Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Home Problems Trafficked Women 2nd Ed. Page 1

Exploitation of Trafficked Women, 2nd Edition

Guide No. 38 (2020)

by Graeme R. Newman and James Corey

The Problem of Exploiting Trafficked Women

This guide begins by describing the problem of exploiting women who have been trafficked into the United States, and the aspects of human trafficking that contribute to it. Throughout the guide, the word “trafficked” shall mean internationally trafficked, unless otherwise stated. Additionally, the guide’s focus is on the final period in the process of trafficking at which women are further exploited by those into whose hands they are passed. This is the point at which human trafficking becomes a problem for local police and so the guide identifies a series of questions that can help analyze local problems related to trafficking. Finally, it reviews responses to the exploitation of trafficked women and examines what is known about the effectiveness of these responses from research and police practice.

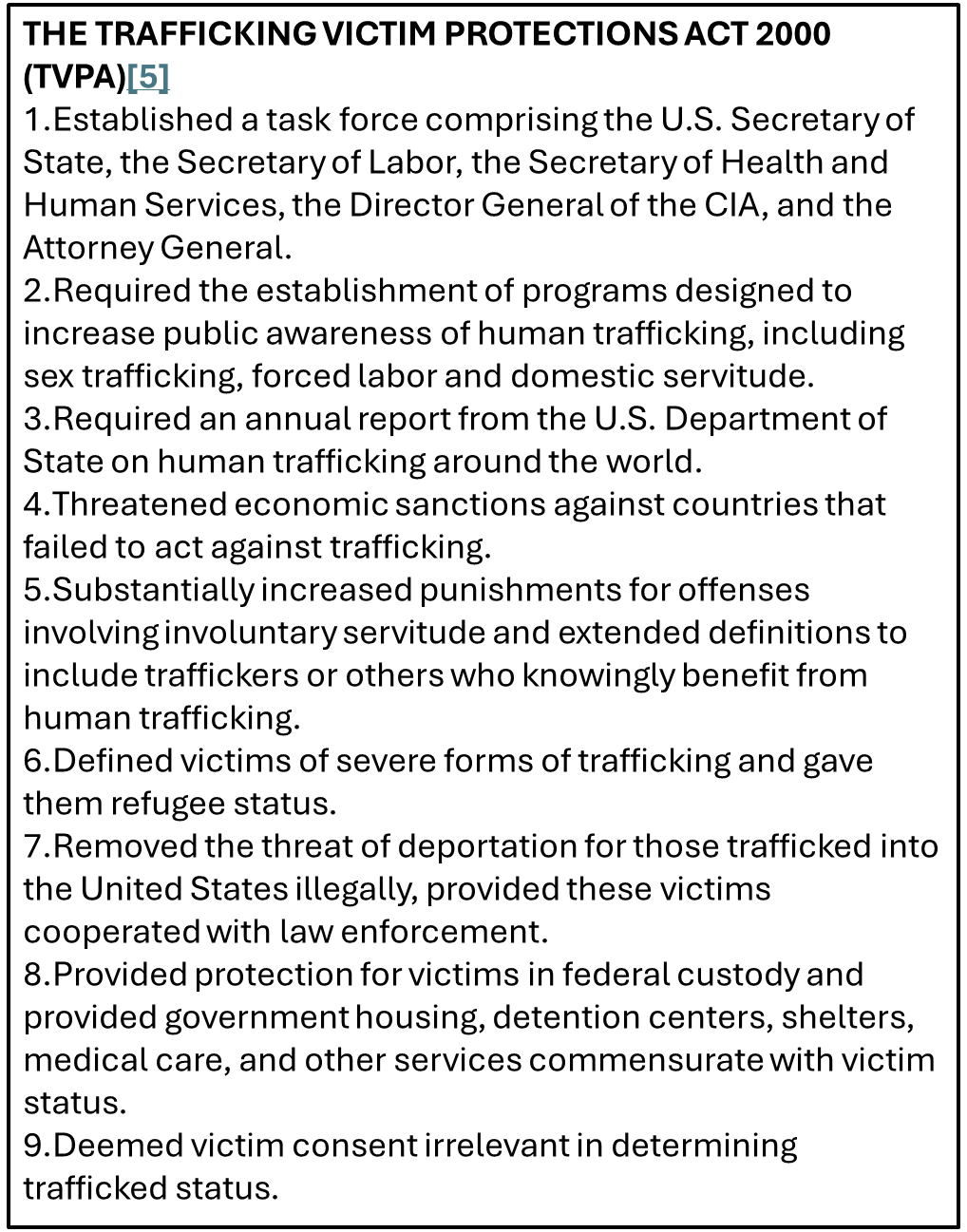

Concern about the exploitation of women who have been trafficked into the United States derives from the international issues of human trafficking and slavery.† The characteristics of international human trafficking, including the profits, resemble those of the international drug trade.[1] In the United States, until the passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000, human trafficking was approached as an immigration problem, which meant that police viewed trafficking as a federal rather than a local responsibility. The protections established by the TVPA have been strengthened and reauthorized every five years starting in 2005. The most recent reauthorization occurred in 2017. The information in this guide reflects the most current information. The TVPA clarified the definition of human trafficking—a particularly difficult problem, as will be seen below—and introduced a number of important protections for trafficked individuals (see BOX 1). The TVPA defines two forms of severe human trafficking:

- “…sex trafficking in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age;”

- …“the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.”[2]

† The trafficking of women within the United States is an old concern, dating back at least to the Mann Act of 1911, which criminalized taking persons across state lines for the purpose of prostitution. This law was directed towards prostitution in particular, without regard to immigration issues.

