Center for Problem-Oriented Policing

POP Center Home Problems Check and Card Fraud 2nd Ed. Page 1

Check and Card Fraud, 2nd Edition

Guide No. 21 (2020)

by Graeme R. Newman and Jessica Herbert

The Problem of Check and Card Fraud

This guide describes the problem of check and card fraud, and reviews factors that increase the risks of it. It then identifies a series of questions to help you analyze your local problem. Finally, it reviews responses to the problem, and what is known about them from evaluative research and police practice.

The guide covers fraud involving (1) all types of checks and (2) plastic cards, including debit, charge, credit, and “smart” cards. Each can involve a different payment method. While there are some obvious differences between check and card fraud, the limitations and opportunities for fraud and its prevention and control by local police are similar enough to warrant addressing them together. Furthermore, some cards (e.g., debit cards) are used and processed in a similar way to checks, and electronic checks are processed in a similar way to cards, so that the traditional distinction between cards and checks is fast eroding. Table 1 summarizes the essential differences between check and card fraud.

Table 1: Common Differences between Check and Card Fraud

| Check | Card | |

| Counterfeiting | Entry to intermediate level: requires photocopier or personal computer with standard color printer; printing clarity may vary with watermarks, special inks and other security features | Entry level: amateur alterations easily detectable; more advanced card alteration or production requires resources |

| Conversion to Cash | Can be converted to cash at checkout | Cannot be converted to cash at checkout (except for debit and phone cards) |

| Additional ID | Retail stores typically require additional ID; banks require ID and may ask for additional security (e.g., fingerprint) measures | Additional ID rarely requested |

| Signature Checking | Signature rarely checked, unless check-cashing card required | Signature present on card is primary means of verifying card user, not always verified with additional ID |

| Payment Processing | Merchant submits check to bank for payment | (Highly simplified): merchant submits card charge to bank, which submits payment request to card issuer, which verifies payment to merchant’s bank, which then pays merchant |

| Loss Liability | If bank rejects payment, merchant carries loss and must recoup it from customer; legitimate account owner may be liable, depending on bank policy | Negotiable: merchant may incur loss, or card issuer may agree to do so; legitimate card owner generally protected from loss |

| Vulnerability Points | Check acquisition; check payment and cashing; check processing; and bank, business, and consumer environments | Card issuance; card acquisition; checkout; card-not-present sales (usually telephone or online sales); and after the sale (product returns) |

| Organized Crime | Less common with checks, though sophisticated check- counterfeiting rings do exist | Counterfeiting and distribution of credit cards widely adopted by organized crime groups |

In 2009, financial theft researchers reported a 22% increase in financial fraud crimes from the previous year, affecting approximately 9.9 million Americans.[1] Costing consumers an estimated $50 billion annually, the complexities of keeping information secure in a digital world has prevented law enforcement and private businesses from getting a grasp of fraud offenses.[2]

The increase of mobile banking has contributed to this increase of offenses. For check fraud, the increased use of remote deposit capture (RDC) increases vulnerabilities for financial institutions by allowing instantaneous transactions. Financial institutions reported a 400% increase of check fraud through RDC from 2012 to 2014.[3]

For card theft specifically, approximately 40% of victims of financial loss due to fraud reported in 2014 knowing how their personal information or cards were compromised.[4] This is consistent with other fraudulent reporting by researchers and private businesses that approximately 70% of identity theft resulting in financial losses occurs by insiders (e.g., persons with legal access to identifying information).[5] The volume and variety of scams to obtain a person’s financial information (e.g., phishing, charity scams) further perpetuates the collections and exploitation of financial accounts.

