Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Prescription Drug Fraud and Misuse, 2nd Edition

Guide No. 24 (2012)

by Julie Wartell and Nancy G. La Vigne

The Problem of Prescription Drug Fraud and Misuse

This guide describes the problem of prescription drug fraud and misuse and reviews some of the factors that increase their risks. It then identifies a series of questions to help you analyze your local problem. Finally, it reviews responses to the problem, and what is known about them from evaluative research and police practice.

What This Guide Does and Does Not Cover

For the purposes of this guide, prescription drug fraud, which falls under the broader heading of pharmaceutical diversion, is defined as the illegal acquisition of prescription drugs for personal use or profit. This definition excludes theft, burglary, backdoor pharmacies,† and illegal importation or distribution of prescription drugs. This guide also discusses common forms of prescription drug diversion, as not all cases of diversion are fraudulent. For example, sharing medication and taking medication without permission are not acts categorized as fraudulent yet still warrant police attention. The related issue of prescription misuse and addiction is also covered, as many offenders become addicted and begin more widespread use through illegally obtaining prescription drugs from family and friends.

† "Backdoor pharmacies" are businesses not licensed/authorized to distribute pharmaceutical drugs.

Prescription drug fraud and misuse is but one aspect of the larger set of problems related to the unlawful use of controlled substances. This guide is limited to addressing the particular harms created by prescription fraud and misuse. Related problems not directly addressed in this guide and requiring separate analysis (such as other illegal methods by which offenders obtain prescription drugs), include the following:

Prescription Drug-Related Problems

- Medicaid fraud. Pharmacy workers sometimes commit Medicaid fraud, usually by substituting generic drugs for name brands, short counting pills, filling prescriptions without a refill, and then overbilling Medicaid. They may also bill Medicaid for drugs they never dispensed.1

- Over-the-counter (OTC) drug misuse. Those who purchase OTC drugs to achieve a "high" are typically youth seeking cough and cold medicines, sleep aids, antihistamines, and anti-nausea agents.2 It is not known to what extent the misuse of OTC drugs increases the risk for prescription drug misuse and/or fraud, or illegal controlled substance use (e.g., heroin use).

- Theft from pharmacies, hospitals, and doctors' offices. Pharmacy workers and healthcare providers, both of whom have easy access to prescription drugs, sometimes steal them.

- Burglary and robbery. Offenders obtain prescription drugs by either burglarizing or robbing pharmacies.

Other Drug-Related Problems

Some of the following problems related to prescription fraud and misuse are covered in other guides in this series, all of which are listed at the end of this guide:

- Open-air drug markets

- Drug dealing in apartment complexes

- Marijuana growing operations

- Rave parties

- Clandestine methamphetamine labs

- Mobile drug dealing

- Drug-impaired driving

For the most up-to-date listing of current and future guides, see www.popcenter.org.

General Description of the Problem

Prescription drug fraud and misuse is a significant and growing problem. State and local police agencies are increasingly reporting diverted pharmaceuticals as their greatest drug threat, based on both prevalence of the problem and related issues of misuse-related crime involvement and gang activity.3 According to a 2009 survey, between 28 and 58 percent of police agencies, varying by region, reported street-gang involvement in pharmaceutical drug distribution.4

Nationwide in 2010, 7 million people self-reported illegal use of prescription drugs in the previous month.5 It is a serious form of illegal drug activity, rivaling activity that involves more traditional street drugs. In fact, a recent study found that following marijuana, prescription drugs are the second most misused category of drugs among young people.6

The healthcare costs alone of nonmedical use of prescription opioids—the most commonly misused class of prescription drugs—are estimated to total $72.5 billion annually.7 The local scope of the problem is similarly dire. Prescription drug fraud and misuse is common across the nation, but its intensity varies from place to place. For example, prescription-opioid pain-reliever overdoses are higher in states with greater retail sales volume of these prescription drugs.8 Overdoses range from a low of 5.5 per 100,000 residents in Nebraska to 27 per 100,000 residents in New Mexico.9 South Florida, and particularly Broward County, is viewed as the epicenter of prescription-opioid misuse, attributed in large part to the prevalence of pain-management clinics, a fair share of which dispense prescription medications inappropriately.10 Users obtain prescription drugs unlawfully in numerous ways, including the following:

