Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

The Problem of Burglary of Single-Family Houses

This guide addresses the problem of burglary of single-family houses. It begins by describing the problem and reviewing risk factors. It then identifies a series of questions to help you analyze your local problem. Finally, it reviews responses to the problem, and what is known about them from evaluative research and police practice.

Reported U.S. burglaries have dropped dramatically in recent years, declining 32 percent since 1990. This drop is variably attributed to a robust economy, increased use of security devices, and cocaine users' tendency to commit robbery rather than burglary.1 With an estimated 1.4 million residential burglaries in 1999, the total number of reported burglaries is at its lowest since 1966.2 However, many residential burglaries—perhaps up to 50 percent—go unreported.3 † Despite the large decline in reported burglaries, burglary remains the second most common serious crime in the United States (just behind larceny-theft), accounting for 18 percent of all serious crime. Burglary accounts for about 13 percent of all recorded crime in the United Kingdom.4

† Burglaries with entry are more likely to be reported than are attempted burglaries. In Britain, about 75 percent of burglaries with entry are reported, compared with 45 percent of attempted burglaries (Budd 1999). Burglaries are also less likely to be reported when there is no loss, or relatively minor loss (Shover 1991). Kershaw et al(2001) [PDF] found that 75 percent of burglaries with loss were reported in Britain, while only 16 percent of burglaries with no loss were reported (Budd 1999).

The burglary clearance rate has remained consistently low, with an average of 14 percent in the United States and 23 percent in Britain. Rural agencies typically clear a slightly higher percentage of burglaries. The clearance rate for burglary is lower than that for any other serious offense. Indeed, most burglary investigations—about 65 percent—do not produce any information or evidence about the crime, making burglaries difficult to solve. Burglary causes substantial financial loss—since most property is never recovered—and serious psychological harm to the victims.5

To many, burglary is an intractable problem—difficult to solve, and one in which the police role primarily entails recording the crime and consoling the victims.6 Although burglaries have declined in recent years, police strategies such as Neighborhood Watch and target-hardening have had limited success in reducing these crimes. However, some quite specific, highly focused burglary prevention efforts show promise.

Related Problems

This guide focuses on burglary of single-family houses—primarily owner-occupied and detached. While there are many similarities between burglaries of these dwellings and those of multifamily homes, attached or semidetached houses, condominiums, and apartments (as well as other rental housing), the crime prevention techniques differ.† Single family detached houses are often attractive targets—with greater rewards—and more difficult to secure because they have multiple access points. Indeed, burglars are less likely to be seen entering larger houses that offer greater privacy. In general, greater accessibility to such houses presents opportunities to offenders.7

† Research does not always clearly describe the housing types crime prevention projects cover, or it combines types. While this guide focuses on single-family houses, promising practices for all types of residential burglaries have been examined.

In contrast to residents of other types of housing, private homeowners may use their own initiative to protect their property—and often have both the resources and incentive to do so. Residents of single-family houses do not depend on a landlord, who may have little financial incentive to secure a property. Most police offense reports include a premise code to help police distinguish single-family houses from other types of residences.

Although burglaries of multifamily homes are the most numerous, some studies demonstrate that single-family houses are at higher risk.8 National burglary averages tend to mask the prevalence of burglaries of single-family houses in suburban areas, where such housing is more common. The proportion of burglaries of single-family houses will vary from one jurisdiction to another, based on the jurisdiction's housing types, overall burglary rates, neighborhood homogeneity—especially economic homogeneity, proximity to offenders and other factors.

Other problems related to burglary of single-family houses not addressed directly in this guide include:

- Other types of residential burglaries, including those of apartments and other housing

- Commercial burglaries

- Drug markets and drug use

- Other offenses related to single-family houses, including larceny and assault.

Factors Contributing to Burglary of Single-Family Houses

Understanding the factors that contribute to your problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses.

Times When Burglaries Occur

Burglary does not typically reflect large seasonal variations, although in the United States, burglary rates are the highest in August, and the lowest in February. Seasonal variations reflect local factors, including the weather and how it affects occupancy, particularly of vacation homes. In warm climates and seasons, residents may leave windows and doors open, providing easy access, while storm windows9 or double-pane glass10 to protect against harsh weather provides a deterrent to burglary. The length of the days, the availability of activities that take families away from home, and the temperature may all have some effect on burglary.

