of the factors that contribute to it. Once you have analyzed your local problem and established a baseline for measuring effectiveness, you can consider possible responses to the problem.

The following strategies provide a foundation for addressing local trafficking problems. These strategies are drawn from a variety of studies and police reports; several may apply in your community. It is critical that you tailor responses to local circumstances and that you can justify each response based upon reliable analysis. In most cases, an effective strategy will involve implementing several different responses, because law enforcement alone is seldom effective in reducing or eliminating the problem. Do not limit yourself to considering what police can do: instead, carefully consider who else in your community shares responsibility for the problem and can help address it. The cooperation of local businesses, community organizations, local service providers, and—where applicable—military bases will be essential.

General Considerations for an Effective Response Strategy

Although estimates vary, it is likely that at least one-third of prostitutes are either internationally or domestically trafficked women.[46] The police response to trafficking in women will therefore likely be closely linked to its response to the sex trade. Many of the responses described in the Problem-Oriented Guide on Street Prostitution may therefore apply. However, from the point of view of human trafficking, some reconsideration of established police responses to prostitution is necessary.

The response to the exploitation of trafficked women depends on attitudes—attitudes held by the public, stereotypes held by the purchasers of sex and users of forced labor, and police attitudes towards prostitutes. As far as the sex trade is concerned, from a human trafficking point of view, prostitution is primarily an exploitative activity perpetrated against prostitutes, both by their handlers and by the purchasers of sex. Prostitutes are therefore victims, not offenders. Although controversial, this view is crucial in responding to the problem of trafficked women, because those who traffic women for sex often use the women’s criminal designation as a means of exploitation and of keeping the women out of sight of the authorities. It may also provide a ready excuse for purchasers, who may believe that their culpability is lessened because the prostitutes are “just” illegal immigrants. In addition some researchers have argued that stereotypes of prostitutes and the failure to take the exploitive nature of prostitution seriously is stronger in the mostly male dominated field of criminal justice.[47] As far as forced labor is concerned, the public, including criminal justice personnel,[48] find it difficult to believe that slave-like working conditions still exist in the twenty-first century, even in America.

Both situations of exploitation make it very difficult to convince trafficked individuals to testify against their traffickers.† Although TVPA was designed to correct this problem, the number of individuals eligible for protection under the act is still very low, for two reasons: first, the definitions of eligibility for TVPA protection are quite restrictive; second, the police—often the first contact with exploited women—are neither trained to identify trafficked women nor to report them to the appropriate authorities according to TVPA requirements. Thus, educating police, prosecutors, and judges is central to solving the problem of exploiting trafficked women.

† A proactive approach to enforcement is necessary because very few cases will be reported to local police. “Physical and psychological control by the traffickers, fear of law enforcement, illegal immigration status, and language barriers are all factors in limiting the possibility of complaints” (National Trafficking Alert System).

In addition to the information provided in this guide, you can also draw on the resources offered by the U.S. Department of Justice,‡ the Department of State, and the Department of Health and Human Services to develop training courses that will introduce police to the ethnic and cultural issues embedded in this problem and to the skills necessary in interviewing and uncovering victims of trafficking.

‡ In conjunction with the U.S. Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Institute for Intergovernmental Research (IIR) has developed a detailed instructional program for trainers who can then return to their departments and train local officers (SPOG 2005; Institute of Intergovernmental Research (2020 ). For further information, visit the IIR website at http://www.iir.com/.

Besides training, there are a number of preparatory responses that should be undertaken before attempting any of the specific responses recommended below. These are clearly necessary, because it is not possible to reduce the exploitation of trafficked women without having the skills, training, and experience to identify the problem. You should consult the earlier section called Asking the Right Questions as you read the following, which describes the steps that should be taken to prepare for the responses that are directed specifically at reducing and preventing the exploitation of trafficked women.

