Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

Responses to the Problem of Gun Violence Among Serious Young Offenders

Your analysis of your local problem should give you a better understanding of the factors contributing to it. Once you have analyzed your local problem and established a baseline for measuring effectiveness, you should consider possible responses to address the problem.

The following response strategies provide a foundation of ideas for addressing your particular problem. These strategies are drawn from a variety of research studies and police reports. Several of these strategies may apply to your community's problem. It is critical that you tailor responses to local circumstances, and that you can justify each response based on reliable analysis. In most cases, an effective strategy will involve implementing several different responses. Law enforcement responses alone are seldom effective in reducing or solving the problem. Do not limit yourself to considering what police can do: give careful consideration to who else in your community shares responsibility for the problem and can help police better respond to it.

Recent evaluation research has revealed that police can prevent gun violence. While this guide categorizes police responses by whether they are primarily focused on offenders or on hot spots, in practice, they overlap. For example, when police focus on offenders in gangs, they sometimes also focus on gang turf and drug market areas. When police are deployed to prevent gun violence in particular places, they often focus on controlling the behavior of particularly dangerous offenders there. The distinction between the focuses matters less than the fact that police can prevent youth gun crime by strategically addressing identifiable risks.

The Richmond ( Calif.) Comprehensive Homicide Initiative demonstrates the benefits of an approach combining offender- and place-oriented responses.27 This problem-oriented policing project entailed a wide range of community-based and enforcement actions involving local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. Offender-oriented strategies included intensive investigations, the apprehension of violent fugitives, immediate responses to gang violence to prevent retaliation, and the strategic use of prevention and intervention programs. Place-oriented strategies included towing potential getaway cars in areas with high numbers of drive-by shootings, enforcing building codes at drug nuisance locations, and assigning officers to particular schools. An evaluation of this multifaceted program revealed that it significantly reduced homicides in Richmond, particularly those involving guns.28

Offender-Oriented Responses

A number of jurisdictions have been experimenting with new problem-oriented policing frameworks to prevent gang and group gun violence among serious young offenders. Pioneered in Boston, this approach is known as the "pulling levers" focused deterrence strategy. It was designed to influence the behavior, and the environment, of the groups of chronic offenders identified as being at the core of the city's gun violence problem. The pulling-levers approach attempted to prevent gang and group gun violence by making would-be offenders believe that severe consequences would follow such violence and change their behavior. A key element of the strategy was the delivery of a direct and explicit "retail deterrence" message to a relatively small target audience regarding what behavior would provoke a special response, and what that response would be.

Evaluation research has revealed the pulling-levers deterrence strategy to be effective in reducing gun violence among serious young offenders. The well-known Boston Gun Project/Operation Ceasefire intervention has been credited with a two-thirds reduction in youth homicides, and significant reductions in nonfatal gun violence.29 Subsequent replications of the Boston strategy have shown very promising results in reducing gun violence. An evaluation of the Indianapolis Violence Reduction Partnership revealed that homicides dropped by 42 percent, and that they were less likely to involve a firearm.30 Less scientifically rigorous assessments in Baltimore, Los Angeles, High Point, N.C., Winston-Salem, N.C., and Stockton reveal similar reductions in homicide and firearms violence.31

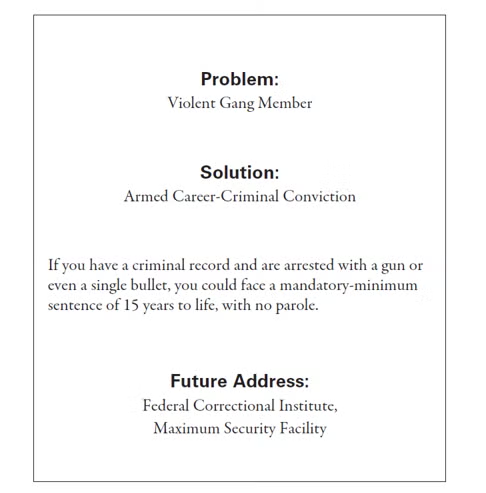

Some key elements of the "pulling levers" approach to prevent gun violence are also part of Richmond, Virginia's well-known Project Exile to deter convicted felons from illegally carrying guns. This program is essentially a firearms sentence-enhancement initiative, as offenders are diverted from state to federal courts. At the heart of the project, all Richmond felon-in-possession cases are prosecuted in federal courts, with the defendants' facing an average five-year prison sentence if convicted. The project also includes training for local police on federal statutes and search-and-seizure procedures, a public relations campaign to increase community involvement in fighting gun crime, and a massive publicity campaign to warn potential offenders about zero tolerance for gun crime and about the swift and certain federal sentence. Project advocates claim success based on a 40 percent decrease in Richmond gun homicides between 1997 and 1998. This claim has been disputed, however, as a recent evaluation found that the decrease would have likely occurred regardless of the project;32 the study suggests that nearly all of the decrease was probably attributable to an unusually high increase in and level of gun homicide before the project began. Nevertheless, it is important to note here that, as demonstrated in Boston, federal prosecution of gang-involved chronic offenders central to gun violence problems is an important component of an integrated violence reduction strategy.