In the United States, most residential burglaries—about 60 percent of reported offenses—occur in the daytime, when houses are unoccupied.11 This proportion reflects a marked change in recent decades: in 1961, about 16 percent of residential burglaries occurred in the daytime; by 1995, the proportion of daytime burglaries had risen to 40 percent.12 This change is generally attributed to the increase in women working outside the home during those decades—leaving houses vacant for much of the day. Thus, burglaries are often disproportionately concentrated on weekdays. The temporal pattern varies in Britain—about 56 percent of burglaries occur when it is dark.13

Exactly when a burglary has occurred is often difficult for victims or police to determine. Usually, victims suggest a time range during which the offense occurred. Some researchers have divided burglary times into four distinct categories: morning (7 a.m. to 11 a.m.), afternoon (12 p.m. to 5 p.m.), evening (5 p.m. to 10 p.m.), and night (10 p.m. to 7 a.m.). This scheme naturally reflects residents' presence at various times,† as well as offender patterns. Some research suggests that burglars most often strike on weekdays, from 10 a.m. to 11 a.m. and from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m.14—times when even routinely occupied houses may be empty.

† Some police reports may record only the earliest possible time of occurrence, the midpoint of a time range, the time of the report, or the shift during which the offense occurred. These varied recordings will influence analysis of burglaries' distribution across time (Waller and Okihiro 1978).

In many cases, determining the times when burglaries occur helps in developing crime prevention strategies and in identifying potential suspects. For example, burglaries by juveniles during school hours may suggest truancy problems. After-school burglaries may be related to the availability of alternative activities.

Target Selection

Burglars select targets based on a number of key factors, including the following:†

- Familiarity with the target, and convenience of the location

- Occupancy

- Visibility or surveillability

- Accessibility

- Vulnerability or security

- Potential rewards.

† These characteristics are also classified more generally as opportunity, risk, and rewards.

These elements interact. Visibility and accessibility are more important than vulnerability or security, which a burglar typically cannot assess from afar unless the resident has left the house visibly open.

Familiarity with the target, and convenience of the location. Offenders tend to commit crimes relatively close to where they live,15 although older, more professional burglars tend to be more mobile and travel farther.16 Burglars often target houses on routes from home to work, or on other routine travel routes. This tendency makes the following houses more vulnerable to burglary:

- Houses near a ready pool of offenders. These include houses near large youth populations, drug addicts, shopping centers, sports arenas, transit stations , and urban high-crime areas.17

- Houses near major thoroughfares. Heavy vehicle traffic that brings outsiders into an area may contribute to burglaries.18 Burglars become familiar with potential targets, and it is more difficult for residents to recognize strangers. Houses close to pedestrian paths are also more vulnerable to burglary.19

- Houses on the outskirts of neighborhoods. Like houses near major thoroughfares, those on the outskirts of neighborhoods have greater exposure to strangers. Strangers are more likely to be noticed by residents of houses well within neighborhood confines, where less traffic makes their presence stand out. Such houses include those on dead-end streets and cul-de-sacs—locations with few outlets.20

- Houses previously burglarized. Such houses have a much higher risk of being burglarized than those never burglarized, partly because the factors that make them vulnerable once, such as occupancy or location, are difficult to change. Compared with non-burglarized houses, those previously targeted are up to four times more likely to be burglarized; any subsequent burglary is most likely to occur within six weeks of the initial crime.21 There are a variety of reasons suggested for revictimization: some houses offer cues of a good payoff or easy access; burglars return to houses for property left behind during the initial burglary; or burglars tell others about desirable houses.22 Burglars may also return to a target months later, to steal property the owners have presumably replaced through insurance proceeds.23 Numerous studies show that revictimization is most concentrated in lower-income areas, where burglaries are the most numerous.24

- Houses near burglarized houses. Such houses face an increased risk of burglary after the neighbor is burglarized.25 Offenders may return to the area of a successful burglary and, if the previous target has been hardened, select another house, or they may seek similar property in a nearby house.

Occupancy. Most burglars do not target occupied houses, taking great care to avoid them. Some studies suggest burglars routinely ring doorbells to confirm residents' absence. How long residents are away from home is a strong predictor of the risk of burglary,26 which explains why single-parent, one-person and younger-occupant homes are more vulnerable. The following houses are at higher risk:

- Houses vacant for extended periods. Vacation or weekend homes, and those of residents away on vacation, are particularly at risk of burglary and revictimization.27 Signs of vacancy—such as open garage doors or accumulated mail—may indicate that no one is home.

- Houses routinely vacant during the day. Houses that appear occupied—with the lights on, a vehicle in the driveway, visible activity, or audible noises from within—are less likely to be burglarized.28 Even houses near occupied houses generally have a lower risk of burglary.29

- Houses of new residents. Neighborhoods with higher mobility—those with shorter-term residents—tend to have higher burglary rates, presumably because residents do not have well-established social networks.30

- Houses without dogs. A dog's presence is a close substitute for human occupancy, and most burglars avoid houses with dogs. Small dogs may bark and attract attention, and large dogs may pose a physical threat, as well.31 On average, burglarized houses are less likely to have dogs than are non-burglarized houses, suggesting that dog ownership is a substantial deterrent.32 (Security alarms, discussed below, are also a substitute for occupancy.)