Preparatory Responses for Identifying the Problem

1. Locating trafficked women.[49] Illegal immigrants are not necessarily trafficked, and trafficking victims are not always illegal immigrants. Thus, although brothels are commonly placed in migrant areas, police should not assume that they will always find trafficked women in those areas. In fact, exploiters may keep victims away from areas where their languages are spoken, even while catering to customers who speak those languages. The obvious place to begin looking for evidence of trafficking is with the vice squad, which will certainly have had contact with trafficked women, although unless they have been trained to look for them, they may not know it. Indicators of the presence of trafficked women and venues where they may be found include:

- Buildings with heavy on-premises security, such as barred windows, locked doors, and electronic surveillance

- Buildings in which women both live and work

- Nail salons, bars, and strip clubs that serve as fronts for prostitution

- Parks and recreation areas where nannies, aux-pairs, and other domestic servants congregate

- Brothels that advertise only in foreign language newspapers or that restrict services to members only

- Advertisements for escorts or other sexual services

- Internet websites and chat rooms

- Workers in hotels, restaurants, domestic situations who cannot speak English

- Hospital emergency rooms and health and abortion clinics

- Ethnic healthcare providers

- Immigrant support groups

- HIV/AIDS community groups

- Locations with large numbers of transient males, such as military bases, sports venues, conventions, and tourist attractions

If there are no visible signs of the sex trade in your area, you should investigate the informal network that exists in all localities. Word of mouth, whether from a bartender or a taxi driver, is a typical way of finding out about the underground sex trade. Other avenues to consider include the internet and social media. Remember, the purveyors of sex must advertise their services; if customers can learn about these services, so can you.

2. Identifying trafficked women. Interviewing women to determine their immigration status requires training and skill. It is particularly difficult to overcome the deep-seated fear and distrust that many such women have of police and other government officials. And in fact, until the passage of TVPA this fear was well grounded, because women who were identified as trafficked were arrested and deported. Furthermore, many trafficked women are trained in what to say to police by their exploiters.[50] They may also be fearful of reprisals by their exploiters for speaking to police, or anyone outside their organization for that matter. The following are indications of possible trafficking.[51]

- Workers who are frightened to speak, especially to police or other officials, including healthcare and social workers

- The presence of very young prostitutes in brothels and massage parlors

- Workers who look sickly or who display signs of physical abuse

- Prostitutes who cannot speak English

- Women who are unable or unwilling to explain how they came into the United States or what they did before gaining entry

- Women who are closely supervised when taken to a doctor or hospital

- Women who are denied clothing other than those provided by a brothel

- Prostitutes whose legal representation is supplied by their trafficker, often as a means of controlling their testimony

- Women who appear fearful of collaboration between traffickers and police

- Women who do not know how their travel documents were obtained or where they are

- Women who paid a fee to obtain travel documents or make travel arrangements

- Domestic workers who appear frightened or apprehensive

3. Protecting trafficked women. How you deal with specific incidents of trafficking is important, not only to the welfare of the victim, but also to establishing relationships with other trafficked women and community groups that may be able to assist in solving the problem of trafficked women. Once you have identified trafficked women, you must protect them from their traffickers and inform them of their rights under TVPA. In cases of severe victimization, you should prevent the woman from returning to her home or workplace, because the risk is very high that the victim will be quickly trafficked to another location and will remain in constant threat of physical abuse. You can help the victim by doing the following:

- Call the national hotline and report the case.

- Obtain information from Federal and State task forces such as the Trafficking in Persons and Worker Exploitation Task Force.

- Contact a local community group that specializes in protecting victims from abuse, such as a women’s shelter or a group that has a tradition of caring for immigrants.

- To help locate these groups call The Office for Victims of Crime (OVC) (1-800-851-3420). The OVC provides a comprehensive list of victim services throughout the United States and the world. These groups can support trafficked victims until they attain certification under TVPA.

- Arrange for medical assistance where necessary.

- Obtain brochures and cards that inform the victim of her rights under TVPA. Many of these are available in several languages on the web, via the hotline, or from the National Trafficking Alert System (NTAS).

- Contact the FBI or the Civil Division of the Justice Department and make sure that you speak to someone who is familiar with the rights afforded to victims under TVPA.

- Ensure that members of your department are informed of the specific criteria for establishing whether a victim qualifies for continued presence, a T-Visa, or other protections under TVPA. There are ample materials and information available from many governmental and private organizations. For a good example of a clear and concise brochure that covers all the basic facts concerning trafficked persons, including how to establish immigrant status and how to determine eligibility for benefits, see Trafficking In Persons, published by the Texas Office of Immigration and Refugee Affairs (available at www.dhs.state.tx.us/programs/refugee). Many states have developed similar brochures and information services.