General Requirements for a "Pulling Levers" Focused Deterrence Strategy

1. Enlisting community support. It is important for community members to think that police efforts to address youth gun violence are legitimate. Communities will not support any indiscriminate, highly aggressive crackdowns that put nonviolent youth at risk of being swept into the criminal justice system.† Before implementing a pulling-levers strategy, police need to engage community members in an ongoing conversation about legitimate and illegitimate means to control crime. The community needs to be aware that most of the gun violence problem is concentrated among groups of serious young offenders, and that police will be tightly focusing their activities on those youth (see text box below).

† See Response Guide No. 1 on The Benefits and Consequences of Police Crackdowns for further information.

Prosecutors can give priority to crimes committed by particularly dangerous offenders and work with police to develop solid cases. Federal law enforcement agencies can contribute the extra resources of the federal government and apply a wider range of stiff penalties for certain gun offenses. Social service providers should also have a role in the group, as the best way to change some offenders' behavior may be to offer them substance abuse counseling, job skills training, recreational opportunities, and the like (see text box below).

3. Placing responsibility on the working group. In most cities, no one agency is responsible for developing and implementing an overall strategy for reducing youth gun violence. Most police agencies have units or groups responsible for responding to incidents, but not for preventing incidents. The working group needs to be charged with preventing incidents to keep its focus on the bottom line of reducing youth gun violence.

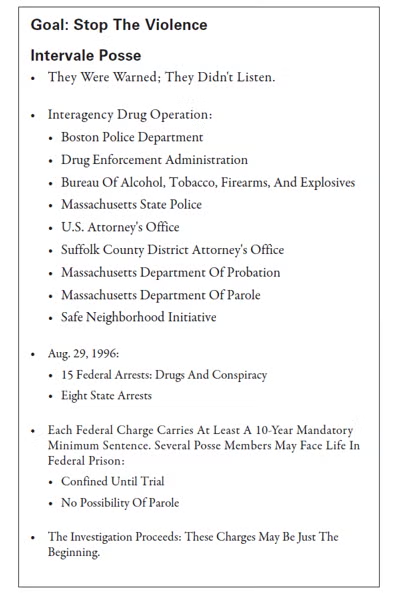

Figure 1. Anti-gang violence flier

Figure 2. Anti-gun violence flier

Key Elements of a "Pulling Levers" Focused Deterrence Strategy

6. Targeting intervention. Gangs and groups of serious young offenders select themselves for intervention by engaging in gun violence. The working group should focus on gangs and groups of chronic offenders currently engaged in gun violence rather than indiscriminately selecting or developing a "hit list" of gangs, groups, or particular individuals.

7. Sending the initial message. Working-group members must send a message to violent gang or group members that they are "under the microscope" because of their violent gun behavior. Police, probation, and parole officers should immediately increase their presence and activities in areas frequented by the targeted gang or group, and explain that their increased presence and activities are a response to gun violence. Social service agencies and community-based groups should also increase their presence and activities in the area, and explain to the target group or gang that they support police efforts to quell violence and will provide help to those who want it.

8. Pulling all available enforcement levers. The working group should identify a variety of possible enforcement actions. The group should tailor its approach to the targeted gang or group and assess different options, including conducting probation and parole checks, changing the community-release conditions for supervised offenders, serving warrants, giving special prosecutorial attention to any past or present crimes committed by gang or group members, enforcing disorder laws, and shutting down drug markets run by the gang or group. The key is to use the gang's or group's chronic offending against them, as it provides many opportunities for police to intervene. The goal is to save violent offenders from themselves rather than remove them from their environments. Police intervention should be harsh only to the extent necessary to stop gun offending. For some groups or particular individuals, changing probation conditions or shutting down a profitable drug market may be enough. For certain hardened offenders, heavy federal penalties may be necessary.

9. Continuing communication. It is critically important to demonstrate cause and effect to the targeted gang or group by directly and explicitly conveying the message. It should be very clear to the gang or group that the police are focusing on them because of their involvement in gun violence.†

† Police agencies should be creative in communicating with offenders. In Boston, face-to-face forums with violent gang members and working-group members were key in delivering the antiviolence message (Kennedy, Piehl, and Braga 1996a). In Minneapolis, working-group members visited gang-involved victims of gun violence—who were often in the company of their friends, in the hospital—and warned them against retaliation (Kennedy and Braga 1998). In Winston-Salem, North Carolina, older offenders were involving juvenile gun offenders in their criminal activities. In response, the Winston-Salem working group, while maintaining their focus on juvenile offenders, met with older offenders and explicitly warned them that involving juveniles in their illegal activity would result in focused police attention (Coleman et al. 1999).