Apart from the obvious financial loss caused by check and card fraud, it is a serious crime that requires preventive action. It affects multiple victims and significantly contributes to other types of crime. At an elementary level, fraud is easy to commit, and the chances of apprehension and punishment are slight.† Thus check and card fraud is an ideal entry-level crime from which people may graduate to more serious offenses. Other crimes that either feed off check and card fraud or facilitate its commission include the following:

- Drug trafficking. Addicts forge checks or fraudulently use credit cards (often bought cheaply as “second string” cards—that is, stolen or counterfeit cards that have already been used). So the fraud fuels the drug trade.[6]

- Identity theft. There is increasing evidence to suggest that obtaining or accessing credit card or bank accounts are the main motive for identity theft.‡ In 2014, the Bureau of Justice Statistics identified over 15 million persons victimized by identity theft, with a mean loss of $1,090 per event.[7] A majority of these events – 86 percent – were for existing credit or bank cards. Although technology has made the counterfeiting of checks and plastic cards much more difficult over the last decade, the access to tools to recreate these payment mechanism is readily available through online purchasing and in-home printers.

- Mail fraud. Offenders intercept checks, credit cards, or bankcards in the mail, or do not forward mail that card issuers or banks send to a customer’s old address.

- Burglaries, robberies, and thefts from cars. Offenders may commit these crimes specifically to get plastic cards, or they may get them as a by-product of the crime.§

- Pickpocketing. Pickpockets may be attracted to shopping malls and other crowded venues where people use checks and cards.

- Fencing. In areas where offenders commit check and card fraud to buy high-priced goods, a fencing operation may arise to facilitate conversion of the goods into cash. Online vendors that offer cash outs for store cards or reloadable cards further assist for cash conversions.

- Cyber-theft. Customer databases that include credit card and other personal information are very valuable to cyber hackers. They have therefore become targets for hackers. Cyberattacks for financial information has turned to be a costly crime for financial industries and businesses. The loss of personal and financial information from Target, Home Depot, Aetna and the federal Office of Personnel Management has been estimated over $450 million in loss protections, network defense mitigation and insurances.[8]

- Extortion. The permeation of Internet use by individuals has increased victimization through extortion or ransomware techniques. Under the guise that personal information is being kept locked until payment is provided, cyber-thieves willing receive financial information and personal details from victims to “release” information.[9]

- Organized crime. Counterfeiting and marketing cards requires little costs, for both production and distribution, and midlevel organization among rings of offenders to execute fraudulent activities. There are two groups that operate here: 1) Organized hacking rings that procure personal and/or financial information and sell this information for profit and 2) Organized theft rings, or carders, who use this information to produce counterfeit cards and fraudulent transactions in either physical or virtual sales in retail stores, or within ATM and bank transactions. These organized rings vary by region of the world[10], although the United States hosts a significant number of carding organized rings.[11] In 2013, eight offenders were charged in New York with stealing $45 million from banks through the use of fraudulent ATM cards.[12] In 2014, a Georgia man was one of six persons indicted for $50 million theft from stolen credit card data.[13]

- Local gang-related crime. Small gangs may feed the needs of addicts and the poor by using second-string cards to buy food and other items at supermarkets. The locals may protect these gangs, because they provide a “service” to the community.

- Cons and scams.[14] The Internet now carries a wide range of cons and scams offenders use to get credit card and other personal information from unknowing victims. People can easily create false websites and storefronts, as little skill is required to do so. Phishing scams and corporate email takeovers are key cyber techniques that solicit personal and financial information from unsuspecting victims. Furthermore, many websites offer information on setting up such websites and on running scams.

- Financial crimes against the elderly. The elderly are prime targets of cons and scams, including check and credit card fraud. (For more information, see the Problem-Specific Guide on Financial Crimes Against the Elderly.)

- Shoplifting. Committing check and card fraud is simply another way of “lifting” products from retailers. Using a credit card fraudulently at checkout is much less risky (because the authentication methods are so cursory).[15] Point of sale fraud accounted for approximately $6 billion in losses from retail stores in 2014.[16]

- Car theft. Car rental companies are prime targets for credit card fraud. Offenders may sell fraudulently rented cars in the stolen vehicles market.

† In a Montreal study, the success rate with a totally counterfeit card was 87 percent, and with an altered card, 77 percent. At checkout, the average success rate was 45 percent, although in most of the cases where the sales clerk rejected the card, the offender simply walked away, without being accosted (Mativat and Tremblay 1997).