Because some 70 percent of internationally trafficked women end up in the sex trade, the effect of the TVPA is to define many such women as crime victims rather than criminals. Whether pressed into forced labor or prostitution, the exploitation of these individuals is continued upon entry into the United States, whether in the same hands of those who trafficked them, or whether passed on to others who profit from commercial sex or cheap, often forced, labor.

The TVPA does not require that a trafficked person be actually transported anywhere; it simply requires that the victim’s freedom be constrained by force, fraud or coercion. The focus of this guide, however, is on those women who are transported into the United States for the purposes of commercial sex or forced labor. The operational elements of forced labor, such as occurs in domestic service, agriculture, and sweatshops,[3] are similar to those of forced prostitution: in both cases women may be kept in slave-like conditions, exploited for their labor and are physically and mentally abused. They also share the same trafficked experience: a system built on fraud, coercion, and false promises, which is meant to ensure that the women remain under the control of their traffickers from the moment they are recruited continuing indefinitely through forced labor or the commercial sex trade.[4]

Related Problems

Exploiting internationally trafficked women is only one of a number of problems that are related to or are examples of, human trafficking. Other related problems not directly addressed by this guide include:

- Trafficking in children, sale of babies, and illegal adoptions

- Kidnapping of children

- Child pornography (see Problem-Specific Guide No. 41, Child Pornography on the Internet)

- Sex tourism

- Trading in body parts

- Smuggling of immigrants

- Identity theft (see Problem-Specific Guide No. 25, Identity Theft)

- Street prostitution (see Problem Specific Guide No. 2, Street Prostitution)

- Serial murder of prostitutes

- Illegal employment of aliens

- Domestic trafficking for forced labor

- Juvenile runaways who are drawn into prostitution (see Problem-Specific Guide No. 37, Juvenile Runaways)

- Stalking (see Problem Specific Guide No.22, Stalking)

- Domestic abuse of mail order brides

- Homeless citizens who are trafficked for forced labor (see Problem-Specific Guide No. 56, Homeless Encampments)