4. Working with service organizations. As noted, the chances of a trafficked woman revealing her status to a police officer are limited. She may, however, reach out to other groups or agencies. You should therefore:

- Work closely with and support community groups that provide refuge for battered women or that have an interest in taking care of immigrants.

- Develop partnerships with local social service agencies, hospital emergency rooms, ethnic healthcare providers, and others who may provide services to sick or injured trafficked women.

These can be important sources of information on identifying trafficked women and for supporting and assisting trafficked women once they are identified. Do not assume that these organizations are aware of the plight of trafficked women. The idea that something like slavery still exists in the United States is difficult for most people to believe.

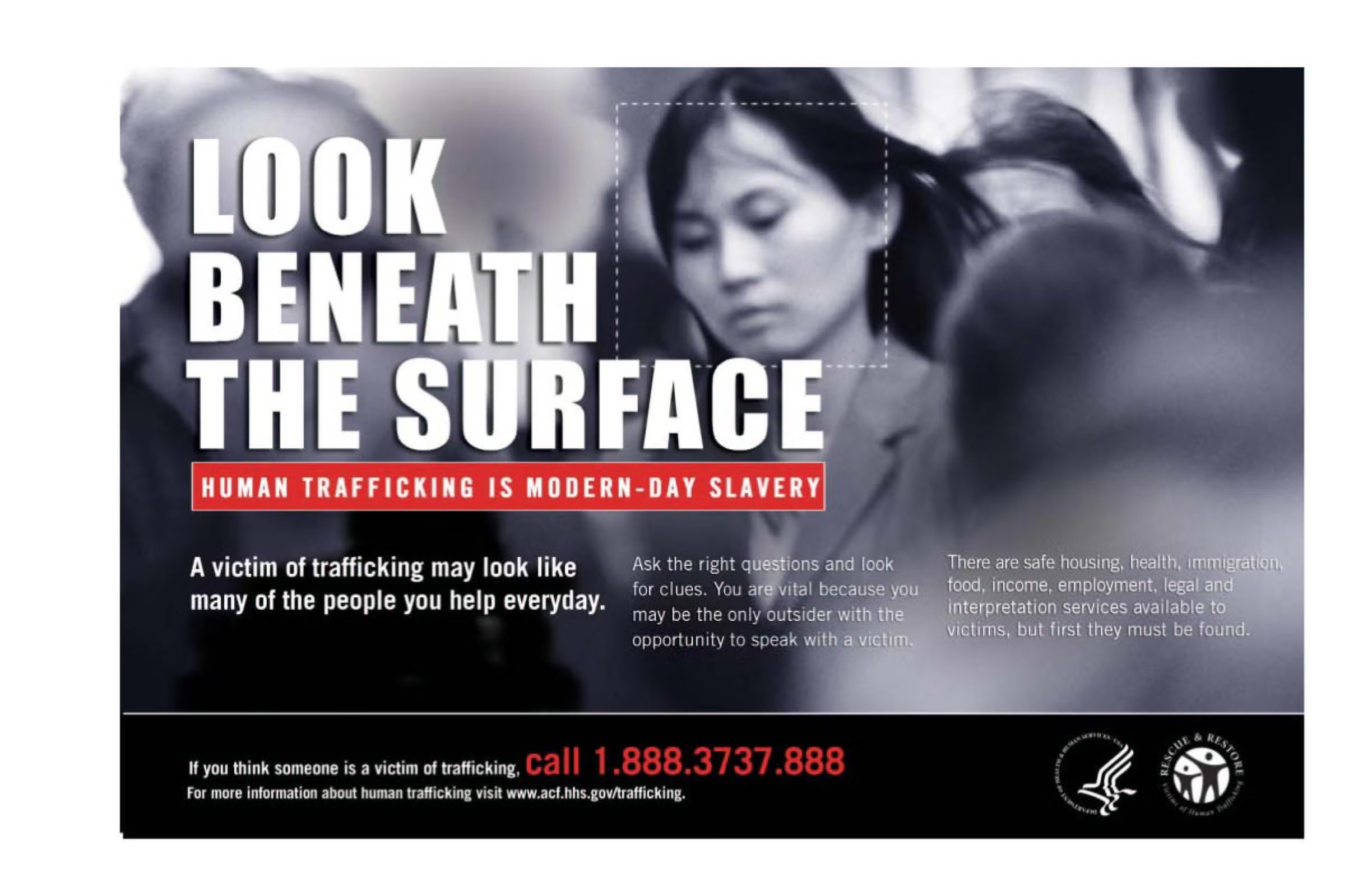

5. Educating the public about human trafficking. Public education through outreach programs and publicizing particular cases that have been successfully prosecuted through the media can raise awareness of human trafficking problems. Efforts to enforce laws against the exploitation of trafficked women, especially prostitution, will be severely limited without public support. Many of the responses below require money, resources, and changes in the local community environment. It will be difficult or impossible to accomplish these goals without community support.† There are many websites that provide posters, brochures, and other materials that can be useful in educating the public about human trafficking; many of these are available in multiple languages. However, probably the most effective means of publicity is informing the media when cases of human trafficking are discovered in your community or elsewhere. There are many such cases available on the web, such as those reported by the National Human Trafficking Hotline.[52]

† The learning module on Street Prostitution (available on the POP Center website at https://popcenter.asu.edu/learning/prostitution/login) provides an excellent opportunity to learn how to respond to the problem of prostitution and emphasizes especially the role of community support in accomplishing the goals of problem-oriented policing.

Specific Responses to the Exploitation of Trafficked Women

There are three approaches to reducing or preventing the exploitation of trafficked women:

- Enforcing laws directed against exploiters, traffickers, and men who purchase sex

- Reducing demand for commercial sex and cheap labor

- Changing the environment so that it is inhospitable to traffickers and exploiters

Enforcing Laws Against Traffickers and Men Who Purchase Sex

6. Adopting an unambiguous enforcement policy. Enforcement attitudes to the sex trade are currently in flux. At the international level, some countries such as Sweden argue that trafficked prostitutes are victims rather than offender and that the purchasers of sex should be punished, not the sex workers themselves. This view was first translated into law in Sweden in 1998 and has increasingly become policy of the U.S. Departments of State and Defense. It is too early to tell whether this approach will be translated into policy or law at the local levels of criminal justice, or whether it will contribute to the reduction of trafficking in women for the sex trade, as claimed by some early Swedish research (see Response 8).