‡ In 2002, the Federal Trade Commission reported that the main motives for identity theft were as follows:

To obtain/take over a credit card account............................. 53%

To acquire telecommunications services............................... 27%

To obtain/take over a checking account................................ 17%

Other............................................................................................. 3%

§ Thefts from cars may increase as a way to get credit card and personal information if other opportunities to get such information are blocked by improved security measures in the manufacture and processing of plastic cards and checks (Levi 1998). However, in other studies, this “displacement” does not always occur, even within card fraud itself—for example, from using stolen credit cards to counterfeiting cards (Mativat and Tremblay 1997).

Plastic-card technology has continued to evolve. Issuers now offer both debit and credit services on one card, with all cards having encrypted chip technology, requiring a personal identification number (PIN) for each transaction. Paperless or electronic checks are increasingly used in business-to-business transactions, as well as monthly payments for individual expenses (e.g., rent or mortgage, car payments). Criminal use of these different products involves a wide range of skills, activities, and financial investment. The type of fraud will depend on the points of vulnerability targeted in the delivery of services, as outlined in Table 1.

In general, check and card fraud may be divided into two activities: the illegal acquisition of checks and cards, and the illegal use of checks and cards. This distinction is not absolute, since offenders may gain access to some cards (e.g., debit cards) without actually acquiring the cards (e.g., by stealing account numbers).

Illegal Acquisition of Checks and Cards

The following are some of the ways offenders illegally acquire checks and cards:

- Altering checks and cards. Offenders can do so with the simplest equipment. However, altered checks and cards are sometimes easy to detect.

- Counterfeiting checks and cards. Reasonably priced machines for embossing, encoding, and applying holograms to cards are available on the Internet.

- Committing application fraud. Offenders get a checking or credit card account by using another person’s identity or a fictitious one.

- Stealing checks and cards through muggings, pickpocketing, theft from cars, and burglaries.†

- Intercepting checks and cards in the mail. Intercepted cards are particularly desirable because they are unsigned. Offenders may also intercept boxes of blank checks.

- Getting another person’s PIN through trickery, for example, by “shimming” (watching as the person punches in a PIN). PINs can also be obtained through placement of cameras near ATMs or other point-of-sale devices to capture images during transactions. This is common in ATM skimming operations.

- Manufacturing and marketing counterfeit cards via internationally organized crime rings.

- Renting or selling stolen or counterfeit cards to a group of “steady customers” via locally organized crime rings.

- Hacking into a retailer’s customer database to get credit card numbers.

- Setting up bogus websites, either in spoofing or ransomware techniques, that request credit card and other personal information.

Illegal Use of Checks and Cards

The following are some of the ways offenders illegally use checks and cards:

- Presenting a bogus check or card at checkout. The sales clerk is supposed to verify that (a) the check or card represents an actual account (usually done by checking a computer database), and (b) the person presenting the check or card is the account holder. If the offender gets away with using the check or card, he or she may then dispose of the goods by (a) selling them through a known fencing operation or informally in local businesses, or (b) returning the goods to the same store (or a different branch of the store) for cash.

- Making a “card-not-present” purchase (by telephone or on the Internet). Offenders avoid the scrutiny of sales clerks or security cameras and need only the card information, not the card itself. Card-not-present fraud is a major contributor to overall card fraud (see Figure 1). Between 1999 and 2001, it increased some 130 percent in the United Kingdom, with similar increases internationally.[17]

- Denying ordering and/or receiving an item. Customers who order an item online using a legitimate credit card may deny doing so, claim they never received the item, and stop payment on the card. Or they may claim that an item they did order was never delivered, and demand a refund.

- Targeting a particular store or set of stores. Small bands of career fraudsters may work together to “hit” a particular store or set of stores with stolen or counterfeit cards. These bands usually do not target stores in or near their own neighborhoods; rather, they will travel some 50 miles to other shopping areas to commit fraud.[18]

- Targeting ATMs for cash withdrawals. Counterfeit cards can be used for routine cash withdrawals, sometimes moving to several ATMs to maximize amount of withdrawal.‡ More sophisticated theft rings may adapt the information on the magnetic strip, which affects the operating system of the ATM and may allow for unlimited cash to be withdrawn from corresponding accounts.