- Domestic trafficking of women and juveniles

Extent of the Problem

Statistics concerning human trafficking are necessarily unreliable because of the clandestine nature of the activity and the difficulties in defining it.[6] The U.S. State Department estimates that between 600,000 and 800,000 persons were trafficked across national borders worldwide between April 2003 and March 2004. Eighty percent of these were female, 70 percent of whom were trafficked for sexual exploitation.† In 2019 the U.S. Department of State added to previous reports that between 14,500 and 17,500 are trafficked into the United States each year.[7] Most originate in poorer countries, where human trafficking has become a significant source of income;‡ these include states in Latin America, Africa, Asia, the Commonwealth of Independent States of the former Soviet Union, and Central and Eastern Europe. Most women are trafficked to developed countries, with the United States being the most popular country of destination.[8] Human trafficking is reportedly as highly profitable a business as are arms smuggling and drug trafficking.[9]

† Sixty to seventy-five percent of trafficked women in prostitution have been raped; 70 to 95 percent have been physically assaulted (U.S. State Department 2005; Phillips 2017).

‡ The International Labour Organization (2014) estimated that sex trafficking globally generates $99 billion in illegal profits.

In fiscal year 2003, the number of victims certified or eligible for refugee benefits under TVPA was just 151.[10] When this figure is compared to the estimated 14,500 females who were trafficked into the United States in 2003, it becomes clear that either the estimates are enormously exaggerated or trafficking victims are simply hidden from view. The answer is probably somewhere in the middle. Those who exploit trafficked women work hard at keeping their activities hidden from the authorities by constantly changing the locations and telephone numbers of their businesses and by isolating trafficked women from the public. In addition, because the requirements for meeting the TVPA are quite narrow, the collection of the appropriate information concerning the victim may take considerable time and resources. Thus, an important response for local police is to locate and identify trafficking victims who are hidden† in their communities.

† While sweatshop workers may be hidden from the community, exploited women in the sex trade are not hidden in the same way, since their services are often openly advertised. They are only hidden in the sense that the public turns a blind eye to their existence.

Trafficking causes serious trauma to exploited women and adds to existing public health problems. Trafficked women in the sex trade are so isolated from the community that their clients and handlers physically abuse them with impunity, subjecting them to repeated rape and assault. They also deny them prenatal care or medical care in case of pregnancy, infections or injury, and force them to have abortions. Having no recourse, the women are forced to comply with client demands, the majority of whom, research has shown, refuse to use condoms.† Thus, the spread of HIV and other sexually transmitted disease is more likely.‡ Furthermore, women are induced into heavy alcohol and drug use as a means of ensuring their continued dependency on their traffickers.[11] Needless to say, their illegal status makes it difficult or impossible for trafficked women to receive the social and health benefits that might otherwise be available to them.[12]They are understandably reluctant to seek medical attention for fear of being turned over to immigration authorities.

† Historically, trafficked women have been looked upon as transmitters of HIV and AIDS, rather than as victims of the disease. Measures, including forced HIV testing and medical examinations, have been implemented in order to protect the customers and the larger community—not the trafficked victims themselves (HumanTrafficking.com 2004; Polaris, 2017).

‡ Willis and Levy (2002) reported that in some communities up to 86 percent of sex workers are infected with HIV. The U.S. Department of State (2017) asserts that the data provide compelling evidence of the need to eliminate sex trafficking for the prevention of HIV within a high-risk population.

Because they are out of sight of the authorities (though often in plain view of local communities), sweatshops and other forms of forced labor invariably fail to meet health and safety regulations. Sub-standard housing and working conditions are associated with increased illness and injury in these populations.[13] In addition to being beaten and starved, women may be made to work long hours without breaks or forced to work in hazardous or polluted environments. Even in locations where the presence and employment of undocumented immigrants is known, enforcement of health, safety, and labor regulations is at best sporadic.[14] Language and cultural limits may prevent victims from understanding and appreciating both the risks in the workplace and the use of preventive measures. Injury and death rates of foreign workers have been shown to be higher than normal in some work environments.[15]