[53] Whatever policy your department adopts, it should be clear and unambiguous, leaving no room for ambivalent enforcement, such as occasional sweeps and raids (see Response # 17). The success of any policy also depends upon training officers to understand the diverse ethnic and cultural issues outlined in the preparatory responses above, and the clarity with which the policy of enforcement is applied in that setting.

7. Working with immigration and Labor Department officials. Developing a close working relationship with immigration officials is essential to the successful investigation and prosecution of human trafficking cases because the victim is always the key witness. It will also help in identifying trafficked women and in establishing their immigrant or refugee status. Unfortunately, there is a long history of conflict between local police and federal immigration officials in many parts of the United States. Even though local police have the legal and constitutional responsibility to enforce federal immigration law, they may lack the local authority to intervene or be concerned that enforcing immigration laws will damage their acceptance in local immigrant communities.[54] As noted, some states and sanctuary cities have even passed laws forbidding police from enforcing immigration laws. Because the situation of trafficked women is complicated by their ambiguous status as both illegal aliens and crime victims, extensive policies and procedures must be worked out between local and federal officials, especially in terms of establishing the status of one who has suffered a “severe form of human trafficking” as defined by the TVPA. Without cooperation on both sides, a trafficking victim could be deported or detained for immigration related crimes, thus losing the valuable eyewitness testimony needed to prosecute traffickers. Indeed, in fiscal year 2018, only 526 individuals were convicted of trafficking offenses under the TVPA by the U.S. Department of Justice.[55]

When potential traffickers are encountered, their immigration status can often be verified if they have been issued an Alien Number (also known as an “A number”). ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) maintains a 24/7 hotline (866-347-2423) for U.S. law enforcement officers (called the Law Enforcement Service Center) that can be called to see if a trafficker is already in the ICE system. If a trafficker is not legal, he or she can often be held on immigration charges (smuggling, transporting, or harboring illegal aliens) while a human trafficking investigation continues.

Labor Department (DOL) officials can also be crucial allies in combating the exploitation of women through forced labor. Federal officials from the Wage and Hour Division of DOL can walk onto a worksite and immediately demand to see the I-9 forms of all immigrant workers employed there (law enforcement officials might otherwise need a subpoena to see these same documents). The DOL Wage and Hour Division can also ensure that immigrant workers are paid what they are owed under the law and can help verify subsequent victim claims for legal compensation from their traffickers for lost wages and benefits.