- Forging prescriptions

- Consulting multiple doctors to obtain prescriptions ("doctor shopping")

- Obtaining prescribed drugs illegally through the Internet

- Acquiring drugs that were legally prescribed to family members or friends

- Altering prescriptions to increase the quantity11

The true scope of prescription fraud and misuse is largely unknown, due to a number of factors. As with any crime, successful offenders get caught less often, and police never detect most of their offenses. Unlike other crimes, however, much prescription fraud goes undetected because it is not a high police priority; very few local agencies systematically track it. Limited awareness and lack of oversight among doctors and pharmacists may contribute to the problem. Limited education during physician training concerning pain, assessment of addiction liability, and how to use tools to reduce addiction liability also likely contribute to the problem.12

Indeed, nonmedical prescription drug use is a complex issue. From a police perspective, some aspects of prescription drug misuse fall more than others in the domain of policing. For example, doctor shopping or prescription drug theft from healthcare providers, family, and friends, represent clear policing issues. Likewise, police have a lead role in addressing the impact of prescription-drug trafficking and misuse on organized-crime and gang activities, related criminal acts, and vehicle crashes.

But other components of the prescription drug fraud and misuse problem require collaboration with public health departments, substance abuse treatment providers, emergency rooms, and other entities whose missions are more squarely aligned with addressing the addictive potential of misused drugs.

Harms Caused by Prescription Drug Fraud and Misuse

Prescription drug misuse can lead to serious consequences: overdoses from prescription pain relievers and emergency room visits due to pharmaceutical misuse have increased steadily in recent years.13 Misuse of these medications can rapidly escalate into abuse or dependence and require costly rehabilitative treatment. The number of people seeking treatment for prescription drug abuse has also increased: the 2010 National Survey of Drug Use and Health shows that since 2002 the number of Americans receiving treatment for prescription opioid abuse has risen from an estimated 306,000 to 754,000. Whether prescription drug use leads to more dangerous behavior and negative consequences than other drugs is not established; however, one study showed that among a cohort of prescription drug users in rural Kentucky, initiating use with certain medications including benzodiazepines, illicit methadone, and oxycodone, was associated with a higher risk of later injecting behavior.14 This study also found that these individuals' partners and their criminal involvement predicted the transition to injecting. This suggests coordination among police, criminal justice, and health officials may help reduce negative outcomes resulting from prescription drug use disorders.

The need for money to purchase prescription drugs for nonmedical use can also contribute to the incidence of burglaries: prescription drugs are chief among items most commonly stolen in residential burglaries, along with cash, jewelry, and guns.15 As you contemplate how to approach the problem and impact of prescription fraud and misuse, you should carefully consider the contexts in which they may play a lead crime-control and prevention role versus a secondary, or referral, role—one of aiding stakeholders in making connections to entities that are best equipped to address the issue.

Factors Contributing to Prescription Drug Fraud and Misuse

Understanding the factors that contribute to prescription fraud and misuse will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

Misuse of and Addiction to Prescription Drugs

Prescription drug misuse is significant and rising rapidly, with some observing that it is the nation's fastest-growing drug problem.16 In 2010, about one in four illicit-drug users reported that their initiation into illegal drug use began with prescription drugs.17 This amounts to 2 million Americans over the age of 12 who illegally used pain relievers for the first time in 2010 alone.18 Although this number is similar to that of people reporting first-time use in 2000, addiction rates are on the rise. For example, substance abuse treatment admissions associated with prescription opiate abuse increased from 8 percent of all opiate admissions in 1999 to 33 percent in 2009.19 Moreover, drug overdoses from prescription opioids in 2008 exceeded those for cocaine and heroin combined.20