The illegal status of trafficked women also makes them ready victims of other crimes. For example, undocumented immigrants are often easy and lucrative robbery targets, because those few who manage to earn any money at all are often fearful of opening bank accounts, lest their illegal status be discovered. And when victimized, many are too fearful to report the incident to the police.[16] Furthermore, traffickers in the sex trade tend to concentrate their activities in immigrant communities that are often neglected by local government, which results in a higher incidence of crime.[17]

The Four Stages of Human Trafficking

Table 1 displays the typical stages of human trafficking and the techniques used at each stage. These techniques are listed as examples and may differ depending on the particular recruiting locality. and the constraints or opportunities that may arise in moving humans across borders. Depending on the organizational sophistication of the traffickers, the third or even the fourth stage of exploitation may be directly linked to the initial stage of recruitment; that is, recruiters who are organizationally linked to the delivery end of the process may select women specifically for particular tasks, such as domestic servitude, escort services, brothels that specialize in providing very young women, or cheap labor for garment industry sweatshops. Although the extent to which all stages of trafficking are linked is unknown, it is usually assumed that where gangs or criminal syndicates are involved, considerable linkage exists.

Table 1: The Four Stages of Human Trafficking

| Stage | Strategies | Techniques | |

ONE Recruitment |

|

| |

TWO Transportation and entry |

|

| |

THREE Delivery and marketing |

|

| |

FOUR Exploitation |

|

|

† Fees to traffickers and recruiters range from $2,000 to $47,000 and often vary by countries of origin: e.g., $40,000 to $47,000 for Chinese women, $35,000 for Korean women, and $2,000 to $3,000 for Mexican women (Raymond and Hughes 2001; U.S. Department of State 2019; UNODC 2018).

‡ In the Philippines, overseas workers are required to send back a percentage of their wage as a condition of permission to travel abroad (Gatmaytan 1997; UNODC 2018). The Dominican Republic depends on more than 100,000 women working abroad as a source of foreign exchange (Wijers and Lap-Chew 1999; UNODC 2018).

Recruitment

Although there are many reported cases of kidnapping for trafficking purposes—as well as reports of parents selling their daughters to traffickers—it is likely that the majority of trafficked women are recruited through fraud, deception, and other enticements that exploit real social and financial needs.[21] A typical human trafficking scheme begins not with violence or coercion but rather as a confidence game—the young woman is convinced by traffickers that a desirable job awaits her in a foreign country. At that point, she believes that she is going to voluntarily participate in a smuggling scheme, in which she will incur a debt in return for being brought into the destination country. In the case of individuals trafficked for forced labor, the victim may enter into a “contract” with the trafficker that is very much against her interests.† The woman may be enticed by the offer of a “loan” for travel to the United States or of aid in finding employment. The complicated interplay between trafficking and smuggling is very much at work here (see BOX). Employment agencies are used as a front for these deceptions, as are agencies for mail order brides. Mail order bride agencies[22], ‡ exploit the blurred line between deception, trickery, and the voluntary attitudes of would-be brides.§ However, human trafficking charges under the TVPA must always involve forced labor or commercial sex of some kind. Abuses of mail order bride situations may or may not include these elements. Nonetheless, it is clear that numerous mail order bride agencies utilize the same kind of deception that traffickers do in luring foreign women to come to the United States.

† In one excellent study of women recruited in the Philippines, all women stated that they had willingly agreed to be transported to the country of destination; some even paid the travel costs up front. All those interviewed, however, subsequently fell into heavy debt and became enslaved in the sex trade (Aronowitz 2003). Traffickers may be family members, recruiters, employers, or strangers who exploit vulnerability and circumstance to coerce victims to engage in commercial sex or deceive them into forced labor (U.S. Department of State, 2019).