8. Using the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act of 1996 (RICO). Because their labor costs are minimal and they do not comply with standard health and safety regulations, the owners of brothels and sweatshops who use trafficked labor have an unfair competitive advantage over their rivals. Thus, they are ripe for civil suits aimed at their bottom line. RICO can be especially effective in that regard, as it allows for treble damages. Originally enacted by the U.S. Congress to facilitate the prosecution of organized crime, a number of significant RICO cases have found against sweatshops that benefit economically from employing illegal immigrants or trafficked labor.[56] This approach has been used successfully in prostitution cases as well.† Additionally, as recommended in Problem Specific Guide No. 2, Street Prostitution, strict enforcement of zoning laws, nuisance abatement ordinances, and business licensing regulations against properties that allow prostitution can serve to make your community inhospitable to exploiters and traffickers. (See also Responses 13-16.)

† In 2001, police and state and federal prosecutors combined their efforts to prosecute a network of competing pimps. The men were convicted of extortion and involuntary servitude as well as forming a RICO conspiracy (de Baca and Tisi 2002). Joaquin Mendez-Hernandes, also known as “El Flaco,” enticed women to come to the United States from Mexico and Nicaragua with false promises of a comfortable life and easy fortune to be made. Once Mendez-Hernandes lured the women into the U.S., he forced them to perform as many as 20-50 commercial sex acts a day. He threatened anyone who resisted with violence. He also had men in Mexico threaten the children and families of the victims. In 2014, Mendez-Hernandes was sentenced to life in prison for his role in a sex trafficking organization that exploited dozens of women.

Reducing Demand

9. Punishing the purchasers of sexual services and not the sex trade workers. As noted above, in 1998, Sweden passed a law prohibiting the purchase of sexual services. Although the punishment of commercial sex traffickers continued, the law made it clear that rather than being the sellers of sex, prostitutes were in fact the product that was being sold. Swedish authorities claim that as a result of the law the majority of sex purchasers have disappeared and that the number of women trafficked to Sweden has not increased, as it has in other Western European nations.[57] Sweden found, however, that although the law had widespread public support, judges and prosecutors were slow to adopt the view that they should prosecute the buyers rather than the prostitutes. The Swedish police also opposed the law when it was originally enacted.†

† The enforcement of this law has proven very difficult, not only because of attitudes of law enforcement about prostitution, but also because of serious difficulty in interpreting the language of the law, which in many circumstances seems to leave open the possibility of prosecuting prostitutes. In some cases, prostitutes have threatened to expose their clients unless they were paid more money. Others have questioned the Swedish government’s claim that prostitution by trafficked women has not increased at the same rate as other more liberal European countries (Kulick 2003). It is reasonable to conclude that there are no studies of sufficient scientific quality to support either side of the argument.

Although U.S. laws that specify punishments for men who solicit prostitutes vary enormously, they usually impose fines, probation, community service, and publicity; in almost every case they constitute misdemeanors. Publishing the names of buyers of sex has been found to be effective—although there are some difficult legal issues involved[58] and community service has been found to be more effective than fines or jail time (see the Problem-Oriented Guide on Street Prostitution). Some U.S. cities, such as Los Angeles, California and West Palm Beach, Florida have introduced car confiscation programs for men who solicit prostitutes. Other programs combine these punishments with attempts to educate offenders about the social consequences of their acts (see Response #10). The extent to which these programs have been effective in reducing the prostitution of trafficked women in the United States continues to be studied; however, research conducted thus far indicates that they are effective. [59] For example, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has taken substantial action over the past decade designed to reduce or eliminate prostitution and sex trafficking due to the actions of military personnel. Their approach is multifaceted and features a focus on combating demand for commercial sex. While the scale of the military and the level of control over personnel are atypical of most institutions, the objectives and basic steps they have taken can prove instructive to other large organizations and agencies.[60]

10. Changing the attitudes of prostitution customers. A number of cities have introduced “john schools,” in which men convicted of purchasing sex are educated about the damaging consequences that their behavior has on the lives of prostitutes. Various programs of this kind operate in cities such as Portland, Oregon and St. Paul, Minnesota. These may be applied to first time offenders only, as is the case in San Francisco, California, or to all offenders. In general, studies in the United States and Canada have found these programs to be very effective in reducing recidivism.† When enforcement is focused on the buyers, the cost of providing sexual services is increased, because johns, fearful of getting caught, demand higher levels of security, such as private escorts to the place of business.[61] However, commercial sex clients in ethnic or immigrant communities may display differences in their approach to purchasing sex. The cultural orientation of those from regions of the world where prostitution is either legal, tolerated, or encouraged may influence both their behavior and their response to arrest.