Research shows that people who misuse opioids often obtain them through a legitimate prescription to treat pain or a medical condition. In this case misuse may constitute taking more than prescribed. People with mental health conditions such as depression or anxiety are also vulnerable to this type of misuse.21

Types of Prescription Drugs Misused

Overall, the most commonly misused prescription drugs fall within the class of controlled substances termed opioid pain relievers, such as hydrocodone and oxycodone. The prescription drugs that police agencies most frequently report as commonly misused include Vicodin® (hydrocodone), OxyContin® (oxycodone), Lorcet®, Dilaudid®, Percocet®, Soma®, Darvocet®, and morphine. Many of these top the list of prescription drugs used non-medically by youth and young adults, who tend to favor pain relievers such as codeine, methadone, Demerol® (meperidine), Percocet, Vicodin, and OxyContin.22

Many experts attribute the growth in prescription drug misuse in part to the introduction in the mid-1990s of OxyContin, an oral, controlled-release form of oxycodone that acts for 12 hours. Oral OxyContin is a very effective pain reliever. However, when injected or snorted, users experience euphoria with rapid onset. In addition, nonmedical use of prescription stimulants prescribed for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), such as Adderall® and Ritalin®, are increasingly common, particularly among college students.23

Types of Offenders

Unlike perpetrators of other drug-related crimes, prescription drug fraud and misuse offenders span a wide range of ethnic, social, educational, and economic backgrounds. Often, they become addicted to drugs legally prescribed to them and then try to obtain additional drugs illegally. Other offenders, who are already addicted to street drugs, discover how to convert prescription drugs into more potent substances.

Youth and young adults. The most dramatic increases in illegal prescription drug use in recent years have been among youth. Of the estimated 6.2 million Americans using prescription drugs non-medically in 2010, nearly half were age 12 to 25.24 Nonmedical use of prescription psychotherapeutic drugs among 12- to 17-year-olds increased by more than 60 percent between 1999 and 2006.25 Nonmedical prescription drug use is often accompanied by other illicit drug use: about half of teenagers who have misused prescription painkillers reported drug and/or alcohol use,26 and nearly two-thirds of 12- to 25-year-olds who had used prescription drugs non-medically in the past year had also used marijuana in the past year.27 The nonmedical use of prescription drugs is often the first type of drug misuse in which young people become involved: for example, one-third of people age 12 and older reported that their first illicit drug use was of a prescription drug.28

Another trend is the nonmedical use of prescription stimulants such as Adderall, Ritalin and generic amphetamine salts by high school and college students, primarily to gain focus and improve studying.29 Students have also reported combining Xanax® with cola drinks and taking Vicodin before alcohol consumption to speed the onset of intoxication.30

Youth are a particularly vulnerable population for prescription drug misuse, perhaps due to peer pressure and a lack of knowledge of the law. Indeed, roughly half of teenagers reported misusing prescription drugs because they are not illegal.31 Smaller but meaningful shares of teens also reported that there is less shame in being caught using prescription drugs compared with using controlled substances.32

College students also engage in nonmedical prescription drug use, particularly opioid use. Roughly 7 percent of college students reported nonmedical use of prescription opioids,33 and 4 percent reported abuse of prescription stimulants,34 in the past year alone. The nonmedical use of prescription drugs among college students is most commonly facilitated by students sharing their legally prescribed drugs with others.35 Students reporting misuse of prescription drugs also report much higher levels of marijuana and cocaine use, binge drinking, and drunk driving.36

Women.37 Although women and men have roughly the same rates of nonmedical use of psychotherapeutic drugs and pain relievers,38 among women and men who use a sedative, anti-anxiety drug, or hypnotic, women are almost twice as likely to become addicted.39

Older adults. The nonmedical use of prescription drugs among adults age 50 to 59 nearly doubled between 2002 and 2009.40 Older adults may be more susceptible to prescription drug misuse because they are prescribed such drugs at a rate three times that of the general population, and also often have trouble following their doctor's dosage instructions.41 Pain relievers are the most commonly misused prescription medicine among older adults, followed by anti-anxiety and insomnia medications.42