‡ The United States is the number one importer of mail order brides and the number one importer of Philippine women. Although the victims understand from the beginning that the marriages are shams, they believe the arrangement will benefit them and provide economic opportunity. The reality, however, is very different from their expectations. Traffickers mislead victims with false information about financial remuneration, accommodations, job opportunities, and divorce procedures. Before the victims realize it, they are trapped in a situation based on lies, exploited, and living in fear in a foreign country (U.S. Department of State, 2019).

§ Traffickers find marriage agencies and mail order bride services attractive because as legal businesses they can recruit women openly; they are also virtually unregulated (Lloyd 1999-2000). Traffickers pay recruiters to find victims to serve as brides. These exploitative practices are extremely profitable. For some crime networks, it can be a multi-million-dollar enterprise where human trafficking is just one part of a larger operation involving other illegal activities, such as migrant smuggling and organ trafficking (U.S. Department of State, 2019).

Transportation

Research suggests that the main means of trafficking into the United States is by air.[23] Most often, women are trafficked according to a previously planned route, often using the services of a tourist agency that may or may not be linked to trafficking. Trafficked women may be transported across borders with or without legitimate documentation. The use of forged or stolen passports and visas and the use of tourist visas is common.† Again, the interplay between smuggling and trafficking (see BOX 2) is evident at this stage of the process. In locations where borders are porous or stretch across inhospitable or isolated territory, smugglers may offer safe passage across established or known routes. In locations where border security is tight, traffickers may help individuals conceal themselves in trucks or trains in order to enter the country illegally. Military bases are also popular points of entry.

† One study found that over 50 percent of trafficked women entered the Unites States with tourist visas and overstayed their visas (Raymond et al. 2001). A 2016 report issued by the Department of Homeland Security investigators found that “from 2005 to 2014 more than half of the known traffickers that they examined used visas to bring in victims who were exploited for either forced labor or prostitution” (New York Times, Jan. 11, 2016).

BOX 2: Trafficking vs. Smuggling

Smuggling and trafficking are closely connected. Generally, smuggling does not involve coercion, but rather is performed at the request of the alien, who pays a fee for safe, albeit illegal, passage. In its simplest form, it involves only the second stage of trafficking: transportation. However, trafficked women who begin their trip voluntarily may become victims at the delivery stage, when their illegal status is exploited by those seeking cheap labor. If the smuggling is part of an organized activity, the smuggler may deliver the smuggled individual directly into the sex trade or another form of forced labor. In this case, the individual is both smuggled and trafficked.[24]

Trafficking

| Smuggling

|

Delivery/Marketing

Both before and after a woman has reached the United States, her services can be marketed through standard outlets, such as advertising in personal columns; but by far the most effective marketing is via Internet chat rooms, bulletin boards, and the many websites that offer matchmaking services for men and women.[25] Where a prior arrangement has been reached, the trafficked woman is handed over to her intended employer once she reaches her destination. Forced prostitution may also be confined within particular ethnic communities, where men seek to purchase sex from women or young girls of their own ethnicity. This serves to further isolate trafficked women from the broader community.[26] Research suggests that there is considerable trafficking of women between various U.S. cities. Frequent movement of women serves three purposes: first, it makes detection more difficult and removes the incentive for local investigative agencies to become involved; second, it provides a variety of women for customers; and third, it inhibits women from establishing ties to their communities.[27] In cases where there is no delivery to a specific person or organization, the woman is technically not trafficked, but smuggled. In this case, if she is young, without family, and without the ability to speak English, she may end up in the sex trade, and her trafficked status will be difficult to determine by local police.

Exploitation

Trafficked women are extremely vulnerable, for three reasons. First, as illegal aliens, many women who do not know they have rights are fearful of seeking assistance from police or other service agencies. Second, women and their families are often in debt to the traffickers who exploit their labor. Third, should a woman’s situation, such as working in the sex trade become known back home, her family’s honor may be damaged. As a result, those who “employ” trafficked women have enormous control over them. In effect, conditions of employment become conditions of slavery.† However, the definition of exploitation is difficult, because trafficked persons—and even legal immigrants—often consent to exploitation in the hope that they can improve their circumstances by doing so.[28] This creates a serious problem for local police, because victims may refuse to cooperate and may even resist attempts to improve their circumstances.