† “Of the 1512 men completing the First Offender Prostitution Program in San Francisco (from 3/95 to3/98), only 14 men had been re-arrested for soliciting a prostitute anywhere in California” (Hughes 2004a: 40). A 2016 report by the U.S. Department of Justice indicates that the San Francisco program continued to be highly effective more than a decade later (U.S. Department of Justice 2016).

11. Notifying those with influence over client conduct. Employers, schools, the military, convention organizers, and other individuals and groups can often exert significant informal influence over the conduct of the clients of prostitution. This influence can be leveraged by seeking third-party cooperation to discipline clients who come to police attention. This strategy is not intended merely to shame clients; rather, it is intended to change their behavior through disciplinary systems outside the formal justice system. Keep in mind, however, that some forms of discipline, such as termination of employment, can be severe.

Making the Local Environment Inhospitable to Exploitation of Trafficked Women

While focusing on the demand side of sexual exploitation shows considerable promise, it cannot on its own eradicate prostitution from your locality. This is because the alleged demand by men for sex is not really that strong. For example, in the United States, where about 16 percent of men report having paid for a sex act, only 0.6 percent admit to doing so on a regular basis.[62] In other countries, particularly Latin and Asian countries, the percentage of men who admit to paying for sex is as high as 70 percent. It follows that the demand by men for sex is related to the opportunities and cultural norms that prevail in their respective environments. Therefore, reducing opportunities to buy sex by removing the sex trade from your area stands a very good chance of drastically reducing both prostitution and the exploitation of women.

It can be argued that such a response will merely displace the activity. Although there has been little research on displacement of prostitution, research on the displacement of other crimes suggests that sometimes displacement occurs and sometimes it does not, depending on the particular crime and environment.[63] It has also been found that other crimes may decrease as a result of successful efforts to thwart a specific crime (“diffusion of benefits”) (See the Problem-Oriented Guide on Analyzing Crime Displacement and Diffusion). The following responses are adapted from the Problem-Oriented Guide on Street Prostitution. We strongly recommend that you consult that Guide for further information.

12. Enforcing zoning laws, nuisance abatement ordinances, and business licensing regulations against the owners of properties used for prostitution or forced labor. Prostitution markets depend on other businesses to support them. The police and other enforcement agencies can exert pressure on those businesses by enforcing civil laws and business regulations. Zoning regulations that restrict the sorts of businesses that support prostitution, such as adult entertainment, can be effective. Zoning restrictions have been key in the redevelopment of Times Square in New York City, where prostitution has significantly declined.[64] The police and private parties can file nuisance abatement actions against businesses that support prostitution or forced labor. You should get advice and support from legal counsel before pursuing these options.†

† The Nassau County Police Department (New York) eliminated illegal massage parlors by targeting property owners, in partnership with the local county clerk, fire marshal, and building department (Goldstein submission: http://www.popcenter.org/library/goldstein/1995/95-52.PDF). In 1999, similar results were achieved by the Chattanooga Police Department (Tennessee), which served eviction notices and initiated building condemnations (Goldstein submission: http://www.popcenter.org/library/goldstein/1999/99-07.PDF).

13. Warning and educating property owners about the use of their premises for prostitution or forced labor. Many property owners unwittingly support street prostitution because they fail to appreciate how their business practices allow it to flourish.† You can remind them of their legal obligations and provide business owners and their employees with specific training to help them prevent their properties from being used for prostitution. It is also possible that owners of property that house sweatshops may not realize that the workers are trafficked. You should make sure that they know the warning signs of trafficking. Developing training programs by partnering with businesses in entertainment districts should also assist in identifying trafficked women whether into forced labor or the sex trade.