† Levi (1998) has noted that one in five street robbers in London obtain credit or debit cards from their victims.

‡ Although banks have limits on daily cash withdrawals, the use of multiple cards/accounts make ATM cash thefts attractive to many organized rings.

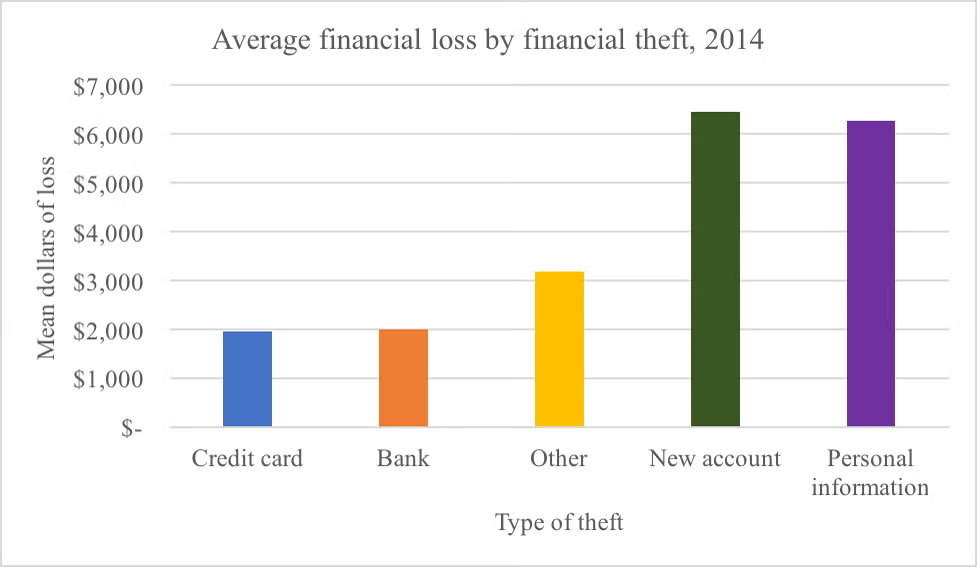

Figure 1. Average financial loss by theft type, 2014[19]

Low Reporting of Check and Card Fraud

Perhaps the biggest problem for police is that people rarely report check and card fraud to them.§ In one recent study, only one in four incidents of check and card fraud were reported to the police.[20] It is very likely that you have a check or card fraud problem in your area, but do not know about it. Many credit card issuers promise zero loss to the user if the card is lost or stolen and illegal are charges made. Thus, if cardholders do not suffer financially, they may have less motivation to report the offense to the police. With the increase of offenses, and the fear of being victimized again by account holders with fraudulent claims, banking institutions commonly request for victims of card fraud to file a report with local police. Some police departments capture these reports as a courtesy report for insurance purposes, rather than criminal events, which may minimize departmental awareness of fraud trends. Merchants are also reluctant to report fraud, or even to use fraud prevention techniques at checkout, for fear that it will slow down the purchasing process and negatively affect sales or reputation.[21] Thus, fraudsters think their chances of getting caught are very slim. One study reported that some 80 percent of respondents thought it was easy or very easy to carry out credit card fraud.[22]

§ Over 90 percent of people report their lost or stolen card to the card issuer within one day. They rarely, however, report their loss to the police, unless it results from a crime such as pickpocketing, burglary, or mugging (Levi and Handley 1998a).

The situation with check fraud is slightly different. Some banks hold the account holder liable for loss. The merchant who accepts the check may also be held responsible, since the bank simply refuses to honor the check if it detects a forgery. (Thus, retailers—especially North American supermarkets, where check cashing is a common service—are often more willing to cooperate with police or develop their own security procedures concerning check fraud.) It is not uncommon for some conflict to arise between merchants and banks as to who should bear the loss.[23] This is a serious problem because, as we will see, cooperation among competing merchants and between merchants and banks is central to preventing and reducing check and card fraud.[24]

Banks, some retail stores, and supermarket chains commonly prefer to deal with merchandise loss, employee theft, shoplifting, and check and card fraud internally.[25] There are three significant reasons for this preference:

- They do not think police have the specific skills, knowledge, and experience needed to deal with security issues in the banking and retail environment.