† In the pre-Civil War South, replacing a slave cost the modern equivalent of $40,000. Slaves in the twenty-first century can be purchased for as little as $90 (Bales, 2012). For example, a family in Thailand was reported to have sold a daughter into the sex trade in order to buy a television set (Florida State University, Center for the Advancement of Human Rights, 2003:14).

In fact, the problem of definitions of the many activities involved in the trafficking of women is considerable. Only in recent years has a definition of human trafficking been agreed upon internationally. It was not until the passage of TVPA in 2000 that the U.S. Congress defined trafficking and its associated terms in an attempt to clarify the difficult overlap between smuggling, trafficking, coercion, consent, bondage, and exploitation. The extremely complex interplay among these terms as well as their links to other crimes is displayed in Appendix B. The definitions now accepted are reproduced in the accompanying Box 3.

Factors Contributing to the Problem of Exploiting Trafficked Women

Understanding the factors that contribute to local trafficking problems can help frame local analysis, identify effective remedial measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

The Market for Commercial Sex

Supply. The international proliferation of trafficking has created a supply of trafficked women that is so large that it drives the market. Countries that make no attempt to control human trafficking† use the trade as a means of importing foreign currency, especially U.S. dollars and Euros. This is achieved both by encouraging sex tourism in the originating country and by tacitly approving the exportation of women to wealthy countries.[31] Globalization has facilitated the movement of cheap labor from one country to another. Thus, even those women who are not trafficked into the sex trade add to the plentiful supply of undocumented migrant labor at best, sweatshop and forced labor at worst.

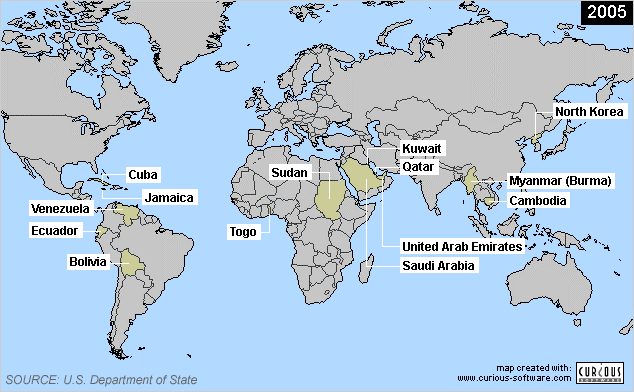

† The TVPA established a set of standards for countries to combat trafficking. Countries are rated annually according to these standards and allocated to one of three tiers: (1) full compliance; (2) some compliance; and (3) no compliance or no effort to comply. As of 2017, all countries are required by U.S. law to collect and publish prosecution and conviction statistics on human trafficking. Countries making no effort to combat trafficking are subject to various U.S. sanctions (U.S. Department of State 2004, 2005, 2017).

Demand. The demand issues surrounding trafficking for forced labor are simple enough: because illegal or quasi-legal businesses can gain considerable advantage by employing cheap labor, there will always be demand for such labor. The demand issues involved in trafficking for the sex trade are much more complicated and subject to considerable debate. Some argue that human trafficking for the sex trade is simply a response to a natural need; that is, men will be men. Others argue that this is a misconception, that rather than men’s sexual needs being such that prostitution must exist to fulfill them, the truth is that men’s sexual appetites respond to the opportunities offered them by the purveyors of prostitution.† (See also Response #9 for an elaboration of this point). In other words, it is the market— the trafficking in women—that creates the demand, not the customers. If there is a plentiful supply of vulnerable women and girls, a profitable business plan follows: offer the services of young women that cater to any customer preference at a competitive price and pay the women little or nothing.‡

† This is the rationale that underlies the Swedish legislation outlawing the purchase of sexual services. As its advocate says: “It is the market that is the driving force. Demand is defined by the services produced, not vice versa, which contradicts certain popular traditional market theories” (Sven-Axel Mansson, interviewed by Maria Jacobson 2002). This assertion is supported by a 2012 report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. “The illicit markets of prostitution and sex trafficking are, like any other markets, driven by demand. Wherever demand occurs, supply and distribution emerge” (Shively et al. 2012).