10. Providing social services and opportunities. While law enforcement members of the working group are focusing on pulling the appropriate enforcement levers, social service providers and community-based groups should focus on diverting young offenders from their violent lifestyle. In the face of an impressive array of law enforcement actions, some gang or group members may want to take advantage of social services and other opportunities. This element of the approach allows the working group to provide some benefit to those who put down their guns.

Disarming Young Gun Offenders

11. Searching for and seizing juveniles' guns. The St. Louis Firearm Suppression Program (FSP) sought parental consent to search for and seize juveniles' guns.35 While this program did not explicitly focus on "dangerous" offenders, it aimed to prevent gun violence by disarming a very risky population of potential offenders—juveniles suspected of gang or gun involvement. The FSP was operated by the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department's Mobile Reserve Unit, a squad dedicated to responding to pockets of crime throughout St. Louis. Officers conducted home searches based on citizen requests for police service, reports from other police units, and information gained from other investigations. An innovative feature of the program was its use of a "Consent to Search and Seize" form to secure legal access to residences. Officers informed adult residents that the purpose of the program was to confiscate illegal firearms, particularly those owned by juveniles, without seeking prosecution. They told residents that they would not charge them with illegally possessing a firearm if they signed the consent form.36 While it was operating, the FSP generated few complaints from those subjected to searches, but received criticism from local representatives of the American Civil Liberties Union, who questioned whether residents could give real consent to search when standing face to face with police officers.

A key program component was to respond to problems identified by citizens, and the program's success depended on effective police-community relationships. By requesting community input regarding the gun confiscation process, the police department developed a model for policing gun violence that put a premium on effective communication and community trust not found in most policing projects. The FSP also was designed to send a clear message that the police and the community would not tolerate juvenile firearm possession because it threatened public safety. Unfortunately, while the program gained national attention for its innovative approach and seemed to be a very promising route to disarming juveniles,† the Mobile Reserve Unit underwent a series of changes that caused the program to be stopped and restarted several times; subsequent variations of the FSP did not use the same approach as the original one. Thus, a rigorous impact evaluation of the original FSP was not completed.

† Rosenfeld and Decker (1996) reported that, while the program was operating as originally designed, police seized 402 firearms in 1994, and another 104 firearms during the first quarter of 1995.

Place-Oriented Responses

In addition to focusing on high-risk individuals, police can prevent gun violence among serious young offenders by focusing on high-risk places at high-risk times. The Kansas City Gun Project,37 and its subsequent replications in Indianapolis38 and Pittsburgh,39 successfully used place-oriented policing responses to prevent gun crime in gun violence hot spots. In general, these studies examined the gun violence prevention effects of proactive patrol and intensive enforcement of firearms laws via safety frisks during traffic stops, plain-view searches and seizures, and searches incident to arrests on other charges. The Kansas City and Indianapolis studies also examined whether focusing police enforcement efforts at problem places simply displaced gun crime to different places or times. Neither study found any evidence of significant displacement.

It is important to note here that the research evidence is currently limited to place-oriented strategies involving mostly traditional police activities, such as increased patrol and street searches of suspicious individuals, at gun crime hot spots. While these interventions have produced crime control gains and have added to law enforcement's array of crime prevention tools, problem-oriented police should focus their efforts on those characteristics that cause a place to be a gun crime hot spot.40 Officers can reduce gun crime by changing the features, facilities, and management of problem places. For example, if problem analysis reveals that easy access to common areas in front of a high school causes youth gun crimes to be clustered there immediately upon school release, police should experiment with ways to limit access to these areas during problem times. The practice of problem-oriented policing is still developing, and additional research is needed on different approaches to controlling gun violence hot spots.

General Requirements for a Place-Oriented Enforcement Strategy

12. Enlisting community support. Some observers question the fairness and intrusiveness of aggressive law enforcement approaches and caution that street searches, especially of young minority males, look like police harassment.41 However, the results of the Kansas City and Indianapolis projects suggest that residents of communities suffering from high rates of gun violence welcome intensive police efforts against it. They strongly supported the intensive patrols and perceived an improvement in the quality of life in the targeted neighborhoods. Thus, the patrols apparently did not increase community tensions. The studies did not, however, assess the views of people stopped by police patrolling the hot spots. The police managers involved in these projects secured community support before and during the interventions through a series of meetings with community members. Effective police management (leadership, supervision, and maintenance of positive relationships with the community) seems to be the crucial factor in securing community support for aggressive, but respectful, policing.