† In 1998, the Phoenix Police Department's South Mountain Police Precinct (Arizona) identified nuisance rental properties owned by absentee landlords as contributing to prostitution and drug dealing. To alleviate the problem, landlords were required to attend seminars that detailed the debilitating effects of property neglect and offered training on property management. In combination with considerable community support and the release of successful cases to local media, the program led to a successful neighborhood revitalization (Goldstein submission: http://www.popcenter.org/library/goldstein/1998/98-57.pdf). In 2000, The U.S. Department of Justice created a guide entitled Keeping Illegal Activity Out of Rental Property: A Police Guide for Establishing Landlord Training Programs to help police agencies implement landlord training programs in their communities. The training guide is currently widely used by local police agencies across the country (U.S. Department of Justice, 2000).

14. Establishing a highly visible police presence. A highly visible police presence, typically with extra uniformed officers, can discourage street prostitution and may discourage off-street prostitution as well. An extra police presence is expensive, of course, and is only effective if followed up with more permanent strategies; remember too that a heavy police presence can create the perception that an area is unsafe. Alternative methods for establishing a police presence include opening a police station in the area, such as in a storefront, a mobile office, or a kiosk, or affixing anti-prostitution warnings to police patrol vehicles. Private security forces can also be deployed to supplement a police presence.

15. Redeveloping the local economy. The exploitation of trafficked women flourishes in substandard social and economic environments: street prostitution markets thrive under marginal economic conditions; run-down apartments in impoverished neighborhoods are often all that are available to illegal immigrants, who can afford only the cheapest housing; dilapidated buildings in old industrial areas are commonly used for sweatshops. Thus, it follows that economic redevelopment is often necessary to permanently eliminate prostitution markets and forced labor. The idea is that improved economic conditions will foster the establishment of new businesses that are less hospitable to prostitution markets and sweatshops. Although economic redevelopment usually cannot occur without a substantial investment of governmental and private resources, police can play an important role in bringing the need for redevelopment to the attention of the appropriate authorities.†

† Working with local communities to change high risk areas using civil remedies, as suggested in Responses 13, 14 and 16, can be very complicated and is not always effective (Mazerolle and Roehl 1999). See also the Problem-Solving Tools Guide No. 5 on Partnering with Businesses to Address Public Safety and Response Guide No. 11 on Using Civil Action Against Property to Control Crime Problems.

Responses with Limited Effectiveness

16. Legalizing or otherwise tolerating prostitution. There are two closely related reasons usually advanced for legalizing prostitution. First, decriminalization puts buying and selling sex on the same footing as other commercial enterprises, thereby removing both the moral stigma and the well-known criminal justice issues that surround the policing of the sex trade. Second, when the sex trade is treated like any other business, it becomes subject to all the usual health, safety, and environmental regulations, thus protecting the health and welfare of the prostitutes. The latter was the rationale underlying the legalization of prostitution in New Zealand in 2004. There is evidence, however, that because compliance with health and safety regulations increases the cost of doing business, legal prostitution can create a black-market sex trade populated by trafficked women. Legalization can also lead to an increase in the demand for the sale of sex,[65] because as legitimate businessmen the purveyors of prostitution can use sales and advertising tactics to increase their market shares. A final issue, which is the crux of this policy debate, is the moral argument: that prostitution converts a woman’s body into a commodity, even if she does it willingly.[66] Clearly, this debate involves deep philosophical questions that no single police department can solve on its own, at least not without lengthy consultation with civic and community leaders.

17. Punishing prostitutes. Although in most jurisdictions of the U.S. the prostitute remains criminally liable for her actions, the levels of enforcement or punishment that are applied against prostitutes vary enormously across jurisdictions and communities. The idea that prostitutes are both offenders and victims provides excuses either for inaction or for inconsistent and ineffective enforcement practices, such as sudden sweeps and raids – perhaps the most common police response (see the Problem-Oriented Guide on Street Prostitution). Because of the highly vulnerable situation of a trafficked woman who is a sex worker, punishment will most likely drive her further into the clutches of her traffickers, ensuring that she will never cooperate with the police, making investigation and prosecution of traffickers that much more difficult. It will be necessary, therefore, for your department to have a clear policy on the levels of enforcement to be applied to prostitutes, and for the vice squad, should there be one, to be well trained in detecting the presence of trafficked women in advance of any crackdowns or raids.