‡ There is some evidence of a growing demand by purchasers of sex for foreign women of various ethnic backgrounds. There is considerable evidence that men’s sexual expectations are driven by ethnic stereotypes and myths (Hughes 2004; Shively et al. 2012).

Customer and Trafficker Attitudes

The sex trade. The customers of the sex trade reveal callous attitudes towards the trafficked women they rent.† In the case of prostitution—whether the prostitute is trafficked or not—men adopt the view that they “own” the prostitute for the period for which they have paid and believe that they have a right to do whatever they please, including physical and psychological abuse.[32] The purveyors of prostitution, whether pimp or madam, do not demand compensation if the customer damages the woman. Indeed, they routinely abuse prostitutes themselves.[33] Here again, profit is the key. Trafficked women in the sex trade quickly depreciate in value—particularly, where beauty and youthfulness are important to the customer. Youth and beauty are cheap to replace where there is a plentiful supply of trafficked women.

† Sex trade customers commonly report that it is none of their concern if prostitutes are trafficked or even imprisoned in the brothel. While some feel sorry for the prostitute’s situation and may even offer help, they nevertheless continue to purchase her services and expect the same services from trafficked as from non-trafficked prostitutes (Seabrook 2001; Shively et al. 2012).

Domestic servitude. Employers of domestic servants who are trafficked women display attitudes not so much indifferent as paternalistic. Interviews show that employers often treat the trafficked women in their service as children without rights, sometimes subjecting them to physical and mental abuse, and placing considerable restrictions on their movements, including low pay and little or no time off. In many cases, employers feel that they are doing the trafficked woman a favor by providing employment that would otherwise be unavailable to an illegal alien.[34] In short, because the conditions of employment within households are invisible to the authorities, working conditions that would be important outside the household are seen as irrelevant.[35]

Forced labor. Debt bondage is the most frequent type of coercion employed against women in labor trafficking situations. Rape and sexual assault are also frequently used by traffickers to “maintain” women in labor trafficking situations. Whatever the technique used to maintain debt bondage, —whether on a rural farm or in an urban sweatshop—the obvious advantage to employing trafficked women is that they are cheap, thus increasing profit and competitive pricing. Money is saved in many ways. Because these businesses are operated on premises that are hidden from public view, they can dispense with health and safety compliance. Of course, wages—if any—never match the minimum wage.† And in fact, wages are garnished to pay the “loans” that financed the trafficked individual’s transportation to the country of destination.[36]

† “Every floor is a rabbit warren of corridors and numbered doorways, a labyrinth of iron grilles and black wire mesh reminiscent of a reform school, or a prison. Behind every one of these forbidding doors is a garment shop, where mostly undocumented immigrant workers toil away with scissors, sewing machines and industrial irons for poverty-level wages for up to 12 hours a day.” Description of a sweat shop in the south end of downtown Los Angeles (Gumbel 2001).