People with existing substance use disorders. Several police agencies have observed increases in prescription drug misuse among heroin addicts and users of other illegal drugs, who take prescription drugs to ease the effects of those other drugs.43 Others combine multiple drugs to produce new and different highs.44 Conversely, some experts have observed that those who become addicted to oxycodone and lose their health insurance often turn to heroin for a similar, cheaper, high.45

Healthcare workers. Healthcare workers are in a unique position to acquire and misuse prescription drugs. Offenders may steal drugs while working, steal prescription pads, or write illegal prescriptions for friends. Of the approximately 250 felony arrests made by the Cincinnati Police Department's Drug Diversion Unit, on average annually, almost 20 percent involved healthcare workers, including doctors, nurses, and hospital workers, who were either diverting the drugs to support their own drug addictions or selling them for profit on the black market.46

Types of Fraud

Prescription drug fraud can take many forms. The most common tactics are to forge or alter a prescription, to doctor shop, and to phone in fraudulent prescriptions posing as a doctor's office employee. Theft of prescription pads is also common.

Forging prescriptions. Forging prescription slips has become easier as the cost of high-quality copying equipment has dropped. Some offenders even go so far as to paint glue on the top edge of the slip to make it appear it was ripped from a pad.

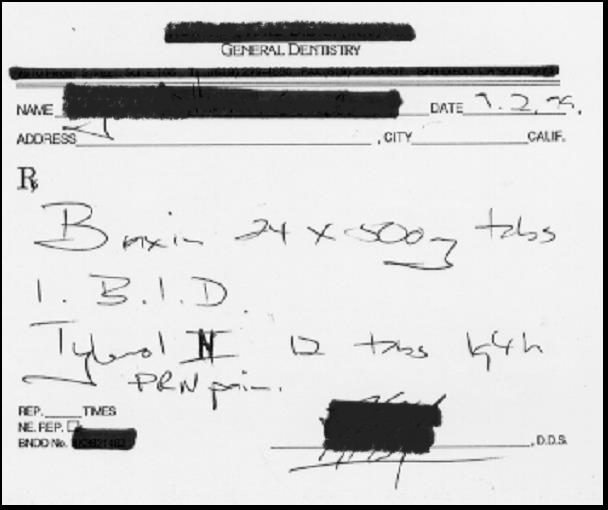

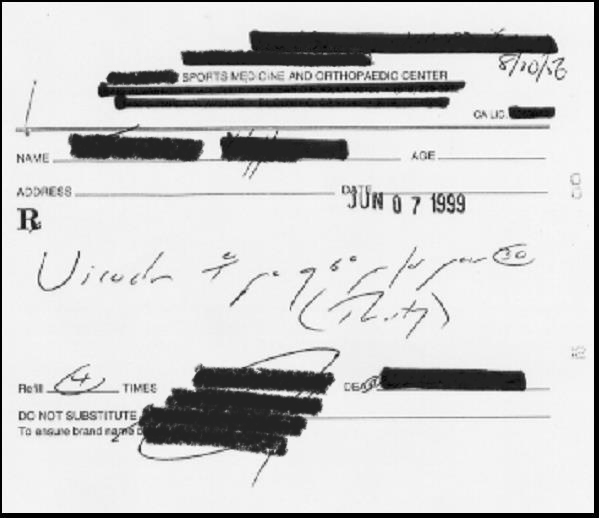

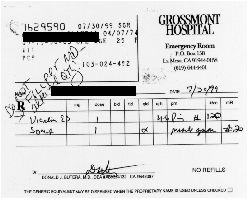

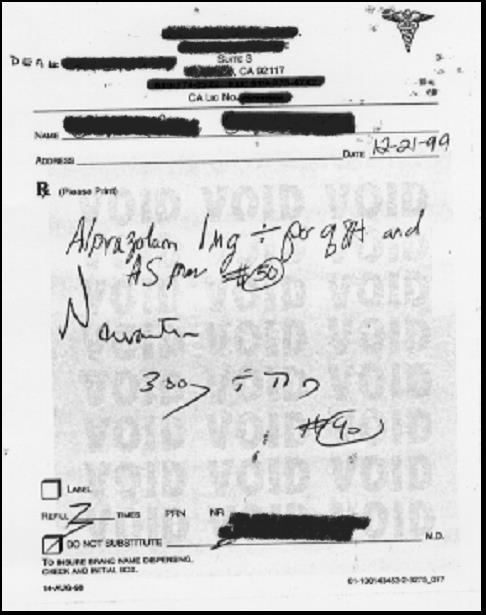

Altering prescriptions. The first resort of many users who are addicted to legally prescribed drugs is to alter a legitimate prescription by changing the type of drug, increasing the number of refills, increasing the quantity, or adding drugs (see Figures 1-4). Another tactic is to copy legitimate prescriptions for multiple uses.47

Figure 1. Prescription altered to change the type of drug from Tylenol II to Tylenol IV

Figure 2. Prescription altered to change the number of refills from one to four

Figure 3. Prescription altered to change the quantity from 12 to 120

Figure 4. Prescription altered to add a drug (alprazolam)

Doctor shopping. Those who doctor shop often go to multiple doctors, emergency rooms, and pharmacies and feign symptoms or gain sympathy to obtain prescriptions. Common feigned ailments include migraine headaches, toothaches, cancer, psychiatric disorders, and attention deficit disorder.48 In addition, offenders may deliberately injure themselves to obtain a prescription from an emergency room. Other approaches include claiming to be from out of town and to have forgotten to pack prescription drugs,49 and claiming to have lost the drugs from a legitimate prescription.50 Given statistics on the number of prescriptions doctors write, doctor shopping may be the prescription fraud tactic with the highest success rate: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that the number of written prescriptions per office visit increased by 34 percent between 1985 and 2000 alone.51