Visibility or surveillability. The extent to which neighbors or passersby can see a house reflects its visibility or surveillability. A burglar's risk of being seen entering or leaving a property influences target selection, making the following houses more vulnerable to burglary:

- Houses with cover. For prospective burglars, cover includes trees and dense shrubs—especially evergreens—near doors and windows; walls and fences, especially privacy fences; and architectural features such as latticed porches or garages which project from the front of houses, obscuring front doors. Entrances hidden by solid fencing or mature vegetation—characteristic of many older homes are the entry point in the majority of burglaries of single-family houses.33

- Houses that are secluded. Secluded houses are isolated from view by being set back from the road, sited on large lots or next to nonresidential land, such as parks.34 Seclusion reduces the chance that neighbors or passersby will see or hear a burglar.

- Houses with poor lighting. For houses which are not secluded, poor lighting reduces a burglar's visibility to others. Steady lighting poses the threat that someone may be available to readily see the burglar, while motion-activated security lighting may serve as an alert in secluded areas. Lighting, of course, is not a factor in daytime burglaries, which are more common.

- Houses on corners.35 Because burglars can often more easily assess corner-house occupancy, and corner houses typically have fewer immediate neighbors, they are more vulnerable to burglary. Burglars may inconspicuously scope out prospective targets while stopped at corner traffic lights or stop signs.36

- Houses with concealing architectural designs. For privacy and aesthetics, some houses are designed and sited to be less visible to neighbors and passersby. Houses whose windows and doors face other houses appear to be less vulnerable to burglary.37

Accessibility. Accessibility determines how easily a burglar can enter a house. Thus, the following houses are at greater risk of burglary:

- Houses easily entered through side or back doors and windows.38 Side or back entries are the most common access point for burglars. In some areas, the front door is the most common break-in point, but this likely reflects architectural differences.39

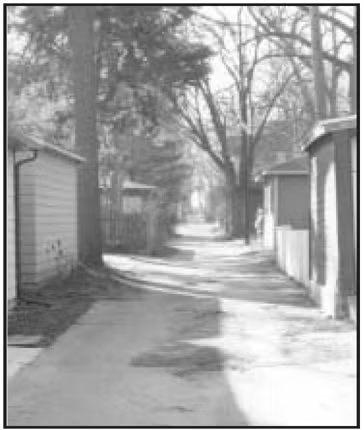

- Houses next to alleys. Alleys provide both access and escape for burglars, and limited visibility to neighbors. In addition, large side yards facilitate access to the backs of houses.

Vulnerability or security. How vulnerable or secure a house is determines how likely a burglar is to target it. The following houses are particularly at risk.

- Houses with weakened entry points. Poor building materials can make houses more vulnerable to burglary. Older houses may have rusting, easily compromised locks or worn and decaying window and door frames, while newer houses may be built with cheap materials.

- Houses whose residents are careless about security. Burglarized houses often have unlocked or open windows or doors.40 Seasonal variations may determine burglars' access methods—summer months allow entry through open windows or doors, while winter months bring an increase in forced entry.41

- Houses with few or no security devices. Studies show that alarms, combined with other security devices, reduce burglaries. Burglars are less likely to gain entry when a house has two or more security devices (including window locks, dead bolts, security lights, and alarms).42 Studies of offenders show that burglars may avoid houses with good locks, burglar bars or other security devices. By some accounts, burglars have already made the decision to burglarize a dwelling prior to encountering security features thus press ahead with the burglary. Experienced burglars may choose to tackle security devices,43 but the devices slow them down, making them more vulnerable to being seen.

Potential rewards. In selecting targets, burglars consider the size and condition of a house and the type of cars in the driveway as indicators of the type and value of the house's contents.44 Thus, the following houses are vulnerable to burglary:

- Houses displaying signs of wealth.45 Large and well-maintained houses with expensive vehicles are at risk of burglary. However, burglars avoid the most expensive houses, presumably because they assume those houses have more security or are more likely to be occupied.46

Goods Stolen

Burglars are most likely to steal cash and goods they can easily carry and sell, including jewelry, weapons, televisions, stereo equipment, and computers.47 They need transportation to move larger items, such as electronic equipment, while they often make off with cash and jewelry on foot.48

Few burglars keep the goods they steal. A study in Britain showed that burglars typically disposed of stolen property within 24 hours, usually after stashing it in a semipublic location. They thus minimized their risk by moving goods only short distances.49 They appeared to have few concerns about being arrested for selling stolen property, reporting they safely sold goods to strangers and pawnbrokers.50

Burglars tend to dispose of stolen goods through local pawnshops, taxi drivers and small-store owners.51 Few burglars use professional fences.52 Pawnshops—often outlets for stolen goods—have come under increasing scrutiny and regulation in many communities. Some burglars sell stolen goods on the street, occasionally trading them for drugs. Burglars commonly sell stolen goods in bars and gas stations;53 in bars, they usually sell the goods to staff, rather than customers.54 In many cases, burglars get little return for the goods.