Divided Public Attitudes

Prostitution. Sex trafficking of women involves commercial sex where the victim’s ability to legally consent to the sex act is negated through some form of force, fraud or coercion that is employed against her. There are widely differing views of prostitution and in general who is responsible for it.[37] These often-conflicting opinions affect community responses and the extent of police intervention. Public ambivalence is reflected in the incredible patchwork of state and local prostitution laws and ordinances, some punishing the purchase of sexual services, some punishing its sale, some targeting pimps and brothel owners, and still others criminalizing all of the above. The result is inconsistent enforcement by local police, who carry out well-publicized crackdowns from time to time. There is growing evidence that women who are trafficked into prostitution do not differ greatly from domestic prostitutes who have not been trafficked: neither group has chosen the profession voluntarily. Many report that they do not want to work as prostitutes, would leave the profession if they could, and that they were recruited into prostitution as girls or teenagers.[38], † Of course, those women who entered into the sex trade as minors, could not have done so voluntarily from a legal standpoint.

† The focus on the victimization of trafficked women has put the spotlight on all prostitutes, making it clear that the trafficked prostitutes are victims, not offenders. Thus, many now advocate that enforcement attention should be shifted to the purchasers of sex. The recent announcement by the U.S. Department of Defense that military personnel purchasing sex will face court martial is the first significant indication of this shift (Jelinek 2004).

Immigration. There are widely differing public views of immigrants, both legal and illegal.[39] A significant portion of the U.S. population believes that national borders should be open and allow movement of people between jurisdictions with few or no restrictions. Indeed, sanctuary states and cities (e.g., Oregon and San Francisco) have policies and even laws that prohibit state and local police agencies from using money or equipment to apprehend suspected violators of federal immigration law.[40] Further, many states and cities that are not designated sanctuaries do not report illegal immigrants to the authorities simply because immigration is seen as a matter for federal rather than local law enforcement. On the other end of the political spectrum are those who firmly support controlled borders, which allow movement of people between different jurisdictions, but places significant restrictions on this movement. Controlled borders always have methods for documenting and recording [people] movements across the border for later tracking and compliance checks with border crossing conditions. Local and federal law enforcement assume proactive roles in maintaining and strengthening control measures both at the border and within the nation’s boundaries. Both ideologies, though vastly different, result in either the ease or the necessity for traffickers to keep their victims isolated and out of sight of the authorities.

Organized Crime

Europol[41] classifies trafficking networks into three groups:

(1) Large scale mafia-like networks such as the Russian and Albanian syndicates that control about 60 percent of prostitution in Western Europe. These networks also traffic in drugs,† but more recently have turned to trafficking in women because the profit margins are higher. Highly organized from the recruitment to the exploitation stages, these groups are well connected financially and politically and are typically cruel and brutal in doing business.

(2) Medium scale networks that specialize in trafficking women from a particular recruitment country to a particular destination country. These networks usually arrange transportation and also own their own brothels in the destination country.

(3) Informal “family” networks of individuals who have come together to reap the financial benefits of the opportunities provided by trafficking. These individuals usually have legitimate jobs in other fields and operate trafficking businesses on the side. Much of the buying, selling, and delivery arrangements take place via the Internet.

† Drug use is common in prostitution, serving as another weapon to keep trafficked women dependent on their pimps or managers and isolated from the outside world (Raymond and Hughes 2001; Shively et al. 2012).

In general, these observations of the organizational aspects of trafficking have been confirmed for the United States.[42] However, the degree to which trafficking is part of well established organized criminal organizations is unknown.[43]

Attractive Locations

Locations that provide cover for the deployment of trafficked women include the following.

- Communities that tolerate red light districts, strip clubs, and late-night bars and clubs. Where domestic prostitutes are plentiful, internationally trafficked women can blend in without drawing much attention.

- Areas around military bases, where there is a constant supply of men willing to purchase sexual services, frequently from foreign women.†

- Old warehouse and manufacturing districts, where sweatshops can flourish out of sight of local communities.

- Well-off suburbs, where residents employ domestic servants who may be trafficked.

- Isolated rural areas, where trafficked women may be employed as seasonal farm laborers or be used to provide sexual services to male seasonal laborers.

- Locations close to poorly patrolled border entry points or in immigrant communities that are neglected by local government.[44]

- Areas with large immigrant or foreign-born populations that may frequent establishments set up in culturally familiar styles.