13. Training officers in appropriate search-and-seizure techniques. In general, the gun hot-spot patrol teams initiated citizen contacts through traffic stops and "stop and talk" with people on foot. They used these contacts as an opportunity to solicit information and investigate suspicious activities associated with illegally carrying and using guns. When warranted for officer safety reasons (usually after people acted suspiciously), police conducted "Terry"† pat-downs for weapons; these searches sometimes escalated to more thorough checks when police had reasonable suspicion of criminal activity, and arrests were made. Officers participating in these programs must be trained in appropriate search-and-seizure techniques so that they conduct only legally warranted searches and seizures.‡ In addition, police supervisors should stress to their officers that they need to treat citizens with respect and explain the reasons for stops.

† In Terry v. Ohio (1968) 392 US 1, the Supreme Court upheld police officers' right to conduct brief threshold inquiries of suspicious persons when they have reason to believe that such persons may be armed and dangerous to the police and others. In practice, this threshold inquiry typically involves a safety frisk of the suspicious person.

‡ Beyond the landmark Terry decision, there are many court decisions that govern search-and-seizure techniques. For example, in Houghton v. Wyoming (1999) 526 US 295, the Supreme Court upheld police officers' right to search the belongings of the passengers of the car, incident to the arrest of any of the vehicle occupants. You should consult legal counsel regarding the application of search and seizure law in your jurisdiction.

Key Elements of a Place-Oriented Enforcement Strategy

14. Increasing gun seizures. The Kansas City Gun Project focused on testing the hypothesis that gun seizures and gun crimes would be inversely related. In other words, an increase in the number of guns seized in a targeted location would be associated with a decrease in gun crimes there. The evaluation revealed that proactive patrols focused on firearm recoveries resulted in a 65 percent increase in gun seizures and a 49 percent decrease in gun crimes in the target beat area.42 The authors concluded that removing guns from high-risk places at high-risk times caused the crime prevention gains.

15. Increasing contacts with potential gun offenders. The Indianapolis program tested the effects of two different types of directed patrol strategies on gun crime. In the north district, police focused on suspicious activities by particular people at high-risk locations. In the east district, police increased vehicle stops in the targeted area. During the intervention period, the number of firearms seized in the east district increased by 50 percent, while the north district experienced a modest 8 percent increase. The evaluation revealed that there were significant decreases in gun homicide, aggravated assault with a gun, armed robbery, and other gun crime in the north district. The east district had no significant changes in gun crime. In this study, the authors suggested that simply increasing gun seizures in a specific area does not seem to be enough to cause crime prevention gains. Rather, in Indianapolis, the effectiveness of this approach seems to depend on the ability of police to increase their visibility and contact with likely gun offenders within very small areas.43

Responses With Limited Effectiveness

16. Suppressing gangs without providing programs and services to address the social conditions that contribute to gang affiliation. The typical law enforcement suppression approach assumes that most street gangs are criminal associations that must be attacked through an efficient gang identification, tracking, and targeted enforcement strategy. The basic premise of this approach is that improved data collection systems and information coordination across different criminal justice agencies lead to more efficiency and to more gang members' being removed from the streets, quickly prosecuted, and given longer prison sentences.44 Typical suppression approaches have included street sweeps in which police officers round up hundreds of suspected gang members; special gang probation and parole measures that subject gang members to heightened surveillance levels and more stringent revocation rules; prosecution programs that target gang leaders and serious gang offenders; civil procedures that use gang membership to define arrest for conspiracy or unlawful associations; and school-based law enforcement programs that use surveillance and buy-bust operations.45 Unfortunately, gangs and gang problems usually remain in the wake of these intensive operations. Police agencies generally cannot "eliminate" all gangs in a gang-troubled jurisdiction, nor can they powerfully respond to all gang offending in such jurisdictions.46 Pledges to do so, though common, are simply not credible to gang members. Gang suppression programs' emphasis on selective enforcement may increase the cohesiveness of gang members—who often perceive such enforcement as unwarranted harassment—rather than cause them to withdraw from gang activity. Thus, suppression programs may have the perverse effect of strengthening gang solidarity.47

Free Bound Copies of the Problem Guides

You may order free bound copies in any of three ways:

Online:Department of Justice COPS Response Center

Email:askCopsRC@usdoj.gov

Phone: 800-421-6770 or 202-307-1480

Allow several days for delivery.

Email sent. Thank you.

Gun Violence Among Serious Young Offenders

Send an e-mail with a link to this guide.

* required

Error sending email. Please review your enteries below.

To *

Separate multiple addresses with commas (,)

- Your Name *

Your E-mail *

Copy me

Note: (200 character limit; no HTML)

Please limit your note to 200 characters.