- They hold a widespread view that losses due to theft and fraud are simply a cost of doing business, and that those losses are more than offset by the profits made from using tempting product displays or only quickly checking customer identities at checkout.

- They fear that calling in the police might negatively affect business, because the crime problems become public.

The check and card fraud that businesses do report to the police is usually committed by repeat or “professional” fraudsters. Or, for whatever reasons, the in-house security wants to transfer responsibility to the criminal justice system.

Factors Contributing to Check and Card Fraud

Understanding the factors that contribute to your problem will help you frame your own local analysis questions, determine good effectiveness measures, recognize key intervention points, and select appropriate responses. You should be aware that a majority of check and card fraud is due to factors beyond police control. Such factors include the following:

- Police typically do not have access to the vulnerability points in the complex transactions that make up check and card processing.

- It is inherently difficult to verify a check or card user’s identity.

- The Internet has greatly increased the opportunities for fraud, perhaps having its greatest impact through fraudulent card-not-present sales (see Figure 1).†

- Information about counterfeiting, skimming, and hacking is now widely available on the Internet. Thus, it is easier to commit card fraud than ever before.[26]

- To some extent, the sheer volume of card use accounts for the increased amount of card fraud. In the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, debit and credit card use has increased tremendously over the last 20 years. These differences are largely related to the structure of financial service markets in the various countries.

- The amount of card fraud committed internationally has substantially increased in recent years. While the implementation of EMV technologies in Europe around 2004 slowed point-of-sale card fraud, the influx of online shopping and transactions has made consumers vulnerable through computer hacking techniques which obtain financial and personally identifying information. The United States move to EMV technologies for both credit and debit cards may impact point of sale, but the online sales are likely to still be vulnerable.

- Although the rate of check fraud has decreased considerably in the past decade, the financial loss due to check fraud continues to increase, simply because of the increase in the volume of sales.

- There is a technological “arms race.”[27] Each technological advance makes it harder and harder to counterfeit checks and cards. Microdot printing on checks, hidden markings on checks and cards that show up on color photocopiers, holograms, magnetic strips, and now embedded chips—all these and many more advances have raised the level of skill and equipment needed for fraudsters to counterfeit checks and cards. Unfortunately, dedicated fraudsters quickly acquire the skills and equipment, so are soon able to produce checks and cards that are extremely difficult to identify as counterfeit.

- International organized crime groups that specialize in counterfeit credit cards generally lie beyond the reach of local police, although their markets certainly lie within local neighborhoods. Some groups became very active in Southeast Asia toward the end of the 1990s, and in a short time, have managed to overcome every new security feature introduced into plastic-card manufacture. Their distribution system employs Asians in large North American and European cities.[28] Other groups stem from South America and Russian, primarily due to computer hacking skills aimed at the exfiltration of personal and financial information. The organized groups recruit “droppers”, complicit criminals, or unsuspecting persons to assist in the sale of fraudulently purchased goods in order to gain cash.

- Many card issuers are eager to get customers. In recent years, the competition has become very intense. The mail and Internet are loaded with tempting offers, and it is now very easy to get a credit card.

- Many card issuers do not hold cardholders responsible for any loss incurred through fraudulent use by another. Thus, cardholders have no real motivation to take security precautions. In fact, they may even collude with others. Retailers may bear the loss in card-not-present sales, and card issuers in standard credit-card sales. This has shifted as the rate of card fraud has increased with technological access to fraudulent purchases. Card issuers have agreed to implement high security at point-of-sale (e.g., EMV technology, PIN requirements) to decrease the amount of loss incurred.

Although police face these and other obstacles when addressing check and card fraud, there is much that can be done.

† A traditional credit card purchase goes something like this: At checkout, the customer gives the card to the sales clerk, who runs it through the computer to check whether the account is legitimate. The clerk then checks whether the customer is the person named on the card (usually by comparing signatures, which are not an especially reliable form of identification, by the way). In a face-to-face situation, the clerk can try to verify the customer’s identity. However, with telephone and online purchases, there is no direct way to do so.