Some legal sources of prescription medicines make it particularly easy for substance abusers and drug dealers to obtain prescription drugs. These pain clinics, or "pill mills," dispense prescription pain killers (often on a cash-only basis) and have lax restrictions on the volume that may be purchased.52 Pain clinics have been especially prominent in Florida, which historically has lacked regulation and a prescription monitoring program (although one was recently established), giving the state the dubious reputation of being called "the Oxy Express."53, †

† Florida recently tightened regulation of pain clinics, shut down those that served as drug pipelines, and plans to launch a prescription monitoring program (Alvarez 2011).

Calling in prescriptions. Prescription fraud in the form of impersonating medical staff and calling in false prescriptions poses the greatest challenge to identifying suspects. Typically, offenders call in a prescription when the doctor's office is closed, in case the pharmacist calls the office to confirm the prescription is legitimate; some offenders leave their own phone numbers for verification. Offenders are often patients or employees of the doctor they are impersonating, and they tend to act overly friendly to give the impression they regularly call in prescriptions.

Stealing blank prescription forms. Some offenders steal prescription pads from prescribers' offices‡ and write prescriptions for either themselves or fictitious patients. They may change the phone number so that they or an accomplice can answer verification calls.54

‡ Doctor's offices include physician's, veterinarian's, and dentist's offices.

Purchasing drugs on the Internet. Prescription drugs are readily available on the Internet.55 The anonymous nature of online purchases and potentially lax requirements regarding proof of doctors' prescriptions may lead offenders to acquire drugs through Internet sources. In an online search for commonly misused opioids, half of the results were websites that did not require a doctor's prescription.56 Indeed, some have observed that these websites have taken the doctor out of doctor shopping.57 However, survey research suggests that only a very small share of those who acquired prescription drugs illegally did so via the Internet.58 The National Survey on Drug Use and Health reports that fewer than 1 percent of those engaged in nonmedical prescription drug use in 2009 obtained those drugs through the Internet.59 One researcher concluded, "The assertion that the Internet has become a dangerous new avenue for the diversion of scheduled prescription opioid analgesics appears to be based on no empirical evidence and is largely incorrect."60

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Prescription Fraud

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.