Entry Methods

In about two-thirds of reported U.S. burglaries (including commercial ones), the offenders force entry. Unsecured windows and doors (including sliding glass doors) are common entry points. Burglars typically use simple tools such as screwdrivers or crowbars to pry open weak locks, windows and doors,55 or they may simply break a window or kick in a door.

In about one-third of burglaries, the offenders do not force entry; they enter through unlocked or open windows and doors, especially basement windows and exterior and interior garage doors.56 There is no consensus about the most common entry point—it depends on the house's architecture and siting on its lot.

Burglars

National arrest data indicate that most burglars are male—87 percent of those arrested in 1999.57 Sixty-three percent were under 25. Whites accounted for 69 percent of burglary arrests, and blacks accounted for 29 percent.

A lot of research has been conducted with burglars in the last decade, much of it to examine their decision-making, especially about target selection. Much of the research comes from interviews with offenders. Their willingness or ability to recall burglaries may influence the accuracy of the findings. Also, since police clear so few burglaries, there are likely major differences between successful burglars and those who get arrested. Successful burglars may be older or may differ in other important ways from those who get caught.

Burglars can be quite prolific: one study found that offenders commonly committed at least two burglaries per week.58 Some studies suggest there is great variability in the number of burglaries offenders commit.59

Burglars do not typically limit their offending to burglary; they participate in a wide range of property, violent and drug-related crime.60 Some burglars, however, appear to specialize in the crime for short periods.61 Burglars tend to be recidivists: once arrested and convicted, they have the highest rate of further arrests and convictions of all property offenders.62

Some research suggests that most burglaries involve more than one offender.63 But there is considerable variability in co-offending. In one jurisdiction, 36 percent of burglars acted alone, while in another, 75 percent did. One study revealed that in about 45 percent of residential burglaries, offenders had a partner.64 Young offenders are probably more likely to have one.

Most research categorizes burglars—as novice, middle-range and professional, for example. Novices, the most common type, tend to be younger, make minimal gains from burglaries, burglarize nearby dwellings, and can be easily deterred by dogs, alarms or locks. Professionals tend to be older, carry out bigger burglary jobs, willing to take on security devices, and are more mobile, scouting good targets farther from home.† Middle-range burglars fall somewhere between the two, and more often work alone than do the others. A key feature distinguishing the types of burglars is their outlet for stolen goods. Professionals tend to have well-established outlets, while novices must seek out markets for goods.

† Research suggests that the greater the financial loss due to a burglary, the less likely the police are to clear it (Poyner and Webb 1991 [PDF]), indicating that more skillful offenders commit the bigger burglaries.

Alternatively, some researchers categorize offenders as either being opportunistic or engaging in detailed planning65—a distinction useful for developing effective responses.

Research on burglars reveals the following characteristics:

- Most burglars are motivated by the need—sometimes desperate—to get quick cash,66 often for drugs or alcohol. Some offenders, particularly younger ones, are motivated by the thrill of the offense.67 A small number of burglars are motivated by revenge against someone such as an ex-girlfriend or employer.

- Studies suggest that drug and/or alcohol use and financial problems contribute to offending.68 Many burglars use their gains to finance partying, which may be characterized by frequent and heavy use of drugs and alcohol and a lack of regular employment.69

- Drug abuse, particularly heroin abuse, has been closely associated with burglary.70 In fact, some suggest the decline in U.S. burglaries during the 1990s was at least partly due to the rise in cocaine users and to their tendency to commit robbery rather than burglary.71 Heroin and marijuana users are more likely to be cautious in carrying out break-ins, while cocaine users may take more risks.72

- Burglars do not tend to think about the consequences of their actions, or they believe there is little chance of getting caught.73 Drug and alcohol abuse can impair their ability to assess consequences and risks.

- Burglars often know their victims,74 who may include casual acquaintances, neighborhood residents, people for whom they have provided a service (such as moving or gardening), or friends or relatives of close friends. Thus, offenders have some knowledge of their victims, such as of their daily routine.75

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online: Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email: [email protected]

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Burglary of Single-family Houses

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.